The winner from our Cara Elliott post is…Penney! Congrats! Please send us your snail mail info at Riskies AT yahoo.com to claim your prize

The winner from our Cara Elliott post is…Penney! Congrats! Please send us your snail mail info at Riskies AT yahoo.com to claim your prize

I’ve been doing lots of reading/research lately for my new projects, a new full-length novel and an “Undone” short story to go with it set in the Elizabethan theater scene! (Alas, they’re both still untitled…) In my reading I noticed that on this day in 1613 the first Globe Theater burned down (this won’t be happening to my fictional theater in the book!). So I thought I would share a bit of my notes for this Tuesday post.

I’ve been doing lots of reading/research lately for my new projects, a new full-length novel and an “Undone” short story to go with it set in the Elizabethan theater scene! (Alas, they’re both still untitled…) In my reading I noticed that on this day in 1613 the first Globe Theater burned down (this won’t be happening to my fictional theater in the book!). So I thought I would share a bit of my notes for this Tuesday post.

Old property records and the discovery of some of the archaeological remains indicate the Globe was sites from the west side of modern Southwark Bridge, east as far as Porter Street and from Park Street south to the back of Gatehouse Square. (Its site was only speculation until part of the foundation, including one original pier base, was found under the Anchor Terrace car park on Park Street in 1989. The materials and some of the shape could be analyzed and preserved, but since most of the foundation lies under another listed building it couldn’t be further excavated).

The Globe was the playing house of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, a troupe owned by actors/shareholders. The main shareholders, brothers Richard and Cuthbert Burbage, owned 25% apiece with four actors owning 12.5% each (Shakespeare, John Heminges, Augustine Phillips , and Thomas Pope. Originally the comedian Will Kempe was intended to be the 7th partner, but he left and sold out his shares to the 4 minority holders. New sharers were added over time). It was built in 1599 using the materials from The Theatre in Shoreditch, built in 1576 by the Burbages’ father James on land which originally had a 21-year lease (but the building he owned outright). But the dastardly landlord, Giles Allen, claimed the building became his on the expiration of the lease, leading to a protracted legal battle. Thus on December 28, 1598, while Allen was out of town for Christmas, the actors dismantled The Theatre and transported it to a warehouse near Bridewell. With the arrival of warmer spring weather, the pieces were ferried over the Thames and reconstructed as The Globe on some marshy garden plots south of Maiden Lane in Southwark!

The Globe was the playing house of the Lord Chamberlain’s Men, a troupe owned by actors/shareholders. The main shareholders, brothers Richard and Cuthbert Burbage, owned 25% apiece with four actors owning 12.5% each (Shakespeare, John Heminges, Augustine Phillips , and Thomas Pope. Originally the comedian Will Kempe was intended to be the 7th partner, but he left and sold out his shares to the 4 minority holders. New sharers were added over time). It was built in 1599 using the materials from The Theatre in Shoreditch, built in 1576 by the Burbages’ father James on land which originally had a 21-year lease (but the building he owned outright). But the dastardly landlord, Giles Allen, claimed the building became his on the expiration of the lease, leading to a protracted legal battle. Thus on December 28, 1598, while Allen was out of town for Christmas, the actors dismantled The Theatre and transported it to a warehouse near Bridewell. With the arrival of warmer spring weather, the pieces were ferried over the Thames and reconstructed as The Globe on some marshy garden plots south of Maiden Lane in Southwark!

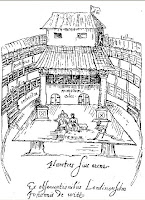

The Globe’s actual dimensions are unknown, but evidence suggests it was a 3-story, open-air space about 100 feet in diameter that could fit in about 3000 spectators. In a famous sketch of the period done by Wenceslas Hollar it’s shown as round, but the excavations show it was actually a polygon of 20 sides. At the base of the stage is the pit, or yard, where for a penny the groundlings would stand on the dirt, rush-covered floor to watch the play (and eat and drink and fight). Around the yard rose 3 levels of stadium-style seating, each level more expensive (audience members would pay at the door of their chosen level). There were also private boxes for very wealthy people.

