If you follow this blog at all, you know I fall down all kinds of rabbit holes and this was a very interesting one. Technically, I was researching how letters were addressed before there were postal codes or even house numbers, but when I went to the website of the British Postal Museum, first there was a sidebar about postmen’s uniforms (exhibit “Dressed to Deliver” runs to Sept 24). I love anything about historical clothing, so could not resist that! Included was an example of one worn by a Thames River Postman. A what? I could not pass up investigating, and stumbled into what I think is a really fascinating Regency-related story!

The River Thames in London was a huge center of shipping activity during the Regency. The Pool of London was the area below London Bridge where thousands of huge ships moored and thousands more small vessels tended to them, while intermixed with them were houseboats and many other smaller crafts. Regina Walker has a great blogpost about that: https://reganromancereview.blogspot.com/2017/02/the-port-of-london-in-18th-century.html

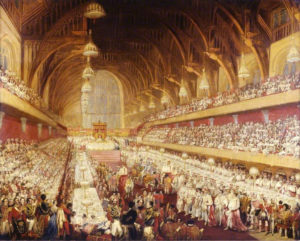

The Pool of London by John Wilson Carmichael

The Pool of London by John Wilson Carmichael

In 1800, an enterprising Thames Waterman (guild member of the Waterman and Lightman Company) named William Simpson petitioned the Post Office to create the position of River Postman to service the ships. Another man had proposed such a service in the 1790’s but had been turned down. The need was significant and Simpson obtained signatures from merchants, captains, and ship owners to support his request. The duties were to “deliver and collect letters from the various vessels on the river, deliver goods and occasionally ferry people.”

The work was hazardous. As explained on the Postal Museum blog, “All year round they had to manage the tide, winds, cold and fog – not to mention the ships and barges….” All of which meant the job required a high level of skill. Simpson’s assistant drowned while on the job in 1803. Simpson himself died in 1806 from injuries he sustained on a ship while making a delivery.

A later River Postman wrote in 1821: “I must inform you of the accident that happened to the Post Boat on Monday through the violence of the wind. I was delivering a letter on board the Ship Albion near the Tower, when a barge came down and sunk the boat and with great difficulty, I saved my life.”

“Pool of London” by Thomas Luny (1801-1810)

“Pool of London” by Thomas Luny (1801-1810)

When Simpson died, his widow petitioned the Post Office to put their sixteen-year-old son in his father’s position. He was too young, but as he had already been helping his father with the job, the Post Office decided to allow it.

William (Junior) worked at it for four years without incident. But when the young man was 20 years old for some reason he succumbed to the temptation that access to all this mail provided and stole some mail and a £20 note and fled, taking “a Hackney Coach about 10 o’Clock last night from Brick Fields, Dock Head.” Scandal!!

“Pool of London, Below London Bridge” by Samuel Atkins (1790) at the Courtauld Gallery, London

“Pool of London, Below London Bridge” by Samuel Atkins (1790) at the Courtauld Gallery, London

A reward of £100 was issued, payable on conviction, to anyone who apprehended him. William Junior was caught eventually at the Swan public house, Forest Row, East Grinstead, East Sussex, and sat in London’s Newgate Prison until the time of his trial. In October of 1810 he was convicted and sentenced to hang, although due to his age his sentence was reduced to transportation to Australia to labor there for life.

The scandal did not end of the Thames River Postal Delivery Service, however. Young William’s assistant, Samuel Evans, took over the position and served faithfully until 1832 (making him the one whose report I quoted above). When he retired, his son took it on. That was the start of a family dynasty that lasted until the River Postal Service ended in 1952, served by six successive members of the Evans family.

Did you know about this specialized postal service that began during the extended Regency?