This is a repeat of a post from February 11 a few years ago, which was the birthday of William Fox Talbot (1800-1877) who is credited with being the inventor of photography.

This is a repeat of a post from February 11 a few years ago, which was the birthday of William Fox Talbot (1800-1877) who is credited with being the inventor of photography.

As with many scientific discoveries, the bits and pieces of evidence–optical and chemical–were lying around for some time, and it took an enquiring mind to put them together.

The optical side of photography was provided with the Camera Obscura, which had been around for centuries as an aid to drawing. Leonardo da Vinci used it, and his contemporary Daniel Barbaro described it thus:

Close all shutters and doors until no light enters the camera except through the lens, and opposite hold a piece of paper, which you move forward and backward until the scene appears in the sharpest detail. There on the paper you will see the whole view as it really is, with its distances, its colours and shadows and motion, the clouds, the water twinkling, the birds flying. By holding the paper steady you can trace the whole perspective with a pen, shade it and delicately colour it from nature.

An early sci-fi novel by Charles-Francois Tiphaigne de la Roche (1729-1774), Giphantie, predicted the invention of photography.

For centuries people had been aware that some colors bleach in the sun, but it wasn’t clear whether this was the effect of heat, air, or light. In the seventeenth century, Robert Boyle, a founder of the Royal Society, reported that silver chloride darkened with exposure. At the beginning of the nineteenth century Thomas Wedgwood of pottery fame experimented with capturing images but couldn’t make them permanent.

The first successful picture was made with an eight hour exposure by Joseph Niepce in 1827, using material that hardened on exposure to light–he named it a heliograph. Rejected by the Royal Society, Niepce went into partnership with Louis Daguerre, who reduced the exposure time to half an hour and discovered that salt stabilized the image, and invented the daguerrotype.

Interestingly, neither Niepce nor Fox Talbot could draw, which is why they were so interested in artificial means of producing images. Niepce was forced to look elsewhere to continue his interest in lithography when his artist son went to war in 1814 (and may have died at Waterloo–something I couldn’t confirm). Fox Talbot continued his own experiments, successfully producing his first photograph of the oriel window at Lacock Abbey,Wiltshire, in 1835.

Interestingly, neither Niepce nor Fox Talbot could draw, which is why they were so interested in artificial means of producing images. Niepce was forced to look elsewhere to continue his interest in lithography when his artist son went to war in 1814 (and may have died at Waterloo–something I couldn’t confirm). Fox Talbot continued his own experiments, successfully producing his first photograph of the oriel window at Lacock Abbey,Wiltshire, in 1835.

The photograph at the top of this post is also by Fox Talbot, showing Nelson’s column under construction in Trafalgar Square in 1843.

He nicknamed his cameras mousetraps.

He nicknamed his cameras mousetraps.

In 1844-46 he published a collection of photographs, The Pencil of Nature (get your mind out of the gutter), demonstrating that this technology had both artistic and practical possibilities–in inventorying possessions, creating likenesses, and possibly also being of use in the legal system. He reminded readers:

The plates of the present work are impressed by the agency of Light alone, without any aid whatever from the artist’s pencil. They are the sun-pictures themselves, and not, as some persons have imagined, engravings in imitation.

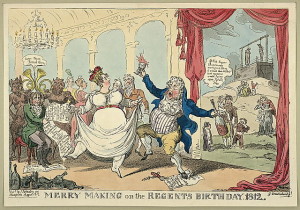

If Talbot Fox had been born earlier, or if he had been a particularly precocious teenager, we might have had photos of the Regency. So, the kickass question. Imagine you’ve gone back in time with your digital camera carefully concealed in your capacious muff or elegant reticule (or, okay, tucked inside your stays):

Who or what would you photograph?