Hurrah! I finally got my hands on John Philip Kemble’s version of Shakespeare’s THE WINTER’S TALE.

Hurrah! I finally got my hands on John Philip Kemble’s version of Shakespeare’s THE WINTER’S TALE.

For those of you who don’t know — during the Regency (and for a while before), Kemble was an actor and manager at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane, and later Theatre Royal Covent Garden. He valued Shakespeare highly. Under his wise yet despotic rule, London theatre saw (for the first time in a long time) Shakespeare plays that the bard himself might actually have recognized.

By contrast, the Great Garrick (the theatre despot in the early to mid 18th century), although respected for also being a restorer of Shakespeare to high repute, nonetheless produced things like “Florizel and Perdita” and “Catherine and Petruchio” — hour-long things that were part Shakespeare, part bizarre rewriting. Even better: in Garrick’s King Lear, Lear and Cordelia live, and Cordelia marries Edgar.

Kemble, though, did his best to be true to Shakespeare.

The illustration here, by the way, is Sarah Siddons playing Hermione in THE WINTER’S TALE.

The illustration here, by the way, is Sarah Siddons playing Hermione in THE WINTER’S TALE.

My favorite part of reading Kemble’s versions of Shakespeare is seeing just how prudish (or not prudish) the Regency stage was. My conclusions in the past have been that, though Regency theatregoers clearly tolerated less vulgarity than their Elizabethan ancestors, Kemble’s scripts are far closer to Shakespeare’s than to Bowdler’s.

Or, to be more precise, sex and violence are welcomed on Kemble’s stage, but indelicate expressions rather less so. (For example, the characters still talk about virginity, but don’t use such a crude word for it, instead terming it purity or honour or the like.)

(To read my earlier posts on the subject, click Regency Shakespeare or Regency AS YOU LIKE IT.)

So much for my past impressions of Kemble’s changes. Now, today’s project: let’s find some bits in THE WINTER’S TALE which Kemble changed!

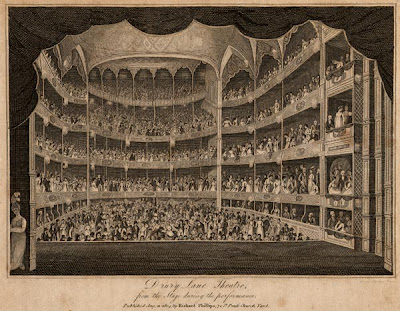

This is a picture of Drury Lane Theatre in 1804.

This is a picture of Drury Lane Theatre in 1804.

What follows is the original passage of Shakespeare’s in which King Leontes rants (half-madly) about his conviction that his wife has slept with his best friend, and is pregnant with the friend’s child. I have put in purple the portions that Kemble cut out:

There have been,

Or I am much deceiv’d, cuckolds ere now;

And many a man there is (even at this present,

Now, while I speak this) holds his wife by th’ arm,

That little thinks she has been sluiced in ‘s absence

And his pond fish’d by his next neighbour, by

Sir Smile, his neighbour; nay, there’s comfort in’t,

Whiles other men have gates, and those gates open’d,

As mine, against their will. Should all despair

That have revolted wives, the tenth of mankind

Would hang themselves. Physic for’t there’s none;

It is a bawdy planet, that will strike

Where ’tis predominant; and ’tis powerful, think it,

From east, west, north, and south; be it concluded,

No barricado for a belly. Know ‘t,

It will let in and out the enemy,

With bag and baggage: many thousand on ‘s

Have the disease, and feel ‘t not.

When the first cut above appears, Kemble has Leontes trail off (indicated by a long dash), and a hand-written stage direction reveals that another character approaches Leontes at this point (the implication perhaps being that Leontes would have finished the thought, had he not feared being overheard.)

So, that’s one example of things Kemble cut out. What are some passages, risque though they might be, that Kemble let alone? Here are a few:

You may ride us,

With one soft kiss, a thousand furlongs, ere

With spur we heat an acre.

How she holds up the neb, the bill to him!

And arms her with the boldness of a wife

To her allowing husband!

Go, play, boy, play;–thy mother plays, and I

Play too; but so disgrac’d a part, whose issue

Will hiss me to my grave;

My wife ‘s a hobby-horse; deserves a name

As rank as any flax-wench, that puts to

Before her troth-plight:

There you have it! Kemble’s alterations of Shakespeare — one of my little obsessions.

