Before we get into the lace-talk, I just wanted to alert those of you on Facebook to a new Regency group (I know, another one!) that has formed. Last week I was featured at Regency Kisses: Lady Catherine’s Salon (no, not THAT Lady Catherine!) and we went on a virtual/pictorial tour of England based on the settings in my books. Fun!

It’s an open group, although you have to join. We feature a different author each week, with giveaways and other entertaining activities. If you like this sort of thing, please consider checking us out. The “home” group of eight authors write “sweet with sizzle” Regencies, so if you like all heat levels, you might find some new-to-you authors to check out. Type the group name into the FB search bar and it should come up. Or, huh, I suppose I could be helpful and give you a link, eh? LOL. https://www.facebook.com/groups/LadyCatherinesSalon/

Please don’t go right now! We still want you to keep on being loyal readers of the Risky Regencies blog. We keep considering changing to some other format, maybe even a FB group, but many of you aren’t on FB and don’t want to be, either, and we respect that….

So, my most recent research rabbit hole has been lace. This time it wasn’t for a story, though. I thought I was going to need a new Regency gown. The Beau Monde Chapter of the Romance Writers of America is 25 years old this year, and we are celebrating at our conference in NYC in July! A gown for the Soiree is optional, but I’ve always worn a gown when attending such events, and since I am a founding member, this seems an unlikely year to suddenly stop doing so.

Through a friend, I recently acquired an entire bolt of beautiful lace, and another large chunk of a different lace, also beautiful.

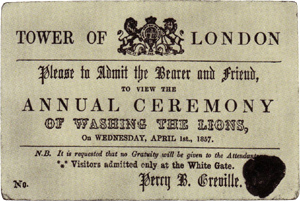

How pretty either one would be incorporated into a new Regency dress! I knew that the machines to produce English net dated to even before our period, and such net is often the base for lace designs, but when did they begin to be able to mimic hand-made lace with repeating patterns over a large area? I scoured through Ackermann’s prints, looking for dresses with full lace overskirts, and I quite naturally looked up the history of lace.

The introduction of machine-made net is quite well reflected in the styles of Regency gowns you can see in the fashion prints: net overdresses, sheer sleeves, etc. The machines, once refined, could even create patterns of intersecting strands and “spots” or stripes.

Ah, but actual patterned lace? That is a different thing altogether.

In our period, patterned lace was still made by hand, either using bobbins or various kinds of needlework techniques such as appliqué. You can find plenty of lace embellishment on gowns, but it is generally quite narrow, in bands or ruffled edges, because of the way it was made. Both needle and bobbin lace seem to have developed in Italy and Flanders during the early 16th century. Prior to that time, open-work decorative trims were made by cutting away and embroidering existing fabric. The new techniques created the openwork from threads, which could be linen, silk, gold or silver-bound silk, or much later, cotton.

The first machine lace was introduced in 1769, but the mesh raveled when cut. John Heathcoat developed a machine by 1809 that solved that issue and could produce “wide bobbin net”. But it wasn’t until 1837 that Heathcoat’s existing machine technology was successfully adapted (by Samuel Ferguson) to be able to produce a repeating pattern, as the jacquard machine looms could do. That is how the Victorians were able to have lovely lace curtains for their windows, and also makes sense of why they would, since it was a new and fashionable thing to have!

I could make a very pretty Regency gown using one of those laces I was given, but it wouldn’t be accurate, and that would always bother me. How would you feel? Even if I pretended the lace was all hand-done, I wouldn’t be comfortable, thinking of the huge amount of hours of poorly-paid labor that would have had to go into the making of it, if it were real. (I don’t think I know how to think like a super-wealthy aristocrat. Wouldn’t the lace-maker be grateful for my custom order and all that work?). Have any great alternative ideas for me to use all that lace?

In the meantime, it looks like I may be able to squeeze into my old dress, after all, with a few alterations. Here is a picture of me wearing it with Risky Elena, at the Beau Monde soiree back in 2003. (I do pretend the embroidery was hand-done. There’s a lot less of it!) I’ve worn it more recently than this photo, but not in years. I may not be able to move very much, LOL! Losing 25lbs would solve the problem, but I know that’s not going to happen! J

Needlelace: https://youtu.be/bNxdoB9dpkI and https://youtu.be/KXfR81nMlTU

Bobbin lace: https://youtu.be/YWQ-KZoePIo and https://youtu.be/E6kfb6FNVp8