Jenny Crusie has a great piece of advice for writers: “Don’t look down.” Meaning, don’t stop writing to worry about details or character arc or research.

I am not capable of following this advice. And I’m not saying it’s efficient, but it works for me: my writing is constantly enriched because I stopped to research. Scenes take fresh and exciting directions, I learn new things about my characters, and I understand more about the context in which the scene is taking place. I once stopped writing for two hours while trying to answer the question “Were there wastepaper baskets or equivalent in the Regency?” because my hero’s mother had to do something with her apple core. (Short answer: no, because very little was thrown away.)

While writing my current WIP (about a young woman who co-owns a gaming den with a 1790s theme), I’ve come across a startling number of amazing objects. So I thought I’d share ten supercool scraps of Regency and late–eighteenth century material culture with you this week!

(When links go to Pinterest, in most cases if you click again on the image, it will take you to the original website from which the image was pinned and you can read more about the item.)

1. Earrings in the shape of the guillotine, with Louis XIV’s head dangling underneath. 1790s.

2. In England, what we call “Solitaire” is called “Patience.” And it wasn’t really that popular yet in the Regency. What they called “Solitaire” was this lovely brain-teaser game with pegs. Researching this online is very difficult because it’s a big deal in game theory so all the websites are written by mathematicians, not historians. I found a website where I can play a virtual version, and it really is addictive!

3. Roulette was not yet played in England during the Regency (although it existed in France). Variants called roly-poly and E.O. (standing for Even and Odd) were, though. E.O. was originally designed in the 1730s to exploit a loophole in anti-gambling legislation, but was quickly outlawed itself. Despite that, it remained very popular! You can see an E.O. wheel here, and this 1786 Rowlandson engraving shows one in use.

“The W__st_r [Westminster] JUST-ASSES a Braying, or The downfall of the E.O. Table” by Gillray, 1782. This political cartoon presumably has something to do with gaming laws, but I don’t know what! The subtitle reads “NB: the Jack-Asses are to be indemnified for all the mischief they do, by the Bulls and Bears of the City.” Image via Wikimedia Commons.

4. Playing card decks are different throughout Europe! Did everyone know this but me? The deck we use in the States (52 cards, using hearts, clubs, spades and diamonds as suits) is the French deck. Spanish decks use the suits cups, coins, swords, and batons or sticks—familiar to me from Tarot decks! Furthermore, the pip cards only go to nine, so a full deck is 48 cards (or 50 with jokers), not 52. German decks use acorns, leaves, hearts and bells for their suits. So cute!

Portugal used to have their own pattern, but they switched to French decks sometime in the first half of the 20th century. (The transition left some idiosyncrasies; for example, the old face cards were King, Knight, and Page, but the pages were female! So “page” was mapped to “queen” on the new decks and many games rank the cards King-Jack-Queen.)

I tried especially to find examples of Portuguese decks and card games since my heroine is Portuguese. I haven’t found much yet except that the aces have dragons on them, and that modern Japanese karuta decks are based on decks brought by Portuguese traders in the 16th century. But I’ve got a request in to interlibrary loan…

Look at this great 19th century deck design.

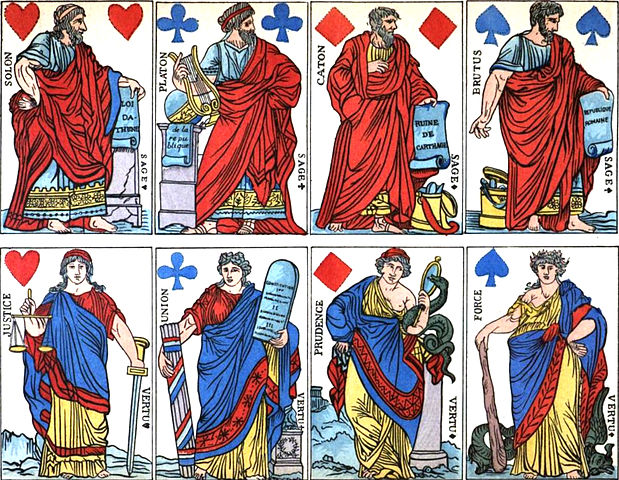

5. More cards: in Revolutionary France, it was pretty retro to use decks with court cards! New decks were designed, sans royalty. I found some beautiful examples, like this one where the court cards depict the Seasons, the four Elements, and some Revolutionary virtues!