However, I have no idea if any of you are at all interested in this subject. I could happily do more posts detailing which bits of Shakespeare Kemble left in, and which he cut out — but I’ll only do so if I know it’s of interest to someone! So if you’re interested, do let me know in a comment.

And remember: our next Jane Austen bookclub meets the first Tuesday in September, to discuss the Ang Lee/Emma Thompson version of SENSE AND SENSIBILITY!

Cara

who thinks those flax-wenches got a bad rap

Didn’t Garrick also have Romeo and Juliet live as well? I’ve always loved comparing Dryden’s play All for Love (Restoration) with Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra and Nahum Tate’s Lear with Shakespeare as well. I would love to hear more about Kemble and his Shakespeare, particularly since his sister the great Mrs. Siddons was known for her Shakespearean interpretations.

This is something of which I know NOTHING about, Cara! So it is interesting to me!

Since I recently played the part of Leontes in A Winter’s Tale, I take a particularly keen interest in what parts of his speeches were considered too shocking for Regency audiences. It’s a pity those lines were lost…they’re ones where Leontes can go completely over the top, stark raving bonkers crazy mad. But in a good way. 🙂

I find very interesting the distinction between excising references to sex per se, and excising references that the audience might find vulgar. Nowadays I think we are tolerant of some kinds of vulgarity, in certain contexts; and we are also tolerant of some sexual references, in certain contexts; but the two contexts are not necessarily the same.

It makes me think about some of the extremes of Victorianism. For example, referring to a piano’s “limbs” was probably more because the word “legs” had become vulgar (by association) than out of fear that musical instruments would lead to lustful thoughts.

Todd-who-will-strike-where-tis-predominant

Didn’t Garrick also have Romeo and Juliet live as well?

Elizabeth Kerri (or do you just go by Elizabeth?), I suspected so, but a quick look shows them properly dead at the end. Then again, that’s in his published version — no telling whether it’s the only version he did!

Cara

I always thought Romeo and Juliet should have lived to have a happily ever after…

I think it’s always interesting to see what changes people make to plays or books. . . alas, we can’t see Kemble’s DVD director’s cut extra disk, but hey, it’s close. LOL 🙂 It’s funny how he thought some things were too vulgar or the like, because I would figure if it’s Shakespeare, everyone knew it, everyone learned it so you’d expect to hear those lines. But alas, there is always that interpretation that directors want to do. . . wonder if those audiences did what we do when a book becomes a movie, discuss what was good and what was horrible. LOL 🙂

Lois

Here’s an exhibit at the Folger in Washington DC I thought Cara and others might be interested in>

September 20, 2007–January 5, 2008

Marketing Shakespeare:

The Boydell Gallery (1789–1805) and Beyond

Explore the birth of the Shakespeare market in Jane Austen’s England with paintings and engravings from the fashionable Boydell Gallery in London. Then view a variety of Shakespeare knick-knacks inspired by famous actors of the time such as Sarah Siddons and John Philip Kemble: figurines, jewelry, enamel boxes, and Wedgewood objects.

http://www.folger.edu

I meant to reply sooner, but I’ve been without internet for a couple days now. (And without phone. And without cable TV. Word of advice: never get all three from the same cable provider. Especially if said cable provider is EVIL.)

Lois, I love your idea of Kemble having a director’s commentary to enlighten us! (And let’s give Shakespeare a writer’s commentary too, while we’re at it.)

It’s funny how he thought some things were too vulgar or the like, because I would figure if it’s Shakespeare, everyone knew it, everyone learned it so you’d expect to hear those lines.

Well, they did publish expurgated versions, too, so perhaps everyone didn’t know all the lines!

Plus, to a certain extent, I think it’s just a different sensitivity. Nowadays, most audiences wouldn’t mind a director cutting out certain racist epithets — audiences find them very unpleasant to hear, even while understanding (usually) that they were common expressions in the time the thing was written.

So perhaps Regency-era audiences knew perfectly well the more vulgar things Shakespeare said, but really didn’t want to hear them uttered aloud (particularly in mixed company.)

Cara

wonder if those audiences did what we do when a book becomes a movie, discuss what was good and what was horrible. LOL 🙂

Ooh, I love it, Lois! That would make a very funny scene in a Regency:

“Why in the world would he cut out “virginity” while leaving “virgin” in?” asked Lord Everso. “What’s wrong with “virginity””

“Nothing I can’t cure,” smirked Lord Rakehell.

Cara

And Janet, thanks for the info on the exhibit! Very much up my alley. (And boulevard, and avenue…)

Cara