I’ve heard quite a few people say that patchwork quilting is an “American thing” and came out of the Civil War. I have no idea where this comes from, but I’m here to tell you that patchwork quilts were a thing in the Regency (they would probably have called them “pieced coverlets”). In fact, Jane Austen, her sister Cassandra, and their mother made an absolutely gorgeous patchwork quilt that is on display at Chawton. It’s made in the English paper piecing method (where you sew each bit of fabric around a paper form and then join all the little bits together with whipstitches before removing the paper).

Per the Jane Austen Museum, in May 1811, Jane wrote to her sister Cassandra, “have you remembered to collect pieces for the Patchwork? — we are now at a standstill.” The quilt uses 64 different fabrics for the hundreds diamond shaped squares, and many of them are “fancy cut” to show off the design to its fullest. If you’re a quilter and feeling like a real challenge, you can get a free copy of the pattern to recreate Jane’s quilt here.

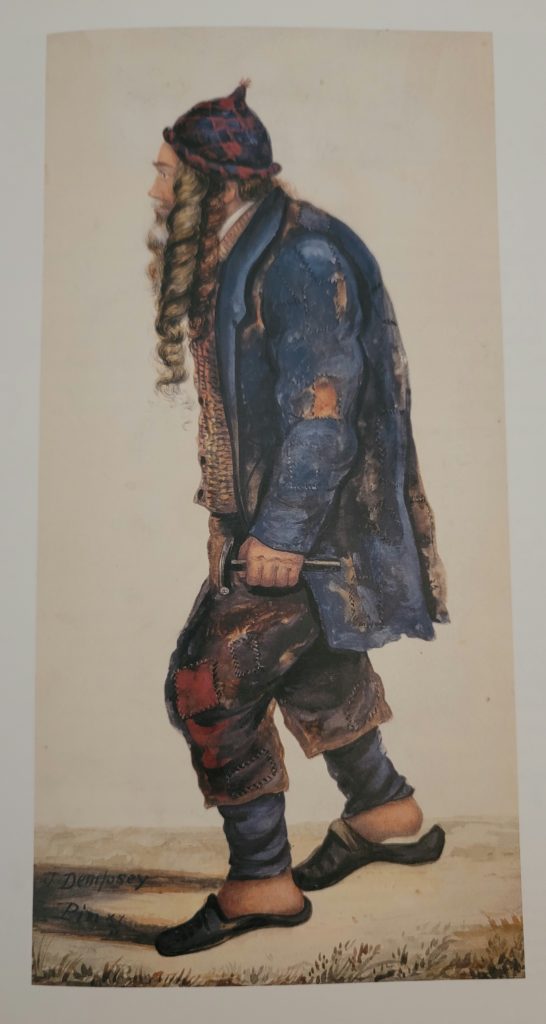

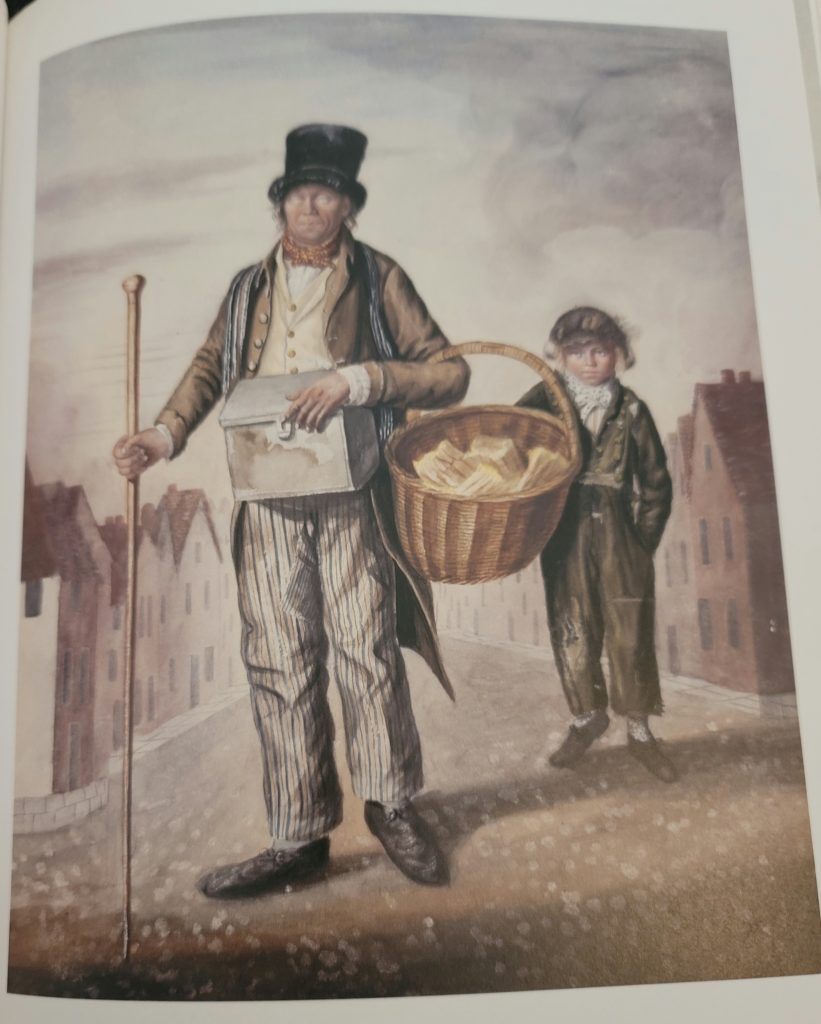

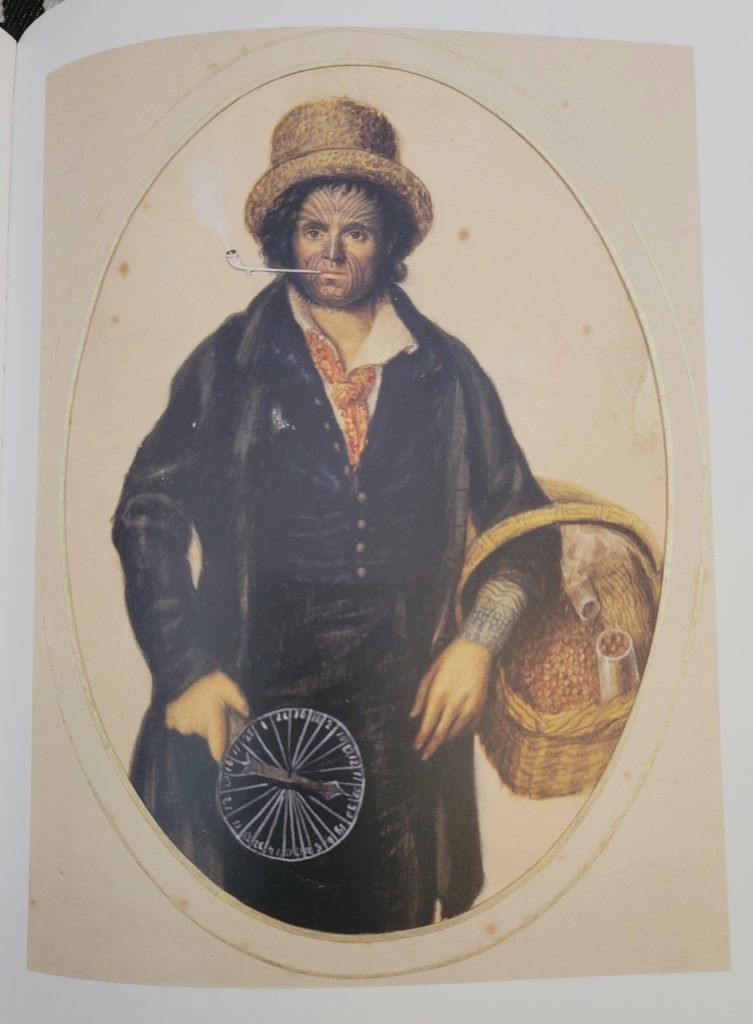

And quilting/piecing wasn’t limited to furnishings. I think most of us are familiar with matelasse quilted coverlets (whole-cloth quilts) and with the 18th century petticoats that were made in the same fashion. But there are also examples of pieced clothing. Like this absolutely amazing banyan (images are Open Access from The MET).

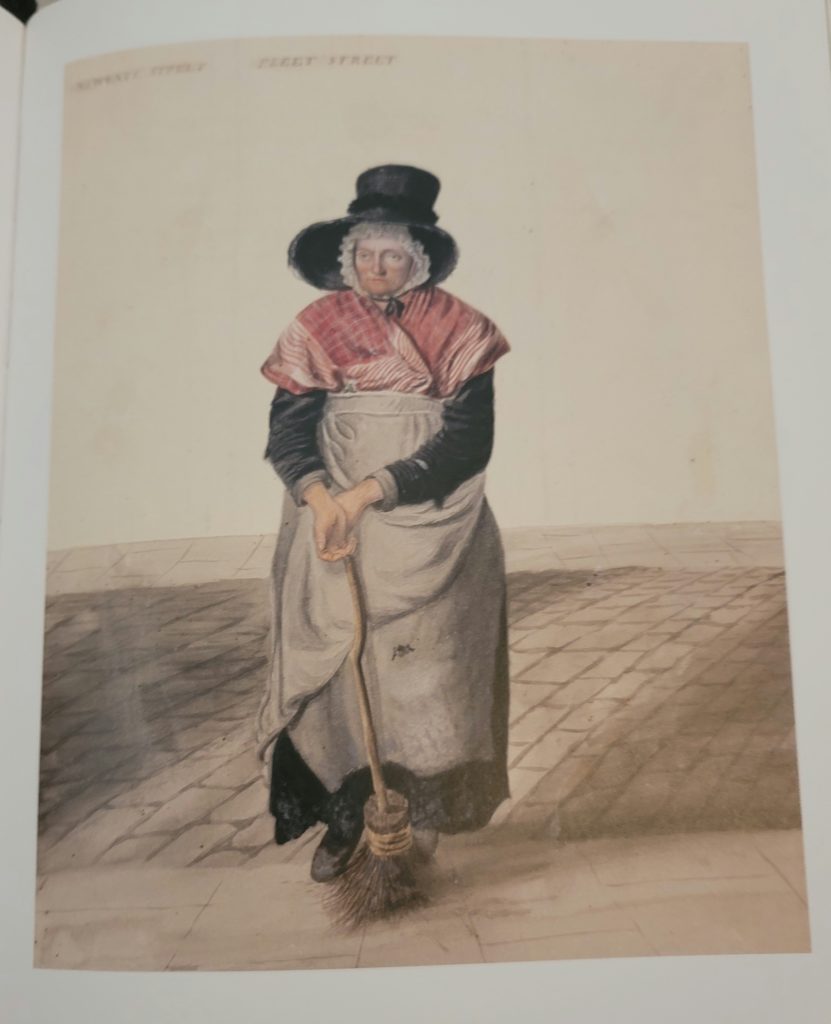

I’ve been doing a little quilting lately, myself. Nothing as ambitious as Jane’s quilt, but fun and pretty. I recently finished this one in a fabric called “Whimsical Romance” for my friend Jess (the artist who does my covers, and who is busy right now getting the new covers for my Ripe series ready). The parts that look white are actually text from A Midsummer’s Night Dream.