Did they or did they not have chocolate sweets in the Regency period? (I have seen authors fight over this!) What kind of sweets DID they have? In my new book, Her Perfect Gentleman, the heroine conceives the idea (wisely or not) to involve much of the village of Little Macclow in a project to make sweets for the wedding everyone has come there to attend. Researching this part of the story was an interesting rabbit hole!

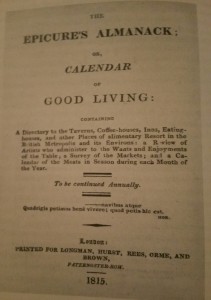

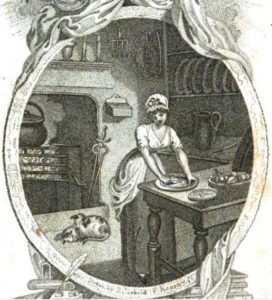

I found a great resource to help me, a “confectionary” cookbook from 1789 with newer editions in 1807 and 1809. It is called The Complete Confectioner (Or, the Whole Art of Confectionary with Receipts for Liqueures, Home-made Wines, etc. the Result of Many Years Experience with the Celebrated Negri and Witten, by Frederic Nutt, Esq.

I found a great resource to help me, a “confectionary” cookbook from 1789 with newer editions in 1807 and 1809. It is called The Complete Confectioner (Or, the Whole Art of Confectionary with Receipts for Liqueures, Home-made Wines, etc. the Result of Many Years Experience with the Celebrated Negri and Witten, by Frederic Nutt, Esq.

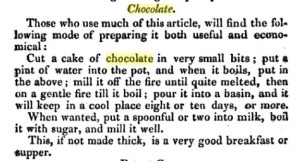

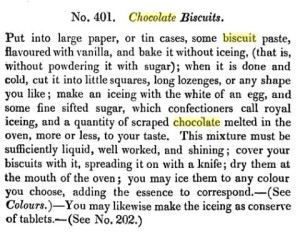

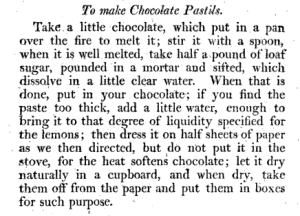

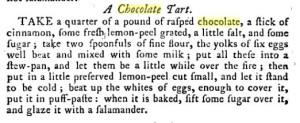

This remarkable tome (available in Google Books) includes 38 recipes for biscuits—that’s cookies, to us Americans—including chocolate ones made of chocolate, egg whites and powdered sugar, like meringues. No flour, which interests me to try them since I have allergies and must stay gluten-free.

There are also six types of wafers, and ten flavors of drops—including chocolate, so there WAS a type of chocolate candy in period, just not the kind we think of as “chocolates” today. Filled chocolate candies such as we eat today were first displayed to the world in 1851 at the Great Exhibition in London at the Crystal Palace, well past the Regency decades.

The Regency chocolate drops were just like the “chocolate nonpareils” you can still get today, named for the white sugar beads that coat them. Have you eaten chocolate nonpareils? Wikipedia says: “a round flat chocolate drop with the upper surface coated with nonpareils. Ferrero makes a variety marketed as Sno-Caps. In Australia, these confections are commonly known as “chocolate freckles“, or simply “freckles“. Nonpareils are also sold in the United Kingdom as “Jazzies“, “Jazzles“, “Jazz drops” and “Snowies” (the latter being of the white chocolate variety). The coating of nonpareils is often referred to as “hundreds and thousands” in South Africa and the UK. The Canadian company Mondoux sells them as “Yummies“. So if you want Regency sweets and don’t want to make them, buy yourself some of these!

The Regency chocolate drops were just like the “chocolate nonpareils” you can still get today, named for the white sugar beads that coat them. Have you eaten chocolate nonpareils? Wikipedia says: “a round flat chocolate drop with the upper surface coated with nonpareils. Ferrero makes a variety marketed as Sno-Caps. In Australia, these confections are commonly known as “chocolate freckles“, or simply “freckles“. Nonpareils are also sold in the United Kingdom as “Jazzies“, “Jazzles“, “Jazz drops” and “Snowies” (the latter being of the white chocolate variety). The coating of nonpareils is often referred to as “hundreds and thousands” in South Africa and the UK. The Canadian company Mondoux sells them as “Yummies“. So if you want Regency sweets and don’t want to make them, buy yourself some of these!

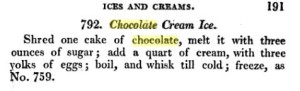

The book also covers eight kinds of jelly (and six jams), essences for ices, seventeen flavors of “waters” to serve at routs (including lemonade), 32 flavors of ice cream (including chocolate, but also “burnt almond” and “parmesan”), plus a whole section on “water ices” (I think similar to sherbert?), all sorts of fruits preserved in brandy, and a large section on preserved fruit both wet, candied, or dry. Beyond all this yumminess, Nutt also offers the promised recipes for liqueurs and wines, along with a small number of cakes and sweet puddings, plus illustrations for laying out a dessert course on tables for different numbers of guests.

Nutt’s book also has a whole section on “Prawlongs.” I read it with interest, having no idea what they were. I soon discovered other mentions spelled “prawlins” and guessed that perhaps it was an alternate spelling of pralines. According to an article on the history of the famous New Orleans pecan praline (here), the Praline is named after the 17th century French diplomat César duc de Choiseul, Comte du Plessis-Praslin (1598 or 1602-1675). One theory is that Plessis-Praslin’s personal chef Clement Lassagne was the actual inventor, and the sweets were gifts for the duc’s lovers. If you consider the French pronunciation of Praslin, I think Nutt’s spelling “prawlong” may have been phonetic.

These first pralines were made with a combination of caramel and almonds. However, Nutt’s recipes include pistachios, filberts, or almonds covered with caramelized sugar syrup, AND he also used the method with slivered lemon and orange peels, orange flowers, and chunks of Seville oranges!! So it may mean in the 18th century, at least in England, pralines (however you want to spell them) may have meant caramel-coated whatever-you-want! And the practical early settlers of New Orleans adapted the French recipe to pecans, since that’s what they had.

These first pralines were made with a combination of caramel and almonds. However, Nutt’s recipes include pistachios, filberts, or almonds covered with caramelized sugar syrup, AND he also used the method with slivered lemon and orange peels, orange flowers, and chunks of Seville oranges!! So it may mean in the 18th century, at least in England, pralines (however you want to spell them) may have meant caramel-coated whatever-you-want! And the practical early settlers of New Orleans adapted the French recipe to pecans, since that’s what they had.

I have to say, without the aid of candy thermometers that are so helpful for today’s cooks, I am in awe of how period cooks managed to turn out sweets without always burning the mixture or undercooking it. Would you be brave enough to try a recipe from 1809? Have you ever tried to recreate an authentic period dish?

Her Perfect Gentleman releases on Thursday (Dec 15th)! Can we wish my characters, Christopher and Honoria, a happy book birthday?