Cutting curl papers half an hour … Arranging & putting away my last year’s letters. Looked over & burnt several very old ones from indifferent people … Burnt … Mr Montagu’s farewell verses that no trace of any man’s admiration may remain. It is not meet for me. I love, & only love, the fairer sex & thus beloved by them in turn, my heart revolts from any other love than theirs…

Cutting curl papers half an hour … Arranging & putting away my last year’s letters. Looked over & burnt several very old ones from indifferent people … Burnt … Mr Montagu’s farewell verses that no trace of any man’s admiration may remain. It is not meet for me. I love, & only love, the fairer sex & thus beloved by them in turn, my heart revolts from any other love than theirs…

Could not sleep last night. Dozing, hot & disturbed … a violent longing for a female companion came over me. Never remember feeling it so painfully before … It was absolute pain to me.

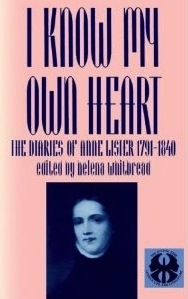

I recently stumbled across an amazing piece of history, the story of Anne Lister of Yorkshire (1791-1840), whose life represents a fascinating alternate history of the Regency. She kept a diary for most of her life which chronicles not only her experiences as a female landowner but also very intimate details of her personal life, coded in a combination of Greek and algebraic symbols.  It’s been described as “the Rosetta stone of lesbian history.”

It’s been described as “the Rosetta stone of lesbian history.”

The BBC made a film of her life in 2010, The Secret Diaries of Miss Anne Lister and there’s a documentary about her which you can find on YouTube, created and narrated by the smart and witty Sue Perkins of the SuperSizers.

Her father was an army captain, a member of a well-established gentry family who lived near Halifax. The only girl in the family, Anne revealed herself as a tomboy, intellectually precocious, smart, able to fence with her brothers and play the flute–“Zorro meets James Galway,” as Sue Perkins describes her. She was sent away to a boarding school in York in 1804 where her overwhelming presence proved so disturbing to the other girls that she was banished to an attic room. There she acquired a roomie, another misfit, the illegitimate daughter of a nabob and an Indian woman, Eliza Raine. They embarked on a passionate love affair, with an exchange of rings and poetry. Now the circumstances weren’t that unusual in an era where men and women were pretty much segregated, and sentimental friendships between young women were common, if not encouraged. But the authorities discovered the phsyical aspects of the relationship, and expelled Anne. Poor Eliza, as the friendship and correspondence faded, fell into a decline and was sent to a lunatic asylum in 1816 where she lived until her death at age 68.

Her father was an army captain, a member of a well-established gentry family who lived near Halifax. The only girl in the family, Anne revealed herself as a tomboy, intellectually precocious, smart, able to fence with her brothers and play the flute–“Zorro meets James Galway,” as Sue Perkins describes her. She was sent away to a boarding school in York in 1804 where her overwhelming presence proved so disturbing to the other girls that she was banished to an attic room. There she acquired a roomie, another misfit, the illegitimate daughter of a nabob and an Indian woman, Eliza Raine. They embarked on a passionate love affair, with an exchange of rings and poetry. Now the circumstances weren’t that unusual in an era where men and women were pretty much segregated, and sentimental friendships between young women were common, if not encouraged. But the authorities discovered the phsyical aspects of the relationship, and expelled Anne. Poor Eliza, as the friendship and correspondence faded, fell into a decline and was sent to a lunatic asylum in 1816 where she lived until her death at age 68.

Anne, back in Halifax, embarked upon a predatory sexual career, probably doing most of her cruising at “the one floozy hotspot where she knew the local lovelies would come in droves” (Sue Perkins)–church. Of course most of the local girls would be extraordinarily flattered to attract the notice of the Queen Bee of the neighborhood, even if they ultimately got more than tea and cakes. Anne’s first affair was with Elizabeth Brown, the daughter of a tradesman. Anne, a real snob, post-conquest noted in her diaries that Elizabeth was dirty and distinctly beneath her socially. (Doesn’t this remind you of Emma taking on–and dropping–Harriet Smith?)

But in 1813 Anne met Marianna Belcombe, who was slightly higher up the social scale, the daughter of a doctor. After some time Marianna married for money (and why not? Anne wasn’t offering to support her). Despite her initial feelings of betrayal, Anne continued their relationship, this time with the frisson of adultery (which technically it wasn’t). But after ten years, Marianna dumped her, telling her that gossip about Anne’s increasingly masculine appearance was becoming embarrassing.

This was not news to Anne.

