Susanna here!

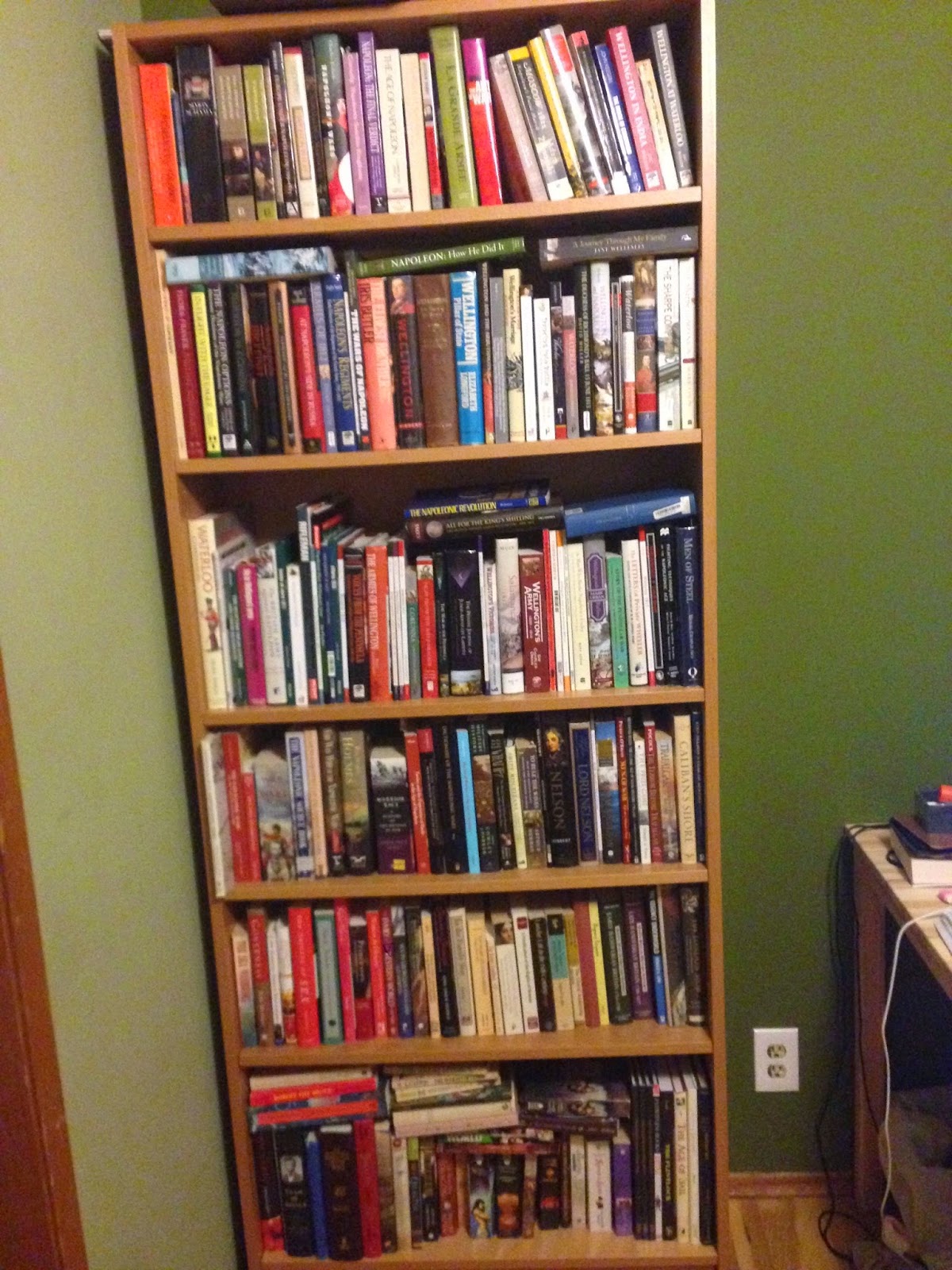

A week or two ago, I decided to count my to-be-read pile and discovered that between my Kindle and my bookshelves, I own over 300 unread books! Which is just crazy. I buy books faster than I read them, especially since I’m also getting books from the library that take precedence over the ones I own because I have to take them back in three weeks.

To lessen the madness a bit, I’ve decided that every third book I select to read has to come from the TBR. I don’t have to finish each book. I believe life is too short to waste time on books I don’t enjoy, so if I discover one of my impulse buys is poorly written, boring, annoying, or whatever and set it aside a chapter or two in, that still counts as clearing it.

