Today the news will be filled with weather reports, as we in the US discover if Tropical Storm Isaac turns into a hurricane and if it will hit New Orleans and the Gulf Coast, where Katrina did such devastating damage in 2005.

For my blog today, I went looking for extreme weather during the Regency period. And I found it! What amazing synchronicity.

Almost 198 years to this day, a storm figured in the burning of Washington, D.C. during the War of 1812.

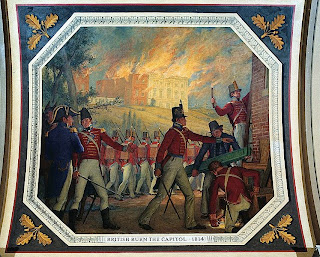

On August 19, 1814, British warships sailed up the Patuxent River. The British army disembarked in Maryland and defeated the American forces at the Battle of Bladensburg. The British marched on to Washington, D.C. on August 24, while government officials and residents fled the city, including, at the last minute, the First Lady, Dolley Madison, who rescued the Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington.

Unfortunately for the British, there were no representatives of government left in the nation’s capitol to surrender, so, after eating a dinner meant for Dolley Madison’s party in the White House, the British admiral gave the order to burn the public buildings of the city. The White House and Capitol were still burning on August 25 when a severe thunderstorm struck. It is thought that a tornado tore through the city, catching the British troops by surprise. Several soldiers were killed in the storm’s destruction, and the storm stopped the further spread of the fire.

Afterward the admiral asked a Washington lady, “Great God, Madam! Is this the kind of storm to which you are accustomed in this infernal country?”

“No, sir,” the lady replied. “This is a special interposition of Providence to drive our enemies from our city.”

The British left hours later, returning to their ships, which had also suffered damage in the storm.

There is a more detailed account of the storm here.

Interesting note for those of us who love books. The Library of Congress which was then housed in the Capitol, was destroyed by the fire. One year later, Thomas Jefferson sold his personal library to Congress to replace the lost books. More about Jefferson’s library here.

Are you in Isaac’s path? If so, stay safe. Do you have any storm memories? I remember driving in every direction after Hurricane Agnes, looking for a way to get home that wasn’t blocked by water.

I’ll select yesterday’s winner after midnight tonight. So there is still time to comment on guest Laurel Hawkes’ blog for a chance to win.

If you are near Raleigh/Durham, NC, on Wednesday Aug 29, I’m going to be doing a reading from A Not So Respectable Gentleman? at Lady Jane’s Salon. I’d love to see some Risky readers there!