The Globe’s actual dimensions are unknown, but evidence suggests it was a 3-story, open-air space about 100 feet in diameter that could fit in about 3000 spectators. In a famous sketch of the period done by Wenceslas Hollar it’s shown as round, but the excavations show it was actually a polygon of 20 sides. At the base of the stage is the pit, or yard, where for a penny the groundlings would stand on the dirt, rush-covered floor to watch the play (and eat and drink and fight). Around the yard rose 3 levels of stadium-style seating, each level more expensive (audience members would pay at the door of their chosen level). There were also private boxes for very wealthy people.

The stage, an apron-style thrust stage, went out into the middle of the yard and was about 43 feet wide, 27 feet deep, and raised about 5 feet from the ground. In the middle was a trap door for ghosts and such to enter the scene. Large, faux-marble painted columns on either side supported the roof over the rear of the stage (the ceiling of this was called the “heavens” and was painted to resemble the sky. There was another trap door here where actors could be lowered using a harness–literally a deus ex machina!). The back wall had two or maybe three doors at the main level, with a curtained inner stage in the center and a balcony above. These doors went into the tiring house, a sort of green room where costumes could be changed and actors waited for the cues. Musicians used the balcony and it could also be used as scenery (like the balcony scene of Romeo and Juliet).

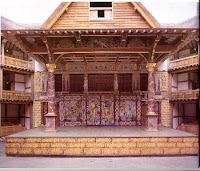

This Globe had a glorious run, seeing the premiere of most of Shakespeare’s great plays as well as hundreds of works now lost (or at least more obscure!). But on June 29, 1613 the thatched roof was set on fire by a cannon fired in a performance of the play Henry VIII and the Globe burned to the ground (though no lives were lost!). By then Shakspeare was mostly in retirement in his fine new house in Stratford, and would die 3 years later. The Globe was built again in 1614, with a tile roof replacing the thatch. In 1642 the new Puritan government closed down all the country’s theaters and the Globe was pulled down to make way for tenements. It came back to life in 1997, about 750 feet from the original on the banks of Thames.

This Globe had a glorious run, seeing the premiere of most of Shakespeare’s great plays as well as hundreds of works now lost (or at least more obscure!). But on June 29, 1613 the thatched roof was set on fire by a cannon fired in a performance of the play Henry VIII and the Globe burned to the ground (though no lives were lost!). By then Shakspeare was mostly in retirement in his fine new house in Stratford, and would die 3 years later. The Globe was built again in 1614, with a tile roof replacing the thatch. In 1642 the new Puritan government closed down all the country’s theaters and the Globe was pulled down to make way for tenements. It came back to life in 1997, about 750 feet from the original on the banks of Thames.

In my book, the heroine’s father is an entrepreneur theater owner (much like James Burbage or Philip Henslowe) and the hero is an actor/playwright/troublemaker/spy, so I’ve been having a wonderful time reading about the bawdy, wild, genius world of the Elizabethan theater! Originally I had the idea on my trip to London a couple years ago, when I got to attend A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the new Globe. I knew I would have fun there, but I didn’t expect how magical it all would feel! If I ignored the modern dress of the audience, and the fact that really they were all very polite (no throwing of anything on stage or stuff like that!) I could almost imagine being transported back to the 1590s. It’s a very different feeling from modern theater-going, it seemed more intimate, as if the audience was part of the action onstage. And the actor playing Lysander was very dishy. :))

In my book, the heroine’s father is an entrepreneur theater owner (much like James Burbage or Philip Henslowe) and the hero is an actor/playwright/troublemaker/spy, so I’ve been having a wonderful time reading about the bawdy, wild, genius world of the Elizabethan theater! Originally I had the idea on my trip to London a couple years ago, when I got to attend A Midsummer Night’s Dream at the new Globe. I knew I would have fun there, but I didn’t expect how magical it all would feel! If I ignored the modern dress of the audience, and the fact that really they were all very polite (no throwing of anything on stage or stuff like that!) I could almost imagine being transported back to the 1590s. It’s a very different feeling from modern theater-going, it seemed more intimate, as if the audience was part of the action onstage. And the actor playing Lysander was very dishy. :))

Here are a few books I’ve been using as I get into the story:

JR Mulryne and Margaret Shewring, Shakespeare’s Globe Rebuilt (1997: lots of great, in-depth info about the evidence of the original Globe and how it was used and adapted for modern requirements in the new Globe)

Julian Bowsher and Pat Miller, The Rose and the Globe–Playhouses of Shakespeare’s Bankside, Southwark (2010–a brand new publication from the Museum of London which someone kindly sent me, it’s great)

James Shapiro, 1599: A Year in the Life of William Shakespeare (2005)

Thomas Dekker, The Gull’s Hornbook (1609, reprinted in 1907–a fabulous source for the very colorful life of the Elizabethan underworld!)

