This week has been one of drama, tragedy, and protest following the death of George Floyd from the choke hold of a Minneapolis policeman. Floyd’s last words were, “I can’t breathe” and they became a rallying cry all over the nation and the world while thousands of people demonstrate to show, once and for all, that BLACK LIVES MATTER. To acknowledge this important piece of history in the making, I am going to tell about some Black lives in the Regency.

If you read our books, it is sometimes easy to imagine that the Regency was inhabited by a homogenous group of White people. That was not the case. Especially in the cities, the population was diverse. Some articles estimate as many as 15,000 Black people in England at that time. Most were servants, but they could also be tavern owners, tradespersons, businessmen, sailors, musicians–all walks of life.

Joseph Antonio Emidy, sold into slavery as a child, eventually became a virtuoso violinist who performed, taught music, and composed many works. He lived in Cornwall, had been married, and fathered eight children.

Dido Elizabeth Belle was the topic of the 2013 movie, Belle. Her mother had been a slave; her father, the son of a baronet. As a baby, her care was entrusted to her uncle, the 1st Earl of Mansfield and she was brought up as a member of the family and inherited enough money from the earl to see to her comfort for life. The earl’s will also specifically documented her freedom. She married a Frenchman who might have been a gentleman’s steward. They had two sons.

William Davidson was the natural son of the Attorney General of Jamaica and a Black woman. At 14 he traveled to Scotland to study law, but after being apprenticed to a Glasgow lawyer, he was press-ganged into the Royal Navy. After his discharge, he started a cabinet making business which eventually failed. He eventually became involved in radical politics and was one of the Cato Street conspirators. He was executed for that crime.

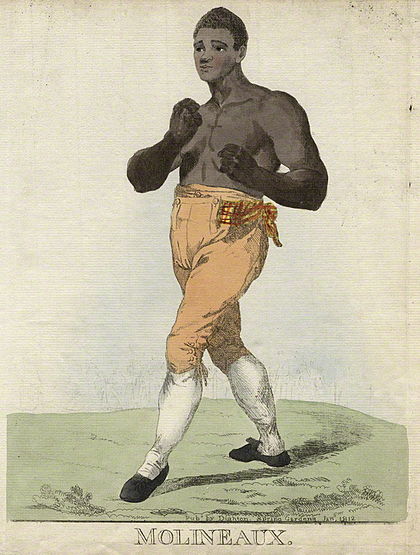

Tom Molineaux and Bill Richmond were both former slaves who had success as professional boxers.

Cesar Picton was enslaved from Africa at about 6 years old. He became an exotic page boy to Sir John Phillips a baronet and became a favorite of the family. With a legacy of one hundred pounds from Lady Phillips, Picton set himself up in business as a coal merchant. He became wealthy and died a gentleman.

These are only a few of the diverse Black people who lived during “our” time. I found several examples of others. Most were once slaves or were born to slaves, but against great odds developed successful lives and deserve their place in history.