How I’d love to see that sentence in a regency. Since music was such a major part of Jane Austen’s life–and that of her heroines–I thought I’d blog about that today, as we recover from the rigors and excitement of our contest (congratulations, winners!). Some soothing piano music might help, too.

How I’d love to see that sentence in a regency. Since music was such a major part of Jane Austen’s life–and that of her heroines–I thought I’d blog about that today, as we recover from the rigors and excitement of our contest (congratulations, winners!). Some soothing piano music might help, too.

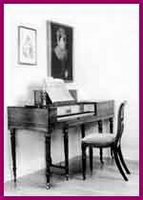

Jane Austen’s music books–copied by hand–are at her house in Chawton, Hants, as is her piano (left), made in 1810 by the composer Clementi, who owned one of the major piano manufacturers in London. One of Clementi’s rivals was the firm of John Broadwood & Sons, still in business, and serving as providers of pianos to royalty ever since George II’s time. The gorgeous instrument above was made by Zumpt & Buntebant of London and taken by Johann Christian Bach (son of the great J.S.) when he and the young Mozart visited France in 1778.

Jane Austen’s music books–copied by hand–are at her house in Chawton, Hants, as is her piano (left), made in 1810 by the composer Clementi, who owned one of the major piano manufacturers in London. One of Clementi’s rivals was the firm of John Broadwood & Sons, still in business, and serving as providers of pianos to royalty ever since George II’s time. The gorgeous instrument above was made by Zumpt & Buntebant of London and taken by Johann Christian Bach (son of the great J.S.) when he and the young Mozart visited France in 1778.

Jane’s favorites included Clementi, Haydn and lesser-known composers Pleyel, Eichner and Piccini. Here’s a recollection from her niece Caroline:

Aunt Jane began her day with music – for which I conclude she had a natural taste; as she thus kept it up – ‘tho she had no one to teach; was never induced (as I have heard) to play in company; and none of her family cared much for it. I suppose that she might not trouble them, she chose her practising time before breakfast – when she could have the room to herself – She practised regularly every morning – She played very pretty tunes, I thought – and I liked to stand by her and listen to them; but the music (for I knew the books well in after years) would now be thought disgracefully easy – Much that she played from was manuscript, copied out by herself – and so neatly and correctly, that it was as easy to read as print.

Jane’s piano is a square fortepiano–the term used for early pianos. The great technological breakthrough of the piano (or whatever you want to call it!) is that unlike its predecessor the harpsichord it offered dynamic control–hence it’s name, Italian for loud-soft, and used a hammer action, not a plucking action, on the strings. Fortepianos were first produced in the mid-eighteenth century and were built entirely of wood (modern pianos are held together with a large steel band to hold in the formidable tension of the strings), and have a more delicate, subtle sound than modern pianos. To hear the instrument go to this recording of Mozart and Schubert on amazon, where you can listen to excerpts. The artist is Melvyn Tan, who performed the fortepiano music heard on the movie Persuasion.

Here are a couple more recordings available from the Jane Austen Museum in Bath. A Very Innocent Diversion features selections from Jane Austen’s music collection while the other features music from Jane Austen’s time performed in Bath.

Would music–daily piano practice– feature in your Regency fantasy or nightmare? Or, like Mrs. Elton, would you gratefully become a talker (although not totally devoid of taste, of course) and not a practitioner once you succumbed to the rigors of married life? And as (Cara, I think?) said, it might be interesting to see how truly accomplished those young ladies were…hopefully none of us would be like Mary Bennett, plucked from the keyboard by her embarrassed papa. And do you think that if you were magically transported back to Regency times, you might miss being able to summon music at the push of a button, or do you think the comparative rarity of a live performance (a good one, that is) might heighten your appreciation?

Janet