You are invited to a tournament. In Scotland no less! There will be a few men in kilts, lots of people in medieval costume, knights in shining armor, and a multitude of shawls and bonnets that are, alas, neither waterproof nor color-proof. (Btw, you might want to bring an umbrella!!!)

“A tournament?” you might wonder. “Are we talking medieval romance now?”

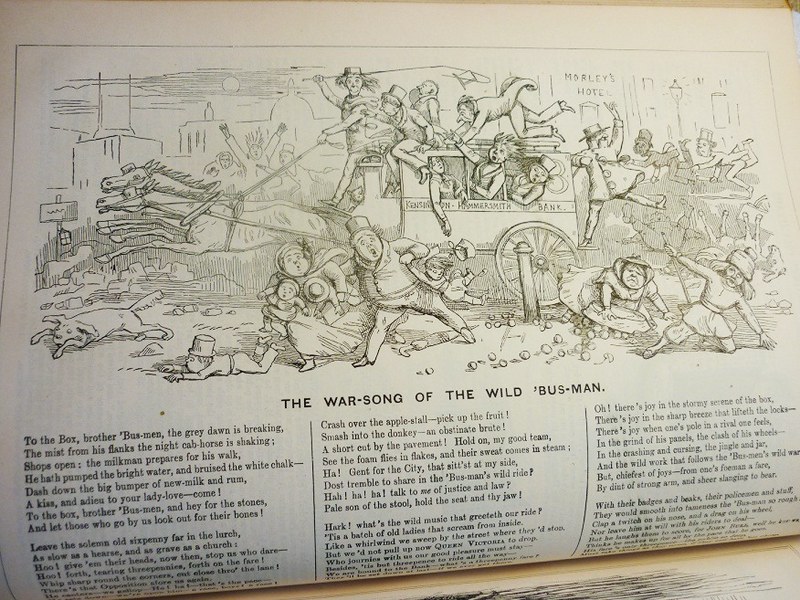

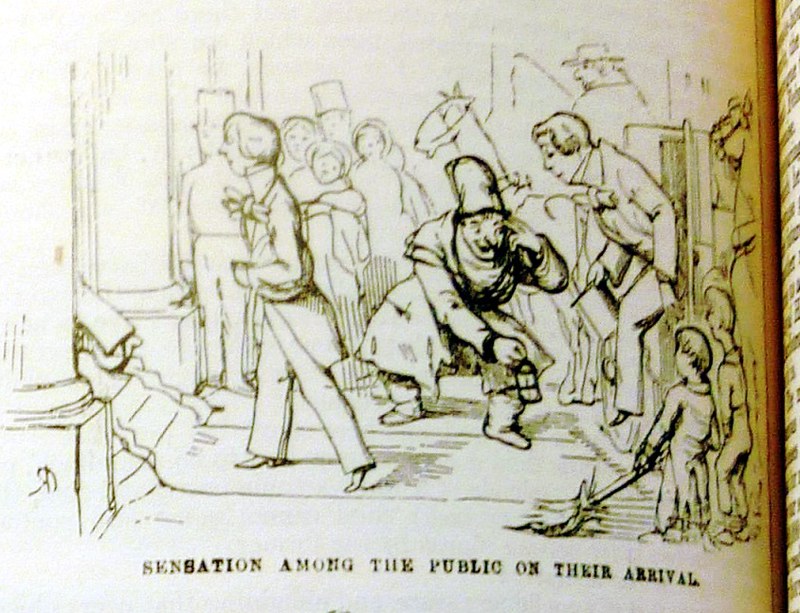

Nope. We are talking about a tournament in 1839. That summer ten thousands of people — ultra-conservative members of the British aristocracy and gentry as well as people from all around the world — flocked to Ayrshire in Scotland and overran several small, sleepy villages (the traffic jams in the area were dreadful and unlike anything anybody in Ayrshire had ever witnessed) in order to watch young Lord Eglinton’s medieval spectacle. He and some of his friends were to don medieval armor (commissioned from Messrs. Pratt in Bond Street, London) and joust like medieval knights. You know, just like the characters in Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe!

