So I spent most of the day staring at my computer screen half-petrified because I realized this morning that today is April Fool’s day & I have to write a post &, oh my gosh, do I need to write something funny?!!?!? I’ve toyed with several amusing headlines – “The Riskies Will Only Write Zombie Books From This Day On! (and our heroes’ manly appendages will all fall off all the time!!) (or something),” or, “We Just Wanted To Tell You That We Are All Aliens From Outer Space Pretending To Be Romance Authors, But Please Don’t Mind Us & Carry On” – but, well…

Instead of talking about zombies, wonky manly appendages, and aliens, I’ve decided to turn to much nicer things, like my super-seekrit project: I’ve taken part in a multi-author box set of sweet romances, which came out earlier this week. And did I mention that the box set is free? 🙂

I also caved in and added a few more titles to my research library. Among other things, I’ve finally ordered Chatsworth: The Attic Sale, the catalogue of the auction at Sotheby’s in 2010. In expect to find many interesting items in there! Here’s a short YouTube video about the auction:

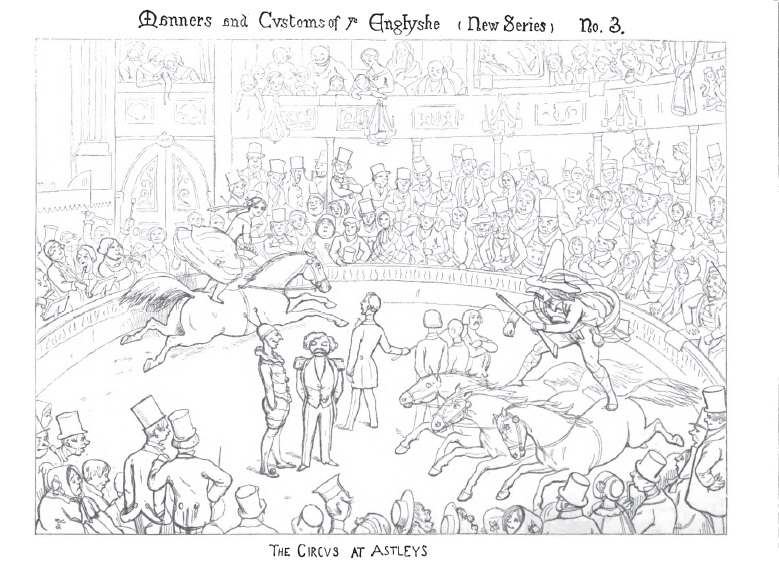

Moreover, I also stumbled across a number of fascinating research experiments in the form of historical enactments, of which two are of particular interest to the Regency period: in Pride & Prejudice: Having a Ball a Regency ball is staged at Chawton House, the estate of Austen’s brother. The documentary is only 90 minutes long (or rather, short), but it still provides some fascinating insights into the practicalities of preparing the food, of the dancing itself, and the supper that followed.

And then I also found a series about music in the country house. I briefly dipped my toe into this field when I wrote Springtime Pleasures and had my heroine swapping music books with her new friend. “Music’s Hidden Histories” is a joint project of the University of Southampton and Tatton Park. The short videos are all available via the Humanities Southampton YouTube channel:

For now, though, I’m going to return to Roman antiquity and my dashing centurion Marcus Florius Corvus. I’m really looking forward to celebrate the launch of this new series with you next month!

You can find Love Is All You Need on Amazon US, UK, CA, Kobo, Apple, B&N. Happy reading!