Two hundred and one years ago on June 24, 1812, Napoleon began his invasion of Russia.

Tsar Alexander had angered Napoleon by ceasing to continue the blockade against British goods which was ruining the Russian economy. So, to teach the Tsar a lesson, Napoleon amassed an army of 450,000 men to march into Russia. Napoleon was convinced the whole affair would be finished in 20 days and that the Tsar would capitulate, but if ever weather changed the course of history, it was during this campaign. Weather and the fortitude of the Russian people.

Tsar Alexander had angered Napoleon by ceasing to continue the blockade against British goods which was ruining the Russian economy. So, to teach the Tsar a lesson, Napoleon amassed an army of 450,000 men to march into Russia. Napoleon was convinced the whole affair would be finished in 20 days and that the Tsar would capitulate, but if ever weather changed the course of history, it was during this campaign. Weather and the fortitude of the Russian people.

As the French army marched into Russia, the Russian army refused to give them any true engagement. Instead they retreated, burning the countryside behind them. Because Napoleon’s armies replenished their supplies through pillage and plunder, the burning of crops denied the soldiers sustenance.

On June 27, Napoleon conquered Vilna with barely a fight, but that very night a huge electrical storm killed many troops and horses, with freezing rain, hail, and sleet. Later the oppressive heat would kill more troops. Others would desert looking for food and plunder

It was September before the first major battle was fought at Borodino. By then Napoleon had already lost 150,000 soldiers to exhaustion, sickness, or desertion. The Battle of Borodino was an extremely bloody one with total casualties on both sides of 70,000. The Russians withdrew and Napoleon marched triumphantly on to Moscow.

Except the Russians burned Moscow and its stores, leaving only hard liquor. Most of its citizens had fled. Napoleon, nonetheless, waited three weeks in Moscow, expecting the Tsar to request negotiation.

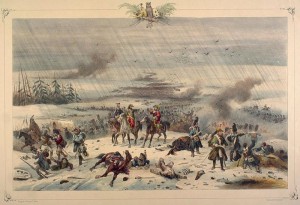

Instead it started to snow and Napoleon realized he and his army could not survive a Russian winter. He ordered the retreat but the Russians blocked his chosen route, forcing his army to retreat over the already burned and barren land from which they had come. The winter came early and was particularly harsh, with high winds, snow, and sub-zero temperatures. Thousands more died of exposure. It was said that soldiers split open dead animals and crawled inside for warmth or stacked dead bodies for insulation.

Instead it started to snow and Napoleon realized he and his army could not survive a Russian winter. He ordered the retreat but the Russians blocked his chosen route, forcing his army to retreat over the already burned and barren land from which they had come. The winter came early and was particularly harsh, with high winds, snow, and sub-zero temperatures. Thousands more died of exposure. It was said that soldiers split open dead animals and crawled inside for warmth or stacked dead bodies for insulation.

By the time in late November when the Grande Armée crossed the frigid Berezina River, its numbers were depleted to 27,000 from that original 450,000.

Still, Napoleon stated it was a victory.

Instead it turned the tide of Napoleon’s perceived invincibility. Prussia, Austria, and Sweden rejoined Russia and Great Britain against Napoleon. Although he was still able to raise an army to continue the fight against them, it was never the fighting force it once had been.

Three times in History armies tried to invade Russia only to have their efforts further their demise. Napoleon tried it in 1812; Charles XII of Sweden tried it in 1708; Hitler tried it in 1941. For each the Russian winter and the scorched earth policy took a horrific toll.

The Weather Channel will be airing a new series, Weather That Changed the World. “Russia’s Secret Weapon” to be aired June 30 at 9 pm, will be about the disastrous winter that changed Napoleon’s fate.

Do you have an example of when weather changed the world?