Andrew Gurr, The Shakespearean Stage 1574–1642 (1991) and Playgoing in Shakespeare’s London (1987)

RA Foakes and RT Rickert, eds, Philip Henslowe’s Diary (1961–a must-read for anyone interested in the theater of this period)

Richard Dutton, Mastering the Revels: The Regulation and Censorship of English Renaissance Drama (1991)

The Cambridge Companion to English Renaissance Drama (1990)

Park Honan, Christopher Marlowe, Poet and Spy (2005)

The Globe website

Shakespeare Resource Center

The Old Globe Theater History

What’s your favorite theater-going memory? Any favorite plays (Shakespeare or otherwise!)??

The Riskies are happy to welcome back Cara Elliott, who kindly agreed to blog about the background of book 2 her “Circle of Sin” series–To Surrender to a Rogue! Comment for a chance to win a copy…

The Riskies are happy to welcome back Cara Elliott, who kindly agreed to blog about the background of book 2 her “Circle of Sin” series–To Surrender to a Rogue! Comment for a chance to win a copy…

Hi everyone,

It’s a pleasure to be back visiting the Riskies! Yes, yes, I know–I was just here in March, but after a long interlude between series, the first two books of my new trilogy have been released close together. So I’m back to talk about To Surrender to a Rogue, which takes place in Bath amidst an archaeological excavation of Roman ruins.

It’s a pleasure to be back visiting the Riskies! Yes, yes, I know–I was just here in March, but after a long interlude between series, the first two books of my new trilogy have been released close together. So I’m back to talk about To Surrender to a Rogue, which takes place in Bath amidst an archaeological excavation of Roman ruins.

The “Circle of Sin” features 3 beautiful, brainy female scholars who each has a dark secret in her past. The first book, To Sin With a Scoundrel, highlighted Ciara, the chemistry expert. The current release tells Alessandra’s story. She’s an expert on ancient antiquities, a subject that has fascinated me since I saw a PBS documentary on the Pyramids when I was very little. (I disntinctly remember many days of climbing the hill behind my elementary school during recess, pretending that I was an intrepid explorer scaling the rough-cut rocks to the pinnacle!)

I also have a soft spot in my heart for the hero’s passion. Jack is a highly talented watercolorist, and as art is my background, I’m going to eschew talking about the techniques of digging in favor of painting a brief picture on the subject of pigment and papaer. So without further ado…

Most Regency stories depict watercolor painting as a proper pursuit for young ladies–which it was. However, it was also a subject of serious study for young men. One of the leading watercolorists of the 1700s, Alexander Cozens, taught at Eton for years. In addition to producing hauntingly beautiful works of his own, rendered in an austere, monochromatic palette, he shaped the artistic tastes of a whole generation of English aristocrats. Two of his pupils, Sir George Beaumont and William Beckford, are reocgnized as two of the greatest collectors and connoisseurs of their age.

Most Regency stories depict watercolor painting as a proper pursuit for young ladies–which it was. However, it was also a subject of serious study for young men. One of the leading watercolorists of the 1700s, Alexander Cozens, taught at Eton for years. In addition to producing hauntingly beautiful works of his own, rendered in an austere, monochromatic palette, he shaped the artistic tastes of a whole generation of English aristocrats. Two of his pupils, Sir George Beaumont and William Beckford, are reocgnized as two of the greatest collectors and connoisseurs of their age.

The Royal Academy, which was founded in 1768, recognized the medium, but for the most part its practitioners were treated as second class citizens by the artists who worked in oil paints. Tired of being dismissed as mere craftsmen rather than creative talents, a group of artists banded together and made a bold move, establishing the Society for Painters in Water-Colours in 1804. (In previous centuries, watercolorists traditionally worked with mapmakers and were seen as recorders of topographical scenes). They held their own shows, which proved to be a critical and financial success. From JMW Turner and Thomas Girtin’s evocative use of color and texture in landscapes to David Roberts’s striking depictions of exotic travel destinations, Regency watercolorists were embraced by the public as true artists. (Roberts in particular served as a model for my hero–his paintings of classical sites in the East were wildly popular with a British audience whose travel opportunities were severely limited by the Napoleonic Wars).

