Janet first told us about the Threads of Feeling exhibit on display at the Foundling Museum in London in 2011, and a year later, that it was coming to Colonial Williamsburg. I was so excited I marked my calendar. The chances were great that I’d get to see the exhibit–my in-laws live in Williamsburg.

Janet first told us about the Threads of Feeling exhibit on display at the Foundling Museum in London in 2011, and a year later, that it was coming to Colonial Williamsburg. I was so excited I marked my calendar. The chances were great that I’d get to see the exhibit–my in-laws live in Williamsburg.

This weekend was my chance. We visited the in-laws and I made it a priority to go to the DeWitt Museum where the exhibit will continue until May 27, 2014.

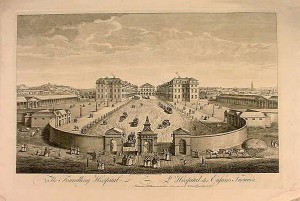

In 1739 philanthropist Thomas Coram received a royal charter from George II to create a foundling hospital for “the maintenance and education of exposed and deserted young children.” It was intended to address the problem of babies being abandoned in the streets or killed because their mothers could not care for them.

At the Foundling Hospital (more like we would consider an orphanage), mothers were asked to provide a token to be kept with the baby’s registration as a way to help match baby to mother, if the mother came to reclaim her child. The tokens left were overwhelmingly swatches of textiles. The exhibit displays book after ledger book, each opened to a page showing a baby’s registration and the token left by the mother.

At the Foundling Hospital (more like we would consider an orphanage), mothers were asked to provide a token to be kept with the baby’s registration as a way to help match baby to mother, if the mother came to reclaim her child. The tokens left were overwhelmingly swatches of textiles. The exhibit displays book after ledger book, each opened to a page showing a baby’s registration and the token left by the mother.

Babies that were left there were only a few days old to two months or so. Initially the hospital only accepted babies under six months of age. Later the age was raised to twelve months. Some of the babies had been named, but all received new names given to them by the hospital. Not all were illegitimate; some married couples gave up their babies because their poverty was so extreme they could not care for them. Some mothers left notes.

It is evident from the tokens that the mothers thought very carefully about what token to leave. Swatches of printed fabrics were cut to show a butterfly or a bird or some other symbol of hope. Some left ribbons of all colors or designs. At that time, ribbons were considered love tokens.

Other tokens were created specifically for the purpose. Hearts were cut out of fabric. Names were cross-stitched. Some swatches were decorated with primitive attempts at embroidery. Others had beautiful crewel work.

One had the overwhelming sense that these babies were loved and that the mothers’ situations were so desperate that giving the baby away to the hospital was the best they could do for them. Their baby would be fed, clothed, educated and apprenticed.

Even though the Foundling Hospital was a popular charity (which continues to this day as Coram), supported by wealthy patrons such as the Duke of Bedford, Hogarth and Handel, it could not afford to care for every baby brought to its doors. From 1749 to 1756, 2,808 babies were brought to the hospital, but only 803 were accepted.

The hospital used a lottery system to decide which baby got in. The mother reached into a bag of balls. If she picked out a white one, her baby could stay. If she picked out a black one, she and her baby were turned away.

This heart breaking policy changed in 1756 when the Foundling Hospital became funded by Parliament and all children up to 12 months old were accepted. The numbers of admissions rose from 200 a year to 4000 a year.

Of those babies accepted, two thirds would die. This horrifying death rate was only a bit higher than the norm of fifty per cent. If a child survived past one year old, chances were great that the child would survive until grown.

The tokens left by the mothers revealed, not only their love for their child, but also the best record available as to what ordinary people wore. Clothing of ordinary people was rarely preserved. Before discovering the tokens, it was assumed that the clothing of the poor was drab. The tokens show that the poor wore colorful clothing, printed fabric, and decorative ribbons.

Most of the fabrics were cotton; most were prints. It was surmised that the demand for cotton, for the masses is what drove the fabric industry to mass produce cloth.

Out of 16,282 children admitted to the Foundling Hospital between 1741 and 1760, only 152 were reclaimed by their mothers.

As I went through the exhibit, reading every page shown, the spirits of the mothers seemed to reach out to me, showing me what an agonizing choice they were forced to make.

As I went through the exhibit, reading every page shown, the spirits of the mothers seemed to reach out to me, showing me what an agonizing choice they were forced to make.

Can you imagine how it must have been? To nurse your baby for two months. To fashion some sort of token as the only communication of your love for the child. To finally make the decision to give up your baby because you loved it so much, then reach into a bag and pick out a black ball.

What did those mothers do then?

Here is a lecture about the Foundling Hospital.

Here is a podcast with John Styles, the man behind the exhibit and the museum book.

Try to visit Williamsburg to see these Threads of Feeling. It is worth it.