Deck of Revolutionary cards, depicting great men (Solo, Plato, Cato, and Brutus) and the cardinal virtues. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

I also love this set (the queen of spades is a personnification of “Freedom of Marriage”, holding a sceptre labeled “Divorce”—divorce was briefly legal and widely available under the Revolution) and this one (in which the jacks are Republican citizens, the queens are the cardinal virtues, and the kings are philosophers)!

I almost bought this reproduction deck on Etsy until I realized I’d have to pay for shipping from France…

6. Another Regency card trend: transformation cards! The site links to many examples and explains: “Transformation Playing Cards are those in which the pip cards have been integrated into an overall design thereby ‘transforming’ the playing card into a miniature graphic artwork. The pips must retain their traditional position and shape, so it is sometimes difficult to create a good design. The idea became popular at the beginning of the 19th century as a pastime, when packs were often ‘transformed’ by hand using pen and ink.” It’s this transforming by hand that intrigues me most—wouldn’t that be a great scene or subplot in a romance? (Warning before clicking the link: racial caricatures.)

7. Regency folk did not use poker chips, but “fish”! Fish looked like little fish (no surprises there!) and were commonly carved out of ivory, bone, or mother of pearl.

8. Moving on from gambling, using a segue of stuff carved out of ivory: the renter of a box at the opera received six ivory tickets engraved with their box number and (sometimes? always? not sure) their name. They could give out (or sell) whichever of these tickets they weren’t using themselves to friends, which were good either for admission to their box or for seats in the pit. (I don’t totally understand the logistics of this ticket sharing, TBH, and two editions of the same traveler’s guide to London explain it differently.) Look, here’s one of the Duke of York’s 1804-5 season tickets!

9. This fan is some neat swag for subscribers to the boxes at the King’s Theatre (home of the Italian opera in London) for the 1787-88 seasons! Shows a floor plan of the boxes with subscribers’ names.

Speaking of useful information, some amazing opera fan to whom I am forever grateful kept a list of every opera performance (with dates!) at the King’s Theatre for the years 1801–1829, and published it! They include detailed information on the performers, performances, and backstage gossip (very opinionated information: “Another Catalani season, in which she sang every night except two; but in which, mirabile dictu, sterling good classical music prevailed in the ratio of 38 to 26”). This is the motherlode, OMG.

10. There’s nothing particularly special about it, I suppose, but there’s something about seeing this Regency parasol fold up just like a modern one that pleases me greatly. Be sure to click through to the V&A for more pictures and information about the telescoping handle and a Regency gadget shop called “Weeks’s Royal Mechanical Museum” (“This rather official title appears to be a purely commercial establishment; there is no evidence of royal patronage and items were for sale”).

Do you have a favorite Regency object?

Rose, I love this post! What very cool bits of material culture you found to share with us. I’m like you –I’ll stop to research, and love doing it, even though, as you say, it is not the efficient way to get a story finished! I once researched that same question about waste baskets, LOL. It’s details like that that really enrich a story for me (whether writing or reading). It sounds like we’ll have lots to learn from your new one. Does it have a working title yet?

Thanks! The working title is “Poker Story” because it’s based on the trope of the hero winning the heroine in a poker game. Not particularly inspiring, alas.

Rose:

So had to laugh at the story about wastepaper baskets. Did something similar recently regarding where people in London got water from…

Thanks for sharing all these lovely material culture links. Looking forward to reading your interpretation of the Regency gaming trope 🙂

Thank you! Water is one I still haven’t quite figured out…

What a fabulous post! Definitely a rabbit hole down which I could disappear for hours!

I adore those ivory opera tickets!

Thank you! Aren’t they lovely?? I really like the subscribers’ fan too.

Where’s the like/love/adore button?! So much fantastic information!

Aw, thank you!! One does one’s poor best. 😉

I had a moment much like your wastepaper basket one, wondering if people used paperweights during the Regency. Most of the elaborate ones I found were from later, so since my heroine was not wealthy but into science (what they called natural history) I had her keep a rock with a fossil in it on her desk and use it to keep loose papers from blowing away.

I’ve written a number of scenes on the chaise longue, so maybe that’s my favorite object.

http://www.mallettantiques.com/zh/a-regency-rosewood-chaise-longue