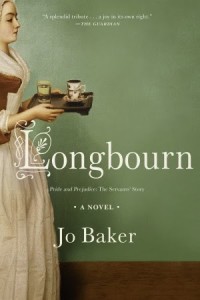

When the opportunity arose to sell my proposal for a Regency-set single title historical, Claimed By The Rogue, I jumped on it. For years I’d felt honor bound to provide a Happily Ever After for Lady Phoebe Tremont and her Mr. Robert Bellamy, two secondary characters from my very first book, A Rogue’s Pleasure.

When the opportunity arose to sell my proposal for a Regency-set single title historical, Claimed By The Rogue, I jumped on it. For years I’d felt honor bound to provide a Happily Ever After for Lady Phoebe Tremont and her Mr. Robert Bellamy, two secondary characters from my very first book, A Rogue’s Pleasure.

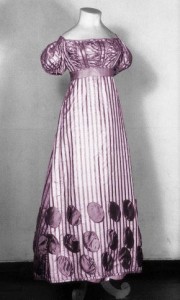

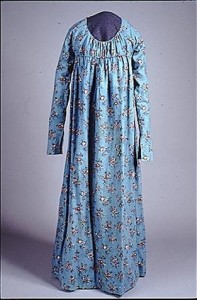

Doing so would mean rediscovering the Regency era, an historical period I hadn’t touched as a writer since 2000. My subsequent British-set historicals had all taken place in various other periods, notably the late Victorian. And for the past several years, I’d been far more focused on writing contemporaries. Adding to my anxiety was the Indisputable Truth: Regency romance readers are among the most knowledgeable Anglophiles on the planet.

Could I really pull this off?

More than a decade later as I immersed myself once more in Austen Land, reacquainting myself with foolscap and tuzzy-muzzies and the myriad rules of Almack’s, I came to a new and dare I say it, more “mature” appreciation of the Regency. In an age of “Blurred Lines” and “Bieber Fever,” slipping back into a society of grace and manners with clearly codified rules, not a blurred line among them, holds a certain undeniable appeal.

I also made several new-to-me discoveries. One of the more fascinating has to do with the London Foundling Hospital where my heroine, Lady Phoebe, volunteers as a school mistress–not so likely in the Regency Real World but fun to fictionalize.

Long before Charles Dickens’ works trumpeted the need to redress social and class injustices, a well off sea captain-cum-merchant by the name of Thomas Coram (1668-1751) noted the vast numbers of abandoned children living on the London streets and decided to do something about it.

Like so many visionaries, Coram did not have an easy go of it. He spent 17 years petitioning for the establishment of a hospital for “foundlings,” painstakingly bending the ears of the influential. On October 17, 1739, the Hanoverian King George II signed the charter incorporating the Hospital for the “maintenance and education of exposed and deserted young children.” The London Foundling Hospital was born.

The Hospital received its first orphans in 1741. Between 1742 and 1745, the handsome red brick building with stone facings that would serve as its permanent home into the 1920’s was built in Bloomsbury. The hospital continued as an orphanage until the 1950s when public opinion and British law shifted to home-based alternatives to institutionalization.

The Hospital received its first orphans in 1741. Between 1742 and 1745, the handsome red brick building with stone facings that would serve as its permanent home into the 1920’s was built in Bloomsbury. The hospital continued as an orphanage until the 1950s when public opinion and British law shifted to home-based alternatives to institutionalization.

In its early years, hospital policy governing admissions varied depending upon the degree to which Parliamentary funds were received. Initially only infants of up to twelve months of age were accepted. The child had to be deemed healthy and the mother unwed. Additionally, the child must be the fruit of the mother’s “first fall,” the belief being that surrendering her child would enable her to return to decency and make a fresh start.

On acceptance, children were sent to the countryside to be fostered. At four or five years of age, they were brought back to London and the Hospital, the girls to be trained for domestic service and the boys for a trade. Initially not only housing but also education was strictly sex-segregated, the boys and girls kept in separate wings.

