I recently found out that the blog I’d posted this on (Popular Romance Project) has been wiped from the internet, causing a dead link on my website. So I’m reposting it here to preserve it.

One of the topics that comes up a lot among historical writers is what research books are essential. If you ask your top ten favorite authors, you’d probably end up with a pretty impressive research library (and I’d LOVE to see other authors tell us about their Must Have Books in the comments). Here are mine. I think these books are must reads for anyone wanting to create an authentic Georgian/Regency world, and I’m going to talk a little bit about why.

The Rise of the Egalitarian Family: Aristocratic Kinship and Domestic Relations in Eighteenth-Century England by Randolph Trumbach (1978; ISBN 0127012508; OOP, used ~$40).

When writing a love story, you need to understand the mores of the times. One of the many, many useful things that Trumbach does in this book is discuss the evolution of the love match as a social ideal in the Georgian period. It’s all bound up with the Enlightenment and the Hardwicke Marriage Act and the slow descent of the nobility’s dependence on land for their fortunes. By the Regency period, Trumbach maintains that the love match had ousted the arranged marriage entirely and was well on its way to trumping matches based on social advantage and monetary considerations. So if you want to have that tension between generations, this book is a great resource for understanding where everyone might be coming from in their viewpoint of what would be ideal.

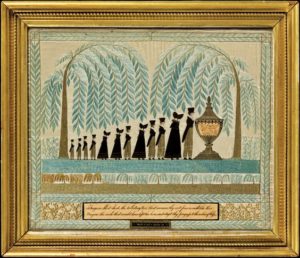

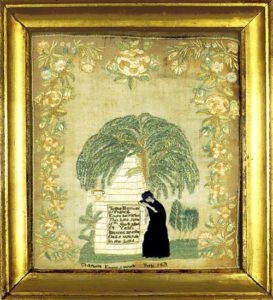

This book is also the main source for basic information that we use in every book, such as the time periods for mourning, marriage settlements, consanguinity. And it features tons of information about basic domestic issues such as the role of wives in the family and the raising of children. Really, it’s just an all-round great book for getting a solid understanding of what was going on inside people’s everyday lives.

The Regency Companion by Sharon Laudermilk and Teresa Hamlin (1989; ISBN 0824022491; OOP, used ~$200, use interlibrary loan).

This is just an all-round brilliant book. It contains a wealth of information about everything from the Season and courtship among the ton to basics about how people lived such as the clubs men frequented, the theatres, roles of servants, etc. I just don’t know any other book that provides the information this one contains. It’s essentially foundational.

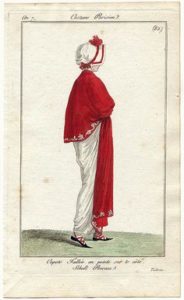

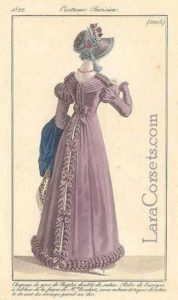

20,000 Years of Fashion by Francois Boucher (1973; ISBN 0810900564: OOP, used ~$12).