The people generally remark, as I pass along, how much I am like a man. At the top of Cunnery Lane, three men said as usual, ‘That’s a man’ & one asked ‘Does your c*ck stand?’

But it seems that she also enjoyed her male characteristics, particularly in the thrill of chase and conquest. She liked compliant, pretty women: and, like many of her male counterparts, treated her partners shabbily.

There was a dramatic change in Anne’s life in 1826 when she inherited Shibden House and 400 acres of land. Now she was a force to be reckoned with, one of the elite, and absolutely independent. But she was threatened by the nouveau riche in the area, Halifax being at the heart of industrial expansion. She needed cash. Heck, she needed a wife. And she found one a few miles away, a Miss Ann Walker who was also an heiress.  In 1834 the two women attended Mass at Goodramgate Church in York, followed by a blessing from the clergyman which they felt sanctified their union. They now considered themselves married, and Ann moved into Shibden where they shared their wealth.

In 1834 the two women attended Mass at Goodramgate Church in York, followed by a blessing from the clergyman which they felt sanctified their union. They now considered themselves married, and Ann moved into Shibden where they shared their wealth.

Anne then made a venture into coal mining, one of the best ways for a landowner to get rich, by opening the Walker Mine (aaw). The captains of industry were not amused, in particular one Christopher Rawson, a distant relative of Ann, and a local magistrate. He incited a mob in Halifax to burn the two women in effigy. Was it homophobia or just outrage at an uppity woman (which Anne certainly was)? But Anne got the last laugh. She opened another coal mine, undercut Rawson on prices and forced him to back down.

Anne was a remarkable if not always likeable woman. She was the first woman to be elected to the committee of the Halifax branch of the Literary and Philosophical Society, and a bluestocking who knew Latin, Greek, and geometry. She managed her lands herself and built schools for her tenants. (So in some respects she would have been an excellent romance heroine. Apart from the lesbian thing.)

In addition she traveled widely abroad, visiting not only tourist spots but also factories, prisons, orphanages, farms, and mines.  She also visited the famous Ladies of Llangollen. So it’s sad that on one of her jaunts abroad to Russia in 1839 she died of something quite minor–probably a tick or flea bite–and poor Ann, who outlived her by many decades–brought her body home for burial.

She also visited the famous Ladies of Llangollen. So it’s sad that on one of her jaunts abroad to Russia in 1839 she died of something quite minor–probably a tick or flea bite–and poor Ann, who outlived her by many decades–brought her body home for burial.

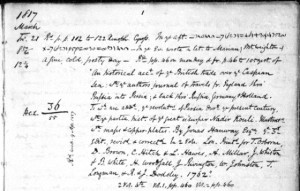

Her diaries–some 26 volumes, over 4 million words, with an index (which surely indicates Anne left them for posterity)–were hidden in Shibden Hall. They were discovered and translated in the 1890s by an indirect descendant, John Lister. But he was advised to hide them once again. During that period, when homosexuality was a crime and the theory that it was hereditary was developed, the revelation of the diaries might have damaged John Lister, who was gay. They were discovered again in the 1930s, when the British censors had their knickers in a twist about Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness–again, not a good time for Anne to posthumously come out.

A local historian ran across them again in the 1960s but the town of Halifax, who now owned the diaries, refused permission to publish. Finally, in 1988, Helena Whitbread decoded them and published them–and sadly, her book is now out of print!

A local historian ran across them again in the 1960s but the town of Halifax, who now owned the diaries, refused permission to publish. Finally, in 1988, Helena Whitbread decoded them and published them–and sadly, her book is now out of print!

I find the life of Anne Lister fascinating. It certainly made me wonder about other relationships of the era–those sentimental friendships, the companions, the friends sharing beds. I also wonder how women without her advantages, of birth and wealth would have fared in a similar relationship. Most middle class women had no choice but to marry–as Amanda Vickery says in Sue Perkins’ documentary, in this period “the ultimate aphrodisiac was the length of a man’s rent roll.”

Had you heard of Anne Lister? Do you have any favorite characters who represent alternate or queer history?

What is the origin of April Fools Day?

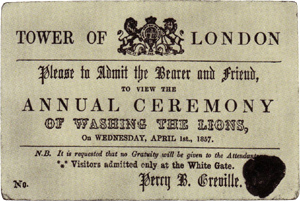

What is the origin of April Fools Day? In 1860 a postcard was sent to several people admitting two to the Tower of London to view the annual ceremony of washing the White Lions on April 1. The invitees were instructed that they would be admitted only at the White Gate.

In 1860 a postcard was sent to several people admitting two to the Tower of London to view the annual ceremony of washing the White Lions on April 1. The invitees were instructed that they would be admitted only at the White Gate.