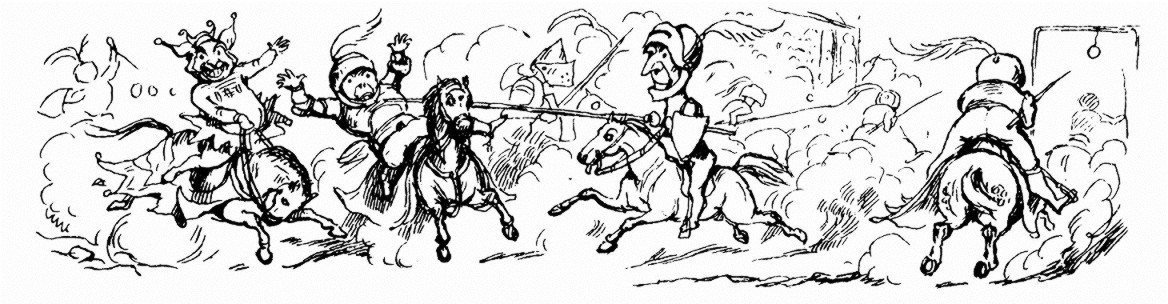

The noble knights had rehearsed for weeks in the garden of the Eyre Arms in St. John’s Wood (the “dress rehearsal” was watched by about 2000 people, which gives you some indication of the interest the tournament elicited), and they had given themselves proper chivalric names; names like The Knight of the Dragon (= the Marquis of Waterford) or The Knight of the Dolphin (= the Earl of Cassillis) or even The Knight of the Burning Tower (= Sir F. Hopkins). Lord Eglinton was Lord of the Tournament, and his stepfather Sir Charles Lamb acted as Knight Marshal of the Lists. As every tournament needs a Queen of Beauty to crown the victors, this role was given to Lady Seymour, who was allegedly one of the most beautiful women in all of Britain.

But why would anybody want to give a tournament in 1839?

But why would anybody want to give a tournament in 1839?

From the late 18th century onward, the Middle Ages had garnered new interest in Britain. The upper classes put medieval follies and fake ruins into their gardens or built themselves castles. Many of these neo-gothic buildings were invested with political symbolism, for medieval architecture became increasingly regarded as a symbol of Old England, where democracy was an unheard of thing. In addition, there was a flood of studies on all aspects of medieval life; portraits of people in medieval armor became all the rage; and Regency ladies amused themselves by painting medieval scenes on blinds.

But to spark the frenzy for all things medieval which emerged in the 19th century, it needed something more. It needed fiction written by an author who filled the imagination of his readers with images of noble knights and heroic deeds and whose imitators would feed and ever-growing audience with ever more glorious tales of the days of old when knights were bold. This author was Sir Walter Scott.

Numerous adaptations of Scott’s novels as well as his imitators increasingly presented audiences with an indealized version — a Disneyfied version, if you like — of the Middle Ages. The feudal age was transformed into a happy, glorious time when everybody knew their place and men were still men (hey, those knights fought against evil! and all kinds of monsters!! DRAGONS!!!!) and women stood helpless around, waiting to be rescued by a noble knight.

So when the old king died and a new queen was about to be crowned, everybody was looking forward to those age-old customs: the public state banquet for the Peers in Westminster Hall after the coronation service and that most wonderful ceremony of the King’s Champion riding into Westminster Hall and challenging all present to deny the queen’s right to the throne. It was going to be wonderful! Fabulous! And Sir Charles Lamb (Lord Eglinton’s stepfather) as Knight Marshal of the Royal Household was to marshal the Champion for Queen Victoria.

But then, alas, it was announced by the Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, that the young queen was to be crowned without antiquated medieval pomp and circumstance. There would be no banquet. No Queen’s Champion.

The Tories were incensed. There were protests in the House of Lords against this “Penny Coronation,” yet despite heated arguments, the Prime Minister stood firm. Poor Sir Charles and his whole family were utterly disappointed. To cheer Lord Eglinton up, one of his acquaintances suggested that he should add some kind of medieval party to the next annual private horse race at Eglinton Park. And soon a rumour spread like wildfire: Lord Eglinton was going to give a tournament at his country estate in Ayrshire! How romanti! How exciting! And because Lord Eglinton was a bit of a young fool, he finally announced that the rumour was true and thus embarked on what Ian Anstruther has called “the greatest folly of the century.”

——

You’ll hear more about the Eglinton Tournament next month when I’m going to launch a new series of novellas set in the early Victorian age. In the first story, THE BRIDE PRIZE, my hero and heroine are going to meet at the tournament. In medieval costume, of course, but sans umbrella, alas.