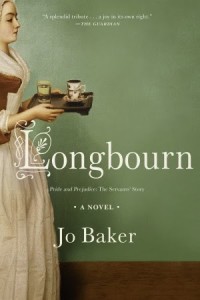

Have you read Jo Baker’s brilliant Longbourn? It’s the book that switches upstairs/downstairs in Pride & Prejudice so we get the story from the servants’ point of view. Because the servants are always there, and reading that book for me has now changed the way I read Austen.

Have you read Jo Baker’s brilliant Longbourn? It’s the book that switches upstairs/downstairs in Pride & Prejudice so we get the story from the servants’ point of view. Because the servants are always there, and reading that book for me has now changed the way I read Austen.

I’m giving a version of my talk on servants for JASNA in Minneapolis this weekend and so I’ve been sprucing up my material and  wondering whether or not to include the strange, wonderful, (slightly icky) story of Hannah Cullwick (1833-1909) and her master, Arthur Munby (1828-1910). Hannah wrote a diary, published in 1984 by Virago Press, UK (now out of print) that gives an extraordinarily detailed account of the everyday life of a Victorian servant.

wondering whether or not to include the strange, wonderful, (slightly icky) story of Hannah Cullwick (1833-1909) and her master, Arthur Munby (1828-1910). Hannah wrote a diary, published in 1984 by Virago Press, UK (now out of print) that gives an extraordinarily detailed account of the everyday life of a Victorian servant.

But it’s more than that.

Hannah wrote the diary at the instigation of her lover-employer-husband Arthur Mumby, who had a fetish for working class women and dirt, specifically women getting dirty. So a passage like this would get Arthur all hot and bothered:

Lighted the fire. Brush’d the grates. Clean’d the hall & steps & flags on my knees. Swept & dusted the rooms. Got breakfast up. Made the beds & emptied the slops. Cleaned & wash’d up…Cleaned the stairs & the pantry on my knees. Clean’d the knives & got dinner. Clean’d 3 pairs of boots. Clean’d away after dinner & began the preserving about ½ past 3 & kept on till 11, leaving off only to get the supper & have my tea…Went to bed very tired & dirty.

Boots, by the way, figure rather largely in their relationship.

Boots, by the way, figure rather largely in their relationship.

Hannah took great pride in her strength and endurance, choosing always to remain at the bottom of the Victorian servant food chain, as a maid of all work. A lawyer and amateur artist, poet, and anthropologist, Munby had a huge collection of photographs and other records of working women that he bequeathed to Trinity College Cambridge.

Hannah met Munby in 1854 and he followed her around from one position to another, watching her beat carpets and so on, and she was fired from at least one household because of his interest in her–this was a period, of course, when women servants were not allowed to have gentleman followers. Working at boarding houses rather than private houses gave her greater freedom. Eventually he hired her in 1872 and they married secretly the following year. But to all intents and purposes she was still his servant, and Munby’s friends–who included Ruskin, Rosetti, and Browning–had no idea of the true relationship, one that seems to have been classic BDSM.

For freedom & true lowliness, there’s nothing like being a maid of all work (1872)

She wore a locking chain around her neck, for which Munby had the key, and a leather strap on one wrist as a sign of his ownership. Munby posed her in various disguises–as a man, a chimney sweep, in blackface, as a fashionable lady.

She wore a locking chain around her neck, for which Munby had the key, and a leather strap on one wrist as a sign of his ownership. Munby posed her in various disguises–as a man, a chimney sweep, in blackface, as a fashionable lady.

But she had an extraordinarily strong sense of independence outside their fantasy life. She insisted, even after marriage, on receiving wages and keeping her own name, and she left him in 1877, although he continued to visit her, but presumably on her terms. You have to wonder who did wear the trousers in this relationship.

And that’s the question that seems to have plagued households, particularly during the Victorian period, when master-servant relationships seem to have escalated to an extraordinarily virulent level: who really is in charge here?

So at the moment, yes to Longbourn, and yes to Cullwick-Munby, and let’s see if anyone picks up on the subtext. And I expect they will, because smart readers of Austen always find the subtext.