I asked in a reader group what topics people were interested in having covered on blogs these days and got a whole list of things that I’ll be tackling in the coming months, but the one that seemed the most fun right off that bat was ridicules/reticules.

When hoops were worn and skirts were full, it was easy for a woman to carry about her sovereign purse, pines, etc. in her pockets. These were large, easy to access through the “slits” formed in the top of the petticoats by their being fashioned as a double-apron. But when the round gown became a thing at the end of the 18th century, pockets were no longer feasible. So what was a lady to do? She still needed to carry a few things with her as she went about. The earliest ridicule I’ve seen looks very much like a single pocket. Which makes perfect sense. You’d just tie the waist ties together to form a loop/handle and carry it with you (fashion historians often surmise that this is where the original name “ridicule” came from, as it women were ridiculed for carrying about their pocket).

The Victorian and Albert Museum has quite a collection of these, and all the images I’m sharing today are from their archive (I’m noting this as per their user agreement). As always, click for a larger copy of the image.

Classic set of pockets. These were tied around the waist, over the stays and underskirts, but beneath the top petticoat (aka the lady’s skirt).

18thC embroidered Pockets (photo credit: Victorian and Albert Museum).

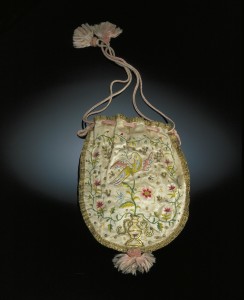

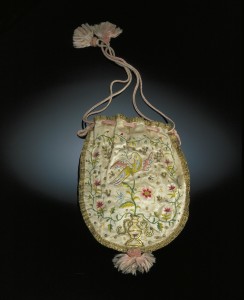

This first bag is transitional, it retains the rough shape of a pocket, but has a drawstring at the top. It’s beautifully embroidered with flowers and a bird, most likely done by the woman herself as the embroidery does not appear professional in quality.

Silk, embroidered with silk thread, with string tassel and straps. c.1790-1800 (photo credit: Victorian and Albert Museum).

The museum didn’t give much information about this little bag, but I love the hedgehog styling of the knit dags.

Knit bag, c. 1800 (photo credit: Victorian and Albert Museum).

Netting was a popular pastime, and it’s possible these bags were made by the woman who used them. The smaller red bag is a “finger-ring purse”, the perfect thing for a lady who just needed enough money on her for vails or small purchases.

Netted silk and thread, with hinged gilt frame, 19thC (photo credit: Victorian and Albert Museum).

This is a very basic square purse with absolutely amazing ribbon embroidery.

Embroidered silk satin with chenille thread, appliquéd with silk muslin, lined with silk taffeta. c. 1820-1830 (photo credit: Victorian and Albert Museum).

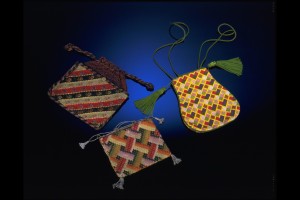

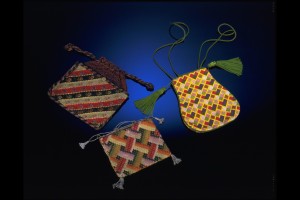

Wool embroidery on canvas (basically needlepoint) bags. This was another common pastime. You see everything from slippers to purses to pocketbooks (wallets) to fire screens worked this way.

Canvas, embroidered with wool. 19th. (photo credit: Victorian and Albert Museum).

Candice Hern also has a lovely collection that’s worth perusing if you haven’t already. She has everything from small beaded sovereign purses, to larger netting reticules and even miser purses of the kind a man might carry in his coattail pocket.

Thanks to Eileen for the question!