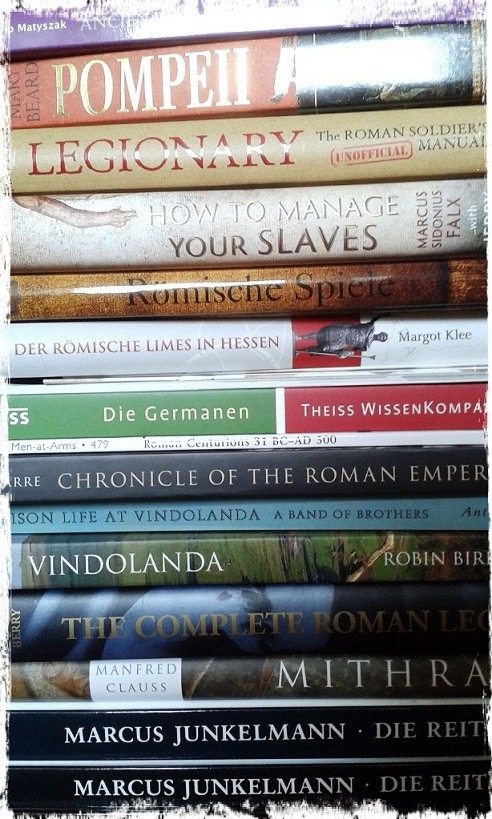

Almost a third of Mount TBR is composed of research books. I can’t walk through a used bookstore without checking out its history section and coming home with any likely-looking tomes on Wellington, Napoleon, the lives of women in the 18th and 19th centuries, and so on. And then there are all the times I’ve had an idea for a story, invested in some relevant research books, and for whatever reason either abandoned the idea or simply haven’t gotten around to writing it yet. So now I have all these books on Peninsular War battles like Salamanca and Busaco, on Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, and on Scottish Highland Travellers, just to name a few topics. Sometimes I swear those books are giving me reproachful looks for abandoning them to gather dust on my shelves.

So I decided that at least one and preferably two of my TBR books each month have to come from the research shelf. I just finished the first such book, The Regency Underworld, by Donald Low. It’s an overview of crime, police work, and punishment during the Regency, all the way up until London’s first modern police force was created in 1829. If you’re interested in those topics, it’s a quick, worthwhile read.

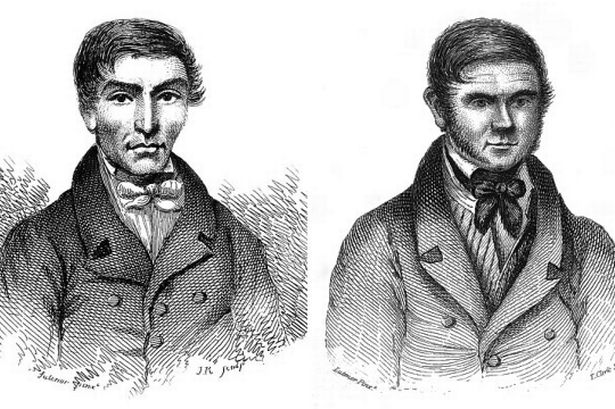

Most of the book focuses on London, but one incident in Edinburgh caught my eye–the Burke and Hare Murders of 1828. Burke and Hare became serial killers after hitting upon a gruesomely lucrative moneymaking scheme. A tenant in their lodging house died of natural causes while owing Hare and his wife rent money, so they decided to sell his corpse to the anatomists at Edinburgh University rather than turning it over for proper burial. You see, back then the only legitimate source for medical cadavers was executed criminals…but by the early 19th century the number of executions was declining while medical school enrollment was growing. This led to a literally underground business for “resurrection men” who’d sneak into graveyards at night, dig up fresh corpses, and sell them to anatomists (who turned carefully blind eyes to where their cadavers were coming from).

Once our villains saw that the medical school would pay good money and not ask many questions, it quickly occurred to them to make their own corpses…and in the year or so it took them to get caught, they claimed sixteen victims, largely by targeting those who weren’t likely to be missed. The public horror once the crimes were revealed was instrumental in the development and passage of the Anatomy Act of 1832, which was designed to expand the legitimate supply of medical cadavers.

This is all fascinating enough on its own account…AND it’s given me the early germ of an idea for a story. In my January release, Freedom to Love, my heroine has a 13-year-old half-sister who learned healing at her mother’s knee and wishes she could study medicine. By the time of the Burke and Hare Murders, she’d be 26. Who’s to say she wouldn’t be living in Edinburgh at that point, perhaps as the young widow of a doctor or apothecary? If she was, she’d spend as much time as a woman could around the medical community, and who knows what she might suspect or witness? I can’t guarantee this story will happen–see above about abandoned ideas!–but it’s certainly fun to play with.