The Royal Academy, which was founded in 1768, recognized the medium, but for the most part its practitioners were treated as second class citizens by the artists who worked in oil paints. Tired of being dismissed as mere craftsmen rather than creative talents, a group of artists banded together and made a bold move, establishing the Society for Painters in Water-Colours in 1804. (In previous centuries, watercolorists traditionally worked with mapmakers and were seen as recorders of topographical scenes). They held their own shows, which proved to be a critical and financial success. From JMW Turner and Thomas Girtin’s evocative use of color and texture in landscapes to David Roberts’s striking depictions of exotic travel destinations, Regency watercolorists were embraced by the public as true artists. (Roberts in particular served as a model for my hero–his paintings of classical sites in the East were wildly popular with a British audience whose travel opportunities were severely limited by the Napoleonic Wars).

Okay, so many of you have probably dabbled in “watercolors.” But the stuff of grade school art class is a far cry from the “real” thing. So here is primer on the materials and techniques that Regency artists used to create their richly nuanced paintings:

As opposed to oil paints, watercolors are transparent, and an artist builds color, texture, depth and shadow by layering washes of pigment. (There are opaque watercolors, which are made of pigments mixed with white zinc oxide–these are called “body color” by the English, but are more commonly known by the French name of gouache. However, that’s another subject!). Transparent watercolor “paint” is made up of finely ground mineral or organic particles, bound together with two maind additives: gum arabic, which helps adhere the pigment to the paper, and oxgall, a wetting agent which helps disperse the pigment in an even wash. In Regency times, the pigments were formed into a solid square or cake, which would be carried in a wooden paint case. (Tubes of viscous paints were invented by Windsor and Newton in 1846).

An artists would dip his brush in water, then dab it over the block of pigment to dissolve it. The amount of water used determines the intensity of the color. Most artists start with very light washes to lay in the basic elements of their composition, then build depth and details. There are a vast array of pigments, and their names are wonderfully evocative on their own–alizarin crimson, yellow ochre, Vandyke brown, cerulean blue, to name but a few.

If you look closely at a watercolor painting, you may see a faint tracing of lines beneath the color. Many artists used graphite pencils to make a preliminary sketch of the subject. Charcoal (the solid carbon residue from charred twigs heated in an airtight chamber) or black chalk (carbon mixed with clay and gum binders) were also used. They produced a softer, but usually darker line. For some artists, these line sketches were deliberately strong and were used as an intergral part of the finished painting.

If you look closely at a watercolor painting, you may see a faint tracing of lines beneath the color. Many artists used graphite pencils to make a preliminary sketch of the subject. Charcoal (the solid carbon residue from charred twigs heated in an airtight chamber) or black chalk (carbon mixed with clay and gum binders) were also used. They produced a softer, but usually darker line. For some artists, these line sketches were deliberately strong and were used as an intergral part of the finished painting.

Paper is an important component of a watercolor painting because its texture affects the look of the washes. James Whatman created “wove” paper in the 1750s, which quickly became popular with the artists. Wove paper uses a fine wire mesh screen as a mold, making a finer surface than the earlier “laid” papers. This allowed a more uniform wash. (Whitman is still a highly regarded brand today!). The paper made by Thomas Creswick, which offered a rich assortment of textures, was also popular. Another favorite was “scotch” paper, made from bleached linen sailcloth. It had a more rustic feel, and featured imperfections such as specks of organic matter that some artists felt added more interest to their paintings.

Brushes are made from a variety of furs. During the Regency, squirrel was favored for soft, wide brushes designed to lay in broad washes. But the very best ones were made of asiatic marten–or Russian sable–as they held their shape very well and could be twirled to a very fine point in order to paint in detail.

Brushes are made from a variety of furs. During the Regency, squirrel was favored for soft, wide brushes designed to lay in broad washes. But the very best ones were made of asiatic marten–or Russian sable–as they held their shape very well and could be twirled to a very fine point in order to paint in detail.