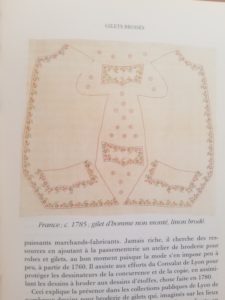

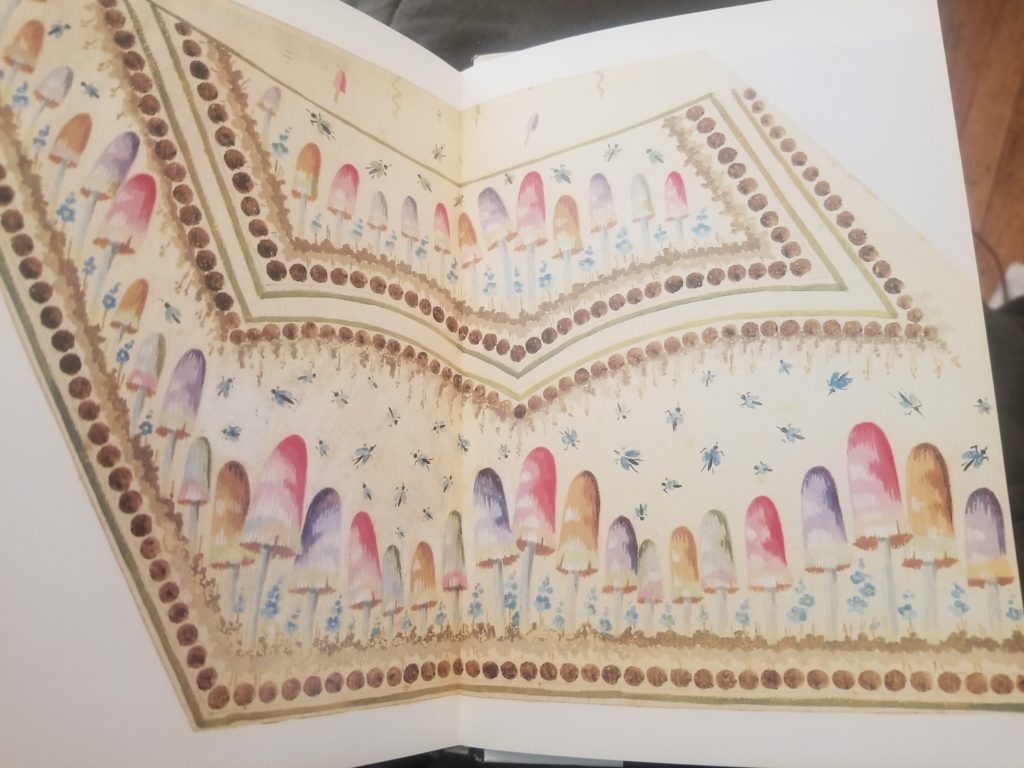

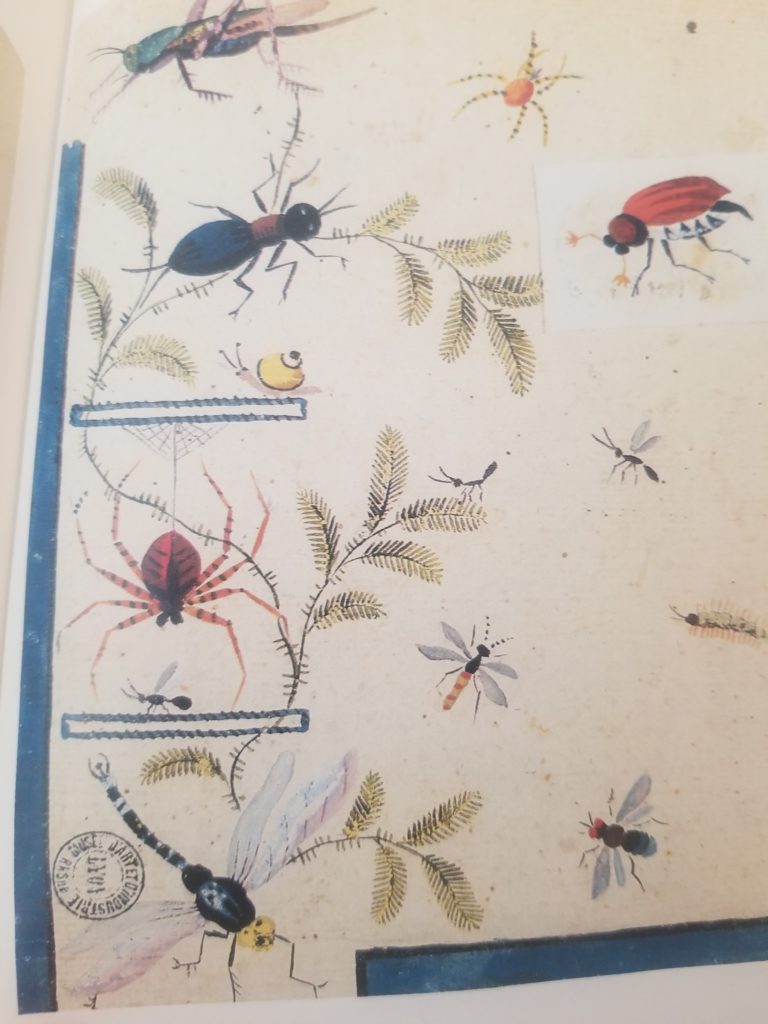

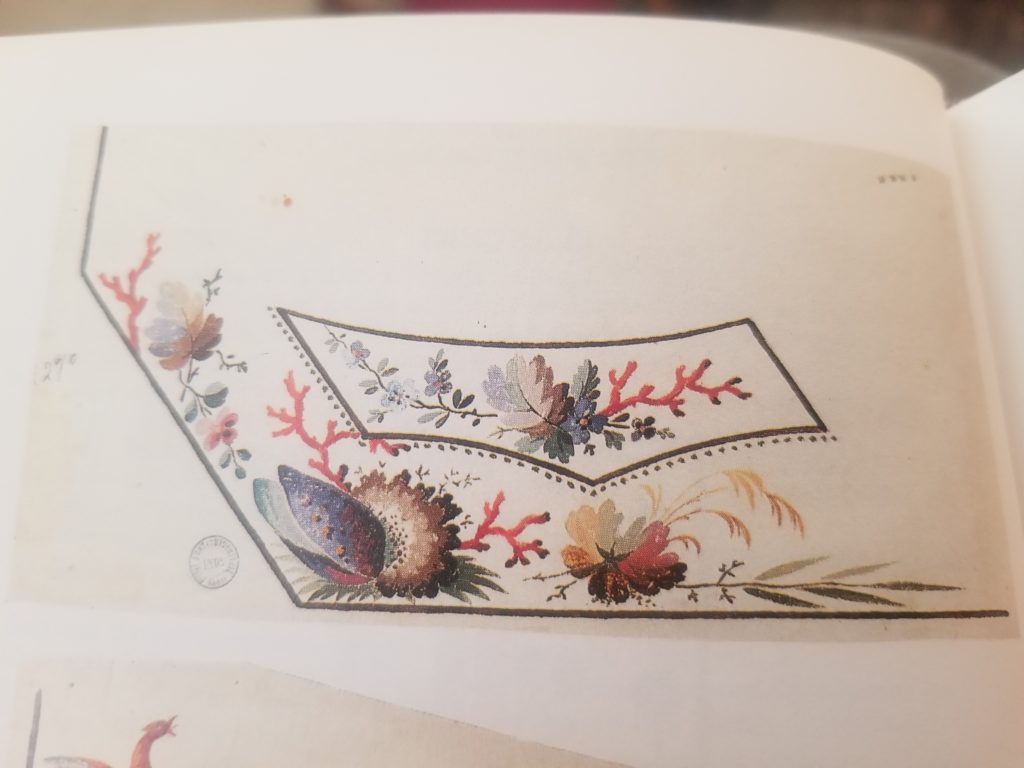

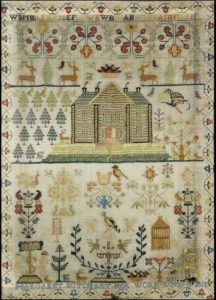

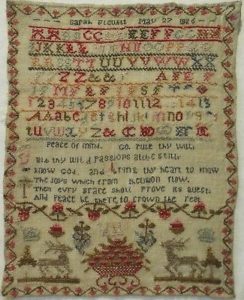

I simply don’t know a better survey book for fashion. While I’m obsessed with clothing, I don’t think everyone else needs to be, nor do I think it’s a wise place to spend your time considering, “With a small bit of effort, he undid her gown and it fell to the floor” suffices to get you where you need to be. But I do think every writer needs to know enough not to make any glaring errors, and Boucher’s summaries and careful selection of images are perfect for providing that little bit of knowledge you need (and since it covers pretty much all of European history, you don’t need to buy a new book if you decide you’d rather write Victorian settings, or Medievals.

The Family, Sex, and Marriage in England 1500-1800 by Lawrence Stone (1983; ISBN 0061319791: OOP, used ~$1).

Stone not only delves into the basic makeup of the English family (and he mostly talks about the upper class, “Barons and up” as he labels them), but he has great charts that provide vital information regarding the average ages at which people in this class married, how many times they were married, under what circumstances they were likely–and unlikely–to remarry, etc. This book provides a sort of grounding for the history of your characters’ families and a general understanding of how the most basic building block of society evolved and functioned. I would also suggest his Road To Divorce to anyone who wants to write about characters with broken marriages.

The British Aristocracy by Mark Bence-Jones (1979; ISBN 0094617805; OOP, used ~$10).

