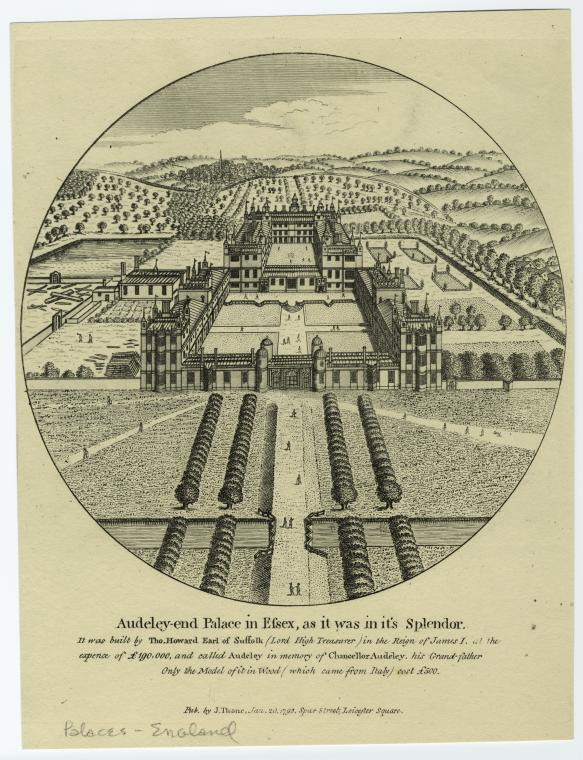

“The rooms are high and hung with beautiful tapestries […] [and] the staircases are built with peculiar comfort: after every five steps there is a landing so that one can rest and does not get out of breath.”

Johann Ernst von Sachsen-Weimar about Audley End

This past weekend, I went on a short trip to London to meet up with online friends. And what does a historically-minded person do when in Britain? Visit a stately home of course! This time around the stately home in question was Audley End in Essex, which in many ways is an excellent example of the varied history of British country houses.

This past weekend, I went on a short trip to London to meet up with online friends. And what does a historically-minded person do when in Britain? Visit a stately home of course! This time around the stately home in question was Audley End in Essex, which in many ways is an excellent example of the varied history of British country houses.

The current house is built on the foundations of a 12th-century Benedictine monastery, Walden Abbey, which fell to the Crown during Henry VIII’s dissolution of monasteries in the wake of his break from the Church of Rome. Henry gifted the house and its environs to one of his most trusted advisors (and a man who knew enough of courtly politics to keep his head low), Lord Audley, who converted the monastery into a home for his family.

It was his grandson, Thomas Howard, 1st Earl of Suffolk, who transformed the house into a splendid palace, quite literally fit for a king: in 1614 James I came for a visit. This Jacobean version of Audley End was one of the most ambitious building projects of its time. According to T.K. Cromwell in his Excursions in the County of Essex (vol. 1, 1818), the house

“was deemed equal to the palaces of Hampton Court, Nonsuch, and Richmond. […] Audley House, when first completed, consisted of various ranges of building, surrounding two quadrangular courts. That to the west was very spacious, and was approached through a grand entrance gateway, between four round towers.”

But such a vast palace was difficult to upkeep, and thus various wings and buildings were demolished in the course of the early 18th century as the house passed through various different branches of the Howard family (who had some problems producing an adequate number of heirs). It finally ended up in the possession of Elizabeth Griffin, Countess of Portsmouth, who bought the house in 1751 and had it remodelled and altered in the Jacobean style. While she didn’t have any children either, she solved that particular problem by naming her nephew as her heir on the condition that he change his surname to Griffin.

Not only did Sir John Griffin Griffin continue the alterations of the house, e.g. by having a new range of detached kitchen buildings erected on the north side of the house, but he also employed Capability Brown to transform the grounds around Audley End into a landscape garden, with buildings designed by Robert Adam. Alas, soon, Sir John and his garden architect quarelled bitterly—over the completion of the project (not on time) and added costs (way too high), but perhaps also because Sir John took a very decided interest in the remodelling and apparently wished to be very, very, very closely involved in it. The contract with Brown was eventually terminated, and the remodelling of the garden was entrusted to the otherwise unknown Joseph Hicks.