So, now that you’re all art experts, which do you prefer–watercolor or oil painting? And do you have a favorite artist? I’m a big fan of Turner and Constable (both of whom painted wonderful images in both mediums).

To celebrate the release of To Surrender to a Rogue, I’ll be giving away a signed copy of the book to a lucky winner!

Our three winners on the Harlequin Historicals Silk & Scandal posts are–Kirsten, Barbara E, and Louisa Cornell! Please send us your snail mail info at Riskies AT yahoo.com, and thanks for visiting!

Last weekend, I spent some time digging through my Big Research Box, looking for info for the RomCon workshop I’ll be taking part in at Denver in a couple weeks (“Stripping the Heroine,” all about what the historical heroine would be wearing!). My Big Research Box is, well, just what it sounds like–a big plastic storage tub with folders holding notes and articles and inspirational images. I try to be organized and divide them up by era and subject, i.e. “Regency–Architecture” or “Elizabethan–Music,” but often I get lazy and stuff things in wherever there’s room. So there was info on Regency fashion in several folders, and hours had gone by before I knew it!

It made me think about the importance of fashion and style to character and story. Even when I don’t describe what characters are wearing in a scene or what they have in their armoire, I can see them in my mind. What people choose to wear says so much about them–whether they know it or not. (One of my favorite style blogs, formerly-known-as-Project Rungay, have been doing an in-depth study of the costumes on Mad Men and how they delineate a character’s progress and state of mind. Great stuff!)

I also thought of this recently when I saw a great exhibit at the Oklahoma City Museum of Art, “From Sketch to Screen,” featuring a lovely selection of film costumes, from an elaborate court dress worn by Greta Garbo in Queen Christina and a white Givenchy suit worn by Audrey Hepburn in Funny Face, to superhero outfits from X-Men and Superman, it covers a wide spectrum. This concept of costume=characters is, of course, totally vital in a visual medium like film. Here are just a few of the costumes that were there (photos weren’t allowed so these are just movie stills; there are a few pics of the exhibit itself at the museum’s site):

This purple gown from Elizabeth: The Golden Age

This purple gown from Elizabeth: The Golden Age

This little beaded leotard from Moulin Rouge (plus the hat and shoes!)

This little beaded leotard from Moulin Rouge (plus the hat and shoes!)

This dinner gown from Titanic (even more gorgeous in person! They also had the blue velvet suit)

This dinner gown from Titanic (even more gorgeous in person! They also had the blue velvet suit)

Three costumes from Gone With the Wind, including this one (though they are reproductions; the originals didn’t survive)

The famous green dress from Atonement, one of my favorites! (It wasn’t displayed very well, though, at least not for people who want to see details of design! The straps are too fragile for a mannequin so it was just sort of pooled in a little glass case with only the bodice able to be seen clearly. I wish it had been laid out full-length)

The famous green dress from Atonement, one of my favorites! (It wasn’t displayed very well, though, at least not for people who want to see details of design! The straps are too fragile for a mannequin so it was just sort of pooled in a little glass case with only the bodice able to be seen clearly. I wish it had been laid out full-length)

Some sparkly jumpsuits from Mamma Mia!

One of Renee Zellwegger’s sequined dresses from Chicago

One of Renee Zellwegger’s sequined dresses from Chicago

Two of the little sailor suits from The Sound of Music (so wee and cute!)

Two of the little sailor suits from The Sound of Music (so wee and cute!)

The white furred cloak Vanessa Redgrave wore on her way to Camelot

The white furred cloak Vanessa Redgrave wore on her way to Camelot

You can see how clearly these costumes represent the characters wearing them (and not just how annoyingly skinny Nicole Kidman and Cate Blanchett are!). Elizabeth I, Rose from Titanic, Guinevere, Scarlett, Cecelia from Atonement, are all right there in these garments, wrapped up in lace, beads, and silk. I found it to be a very helpful lesson in my own search for my characters. (And even though I would have loved to see a Regency movie included in the selection, I also liked the variety!)

What are your favorite movie costumes, or memorable clothes read about in a book? (I always think of Villiars in Judith Ivory’s Untie My Heart and the scene in the bank–that has to be the sexiest coat ever!). What do you think clothes say about characters?

(And if you’re in Oklahoma City before August, I highly recommend a look at this exhibit!)