One of the topics under recent discussion was all the different types of gowns a Regency lady would have worn and how people could possibly have told the difference. Morning Gown, Domestic Costume, Walking Dress, Promenade Costume, Carriage Dress, all of these appear somewhat similar when you look at the period fashion plates, and you’re not wrong to be confused (and there’s a LOT of crossover).

The first thing to understand is that the name used for the fashion plates describes the activity being undertaken more than the garment being worn. The second thing to note is that often the most distinguishing factors are the accessories rather than the gown itself. The same basic white gown might have been worn for morning activities around the house and then with a quick change of accessories, been transformed into something to wear on a walk into the village or out to pay morning calls (which are more like afternoon calls in real life) if one was in Town.

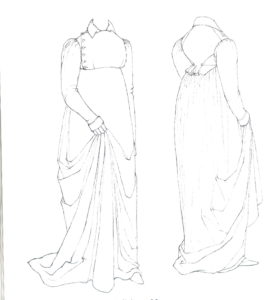

So let’s look at the prints themselves (these are all from Ackermann’s):

A domestic costume is exactly what it sounds like. Something informal and meant to be worn strictly indoors when at home. These are pretty much universally made of white linen fabrics and they’re gussied up with some kind of robe, pelerine, mantle, or shawl for warmth. These tend to be on the loose side, and were probably worn with jumps rather than stays. They’re also invariably shown with caps (roll out of bed, hair not done, probably still in curling rags, put your cap on). While your hero is having breakfast downstairs in his banyan, your heroine is having breakfast (probably in her room) in her Domestic Costume. In a family situation, the mother and elder girls might also be eating downstairs in this attire. And they might wear it all morning while they wrote letters, went over menus, etc.

When it came time to receive guests or to leave the house, she would change into a morning gown. Morning gowns are just a tad more formal than domestic costumes. So she’d likely put on her stays and have her hair arranged (though still in a cap!). Most of these outfits are shown with some kind of over garment, usually in the same fabric as the gown), and sometimes with gloves. This is the state in which she could come downstairs for a meal if there were guests or if she were a guest.

If she were walking into the village or going out to pay morning calls, she would swap out the simple over garment for a cloak, coat, spencer, etc., put a bonnet or hat over her cap, and maybe grab a muff or parasol depending on the time of year.

Promenade Dress. Note the halfboots, the veil, the watch and chain, the ridicule. She’s out to see and be SEEN! (and quite interestingly, NO HAT!)

A promenade costume is usually just a fancier update to accessories. It’s meant to be showy because you’re wearing it in the afternoon at the park or other location where fashionables went to see and be seen (you even see in the descriptions in Ackermann’s that the gown part of the “costume” is called a “morning gown”). And you pretty commonly see halfboots instead of slippers in the description and illustration.

So there you have it, your heroine might have changed costume four times today, or she might have just swapped around her accessories if she were frugal or not wealthy enough to have brought 50 gowns with her to a house party.