The grounds feature all the typical elements of a landscape garden: wide, sweeping views from the house with neo-classical follies acting as focal points, a stretch of water spanned by a neo-classical bridge, and a pleasing arrangement of various groups of trees.

However, in its current form, the house most closely reflects the taste of its owners in the 19th century, when once again due to the lack of a direct heir, the house passed to yet another branch of the family. And finally, in 1820, a nursery was established at Audley End. As the family of the 3rd Lord Baybrooke expanded, the nursery eventually moved to a larger set of rooms, which have recently been restored and opened to the public.

It was perhaps this nursery which surprised me most of all the things to see at Audley End: I had always thought of a nursery as a plain white-washed room, perhaps two, somewhere on the top floor of a great house. The nursery at Audley End not only consists of several rooms, but it is also large and comfortable with large windows that let in the light. There’s also a large doll house, filled with both bought items and homemade elements as is typical for dollhouses of this era. (Taking photos is forbidden inside the Audley End, hence no pretty pictures of the interiors.)

The nursery was run by a governess, who oversaw three nursery maids and, if necessary, a wet nurse. Mirabel, the eldest daughter of the house, loved doing watercolors, and apparently large parts of the nursery were restored based on her sketches and paintings. She never married, and remained life-long friends with her old governess. Richard, the eldest son of the family, had a keen interest in archaeology and taxidermy (with a special interest in birds). Today his fossils and stuffed birds (especially the stuffed birds) fill two galleries of the house and make you think you’ve accidentally stepped into a natural history museum.

While the displays in the big house focus on the family who lived here, the displays in the service areas and the stable block focus on the servants who worked here, with photographs of estate workers from the turn to the 20th century. And thus, a nice balance is achieved between “upstairs” and “downstairs.”

I went on a field trip yesterday with a bunch of museum/history geeks to

I went on a field trip yesterday with a bunch of museum/history geeks to  years after, which forms the core of the house. It’s possible to date it so accurately because dendochronology has determined that the cypress posts used in construction date to 1703. This extremely red room, apparently a highly popular color in the period, is the oldest part of the house. There’s a dark rectangle to the right of the notice on the door which is actually a hole cut in the woodwork to reveal the original cypress post.

years after, which forms the core of the house. It’s possible to date it so accurately because dendochronology has determined that the cypress posts used in construction date to 1703. This extremely red room, apparently a highly popular color in the period, is the oldest part of the house. There’s a dark rectangle to the right of the notice on the door which is actually a hole cut in the woodwork to reveal the original cypress post. Naturally subsequent owners began to make expansions and improvements, and suddenly, later in the century, Chinoiserie became all the rage. Hence this extraordinary staircase in the expansion of the house undertaken by George Plater III (lots of Georges in this family). He also became a governor of the State of Maryland, and, eew, I cannot get this out of my head: he married a 13 year old who had their first baby when she was 14, and who became, according to the Sotterly website, “a political and social asset to her husband.” Gawd.

Naturally subsequent owners began to make expansions and improvements, and suddenly, later in the century, Chinoiserie became all the rage. Hence this extraordinary staircase in the expansion of the house undertaken by George Plater III (lots of Georges in this family). He also became a governor of the State of Maryland, and, eew, I cannot get this out of my head: he married a 13 year old who had their first baby when she was 14, and who became, according to the Sotterly website, “a political and social asset to her husband.” Gawd. A pretty yellow parlor was added in this period and the shell alcoves in the room are original (built with help from Mt. Vernon’s slaves).

A pretty yellow parlor was added in this period and the shell alcoves in the room are original (built with help from Mt. Vernon’s slaves).