Diane here, posting for Amanda whose WordPress is doing wonky things. Here’s Amanda!

I’m so happy to be back at the Riskies today! I hope I can still be considered a part-time (or honorary) Risky). I’m also so excited to have the chance to talk a bit about the history behind the book for my new release The Queen’s Christmas Summons. This story has been brewing in my mind for a long time, ever since I was a little girl and my grandmother (who was very proud to be Irish, and have the famous “black Irish” looks of dark hair, olive skin, and bright blue eyes) told me she was descended from a shipwrecked Spanish soldier who landed on Ireland’s coast in a storm and married a Galway woman. This story, while fantastic, is almost certainly a family legend, but it made me wonder—what would really happen if two such people met??? That’s how John (an English spy planted with the Armada) and his love Alys came to be. She saves his life on the Irish shore—and they meet up later at the queen’s own court for Christmas.

I’m so happy to be back at the Riskies today! I hope I can still be considered a part-time (or honorary) Risky). I’m also so excited to have the chance to talk a bit about the history behind the book for my new release The Queen’s Christmas Summons. This story has been brewing in my mind for a long time, ever since I was a little girl and my grandmother (who was very proud to be Irish, and have the famous “black Irish” looks of dark hair, olive skin, and bright blue eyes) told me she was descended from a shipwrecked Spanish soldier who landed on Ireland’s coast in a storm and married a Galway woman. This story, while fantastic, is almost certainly a family legend, but it made me wonder—what would really happen if two such people met??? That’s how John (an English spy planted with the Armada) and his love Alys came to be. She saves his life on the Irish shore—and they meet up later at the queen’s own court for Christmas.

I’ll be giving away a signed copy of The Queen’s Christmas Summons to one lucky commenter, chosen at random.

The paperback is available now at bookstores and online venues. The ebook will be released November 1.

The Spanish Armada (Grande y Felicisima Armada, “great and most fortunate navy”) was one of the most dramatic episodes of the reign of Elizabeth I, and one of her defining moments. If it had succeeded, the future of England would have been very different indeed, but luckily, weather, Spanish underpreparedness, and the skill of the English navy were on the queen’s side. The mission to overthrow Elizabeth, re-establish Catholicism in England, and stop English interference in the Spanish Low Countries, was thwarted.

King Philip began preparing his invasion force as early as 1584, with big plans for his fleet to meet up with the Duke of Parma in the Low Countries, ferry his armies to England, and invade. His first choice as commander was the experienced Marquis of Santa Cruz, but when Santa Cruz died Philip ordered the Duke of Medina Sedonia to take command of the fleet. The Duke was an experienced warrior – on land. He had no naval background, and no interest in leading the Armada, as the invasion fleet came to be called. He begged to be dismissed, but Philip ignored the request, as well as many other good pieces of advice about adequate supplies and modernizing his ships.

After many delays, the Armada set sail from Lisbon in April 1588 (in The Queen’s Christmas Summons, it carries my hero, an English spy, along with it!). The fleet numbered over 130 ships, making it by far the greatest naval fleet of its age. According to Spanish records, 30,493 men sailed with the Armada, the vast majority of them soldiers. A closer look, however, reveals that this “Invincible Armada” was not quite so well armed as it might seem. Many of the Spanish vessels were converted merchant ships, better suited to carrying cargo than engaging in warfare at sea. They were broad and heavy, and could not maneuver quickly under sail. The English navy, recently modernized under the watch of Drake and Hawkins, was made up of sleek, fast ships, pared down and easy to bring about, which would prove crucial.

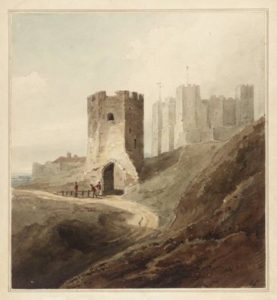

A series of signal beacons atop hills along the English and Welsh coasts were manned. When the Spanish ships were at last sighted off The Lizard on July 19, 1588, the beacons were lit, speeding the news throughout the realm. The English ships slipped out of their harbor at Plymouth and, under cover of darkness, managed to get behind the Spanish fleet. When the Spanish finally reached Calais, they were met by a collection of English vessels under the command of Lord Howard.

The English set fireships adrift, using the tide to carry the blazing vessels into the massed Spanish fleet. Although the Spanish were prepared for this tactic and quickly slipped anchor, there were some losses and inevitable confusion. On Monday, July 29, the two fleets met in battle off Gravelines. The English emerged victorious, although the Spanish losses were not great; only three ships were reported sunk, one captured, and four more ran aground. Nevertheless, the Duke of Medina Sedonia determined that the Armada must return to Spain. The English blocked the Channel, so the only route open was north around the tip of Scotland, and down the coast of Ireland. Storms scattered the Spanish ships, resulting in heavy losses.

By the time the tattered Armada regained Spain, it had lost half its ships and three-quarters of its men, leaving a fascinating trove of maritime archaeological sights along the Irish coast (and myths of dark-eyed children born to Irish women and rescued Spanish sailors! In reality, most of them met fates far more grim and sad). Among this most unlikely of places, John and Alys meet and find love!

Did any of this history of the Armada surprise you? Remember to leave a comment about the Armada or about The Queen’s Christmas Summons for a chance to win a signed copy!

If you’d like to read more about this fascinating time, here are a few sources I liked:

Robert Milne-Tyne, Armada!, 1988

Ken Douglas, The Downfall of the Spanish Armada in Ireland, 2009

Neil Hanson, The Confident Hope of a Miracle: The True History of the Spanish Armada, 2003

Laurence Flanagan, Ireland’s Armada Legacy, 1988

James Hardiman, The History of the Town and Country of Galway, 1820

Colin Martin, Shipwrecks of the Spanish Armada, 2001

Garrett Mattingly, The Armada, 1959