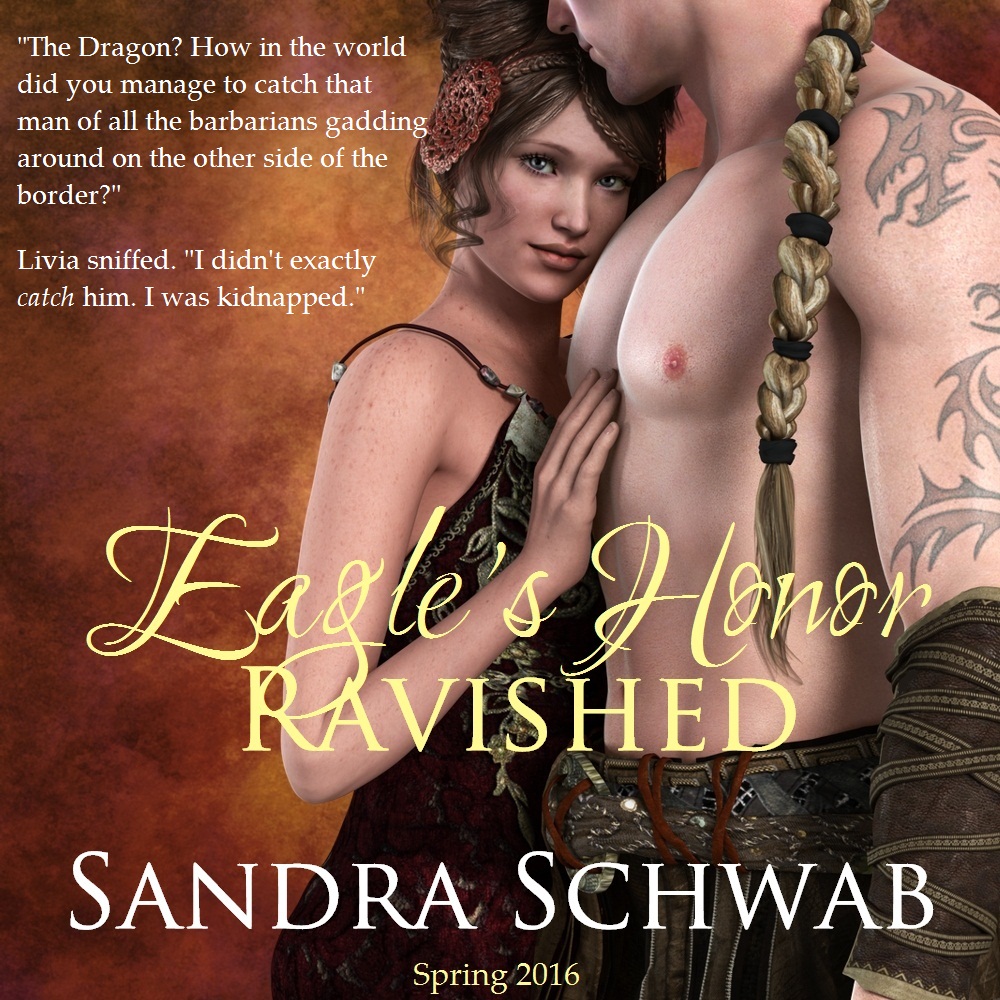

Hello Risky Readers, I’ve got so many exciting news for you this month! First of all, I’ll finally have a new book out: my second Roman romance will be ready for publication later this spring (I’m currently finishing up the revisions). Livia and Adelar’s story is set at the Germanic limes amidst heightening tensions along the borders of the Roman Empire.

I had a lot of fun with this story, not the least because it is set near where I live: I used the Saalburg, the reconstructed Roman fort I mentioned before, as the model for the fort commanded by my heroine’s uncle. I can tell you, it is most strange to stand onthe ramparts now and imagine that this was once the edge of an empire, the edge of what was regarded as the civilized world.

And remember that Roman cooking class I mentioned last month? That was also a bit strange and highly instructive! It also taught me a few things about myself as an author: I have a tendency to go for the weird stuff — in terms of Roman food this would be the fried dormice (sprinkled with poppy seeds), the sow’s udder stuffed with giant African snails, and, well, you get the idea. But of course, such dishes were the extreme, and, as I found out during that cookery class, “normal” Roman food tastes surprisingly… eh… normal. It’s a bit sweeter than what we are used to today because the Romans added honey or mulsum (white wine with honey and spices) to basically EVERYthing. But everything we made in that class was delicious, from the dates filled with walnuts and wrapped in bacon to the pork goulash with dried apricots (and a bottle of mulsum) to the chicken with mulsum and coriander. Yum!

As you can see from the picture above, we ate from replicas of Samian ware (pretty Roman earthenware) and with replicas of Roman spoons (smaller and more shallow than our own spoons). All in all, it was a most delightful afternoon and evening! And all for research! Wheee!

And my last bit of news? Well, as some of you know, my contract as a university lecturer ran out in December and was not renewed. And my chances to find a new job at another university are basically nil, so I needed to rethink my life and career options. Indeed, this whole year will be about rebuilding my life. At the beginning of April I laid the foundation for my new career: I’m now officially freelancing as a translator and cover designer! It’s super-thrilling and super-exciting and super-scary, but I hope I’ll be able to build a much happier life for myself as Sandra Schwab, author, artist, and translator. 🙂