From its onset, the Hospital attracted the patronage of the glitterati of the era, notably artists such as William Hogarth. one of the first governors. Hogarth donated several paintings to the Foundation including his handsome portrait of Coram, today displayed in the Foundling Hospital Museum’s permanent collection. Works by other great eighteenth century artists including Thomas Gainsborough and Sir Joshua Reynolds followed, festooning the walls of the elaborate Rococo-styled Governor’s Court Room. Small wonder that the London Foundling Hospital became the first art gallery open to the public.

Nor was patronage limited to visual artists. Handel permitted a benefit concert performance of his “Messiah” as well as donated the manuscript of the Hallelujah Chorus to the hospital. He also composed an anthem specially for a performance at the Hospital, now called “The Foundling Hospital Anthem.”

Alas, philanthropy in the eighteenth century was no more free from politics than are our contemporary institutions. Coram ran afoul of several of his fellow board members, who objected to his vocal criticisms. In 1741, he was ousted from the very institution he’d so selflessly created. Still, he continued his patronage, including weekly visits, until his death.

Happily Coram’s philanthropic legacy–and name-has more than borne time’s test. Today his charity, The Thomas Coram Foundation for Children, or simply Coram, continues, delivering services aimed at transforming the lives of underprivileged children.

A museum opened in 2004 on the site of the Hospital’s London headquarters at 40 Brunswick Square. It includes original eighteenth century interiors, furniture and fittings from the original London Hospital building including the Committee Room, the Picture Gallery, a staircase from the boys’ wing and the legendary Governors Court Room.

Perhaps most moving is the exhibit of foundling tokens–buttons, scraps of cloth and other everyday items–pinned by mothers to their baby’s clothes upon surrender. In the early days, children were baptized and renamed upon admission, so these simple tokens helped ensure correct identification, should a parent ever return to claim their child.

Perhaps most moving is the exhibit of foundling tokens–buttons, scraps of cloth and other everyday items–pinned by mothers to their baby’s clothes upon surrender. In the early days, children were baptized and renamed upon admission, so these simple tokens helped ensure correct identification, should a parent ever return to claim their child.

I hope to visit on my next trip to London. In the interim, much of the museum’s impressive programming and collections, including an absolutely fascinating project gathering the oral histories of former “orphans,” can be enjoyed online at its website: http://foundlingmuseum.org.uk.

Thanks to Megan Frampton and the other Riskies for having me here as a guest!

*Images courtesy of The London Foundling Hospital Museum.

Yesterday our guest Isobel Carr blogged in my place and today I’m taking Amanda’s place. Have we sufficiently confused you yet?? Maybe we’ve caught a fever and our brains are addled.

Yesterday our guest Isobel Carr blogged in my place and today I’m taking Amanda’s place. Have we sufficiently confused you yet?? Maybe we’ve caught a fever and our brains are addled.

When the opportunity arose to sell my proposal for a Regency-set single title historical,

When the opportunity arose to sell my proposal for a Regency-set single title historical,  The Hospital received its first orphans in 1741. Between 1742 and 1745, the handsome red brick building with stone facings that would serve as its permanent home into the 1920’s was built in Bloomsbury. The hospital continued as an orphanage until the 1950s when public opinion and British law shifted to home-based alternatives to institutionalization.

The Hospital received its first orphans in 1741. Between 1742 and 1745, the handsome red brick building with stone facings that would serve as its permanent home into the 1920’s was built in Bloomsbury. The hospital continued as an orphanage until the 1950s when public opinion and British law shifted to home-based alternatives to institutionalization. Perhaps most moving is the exhibit of foundling tokens–buttons, scraps of cloth and other everyday items–pinned by mothers to their baby’s clothes upon surrender. In the early days, children were baptized and renamed upon admission, so these simple tokens helped ensure correct identification, should a parent ever return to claim their child.

Perhaps most moving is the exhibit of foundling tokens–buttons, scraps of cloth and other everyday items–pinned by mothers to their baby’s clothes upon surrender. In the early days, children were baptized and renamed upon admission, so these simple tokens helped ensure correct identification, should a parent ever return to claim their child.