I love this book! It’s extremely insightful about how the aristocracy think of themselves, what matters to them, and what the origins of those feelings are. Bence-Jones is an insider who lays it all out for us. I found the section on “The Concept of the Gentleman” extremely enlightening and also highly recommend it for the chapter on “The Aristocratic Character.”

The Art of cookery Made Plain and Easy by Hannah Glasse (1774; free on Google Books)

Though you might throw food in with the unimportant minutia, I think that’s a mistake. The devil of historic world building really is in the details, and nothing throws a well-informed reader like potatoes in a Medieval setting or iced tea in a Regency (or indeed in any book set in England, including a contemporary!). And this isn’t something you have to spend years studying to get a handle on. Glasse’s historic cookbook is free on Google Books and contains hundreds of period recipes. Plus, it adds depth to get little things like this right, and it’s fun to have you characters eat Maids of Honor rather than just lemon cheesecakes (and it’s good to know that period “cheesecake” is pretty much a modern cheese Danish too).

Peerage Law in England by Sir Francis Beaufort Palmer (1907; free on Google Books)

This is a basic guide to how peerages are inherited, disputed, and granted, with many examples laid out so you can really understand it. This knowledge is ESSENTIAL if you want to deal with tricky inheritances. Yes, it’s a very dry book, but you really can’t hope to just muddle your way though these issues. Basic questions that this book answers come up on my historical writers’ loop all the time (the most common one is usually about a peer losing his title if it’s proven that he’s illegitimate, which simply can’t happen; all challenges have to be made BEFORE the title is granted, during the review of the claim).