I have the unfortunate habit of getting rather obsessed with minor points of research – like travel. When I wrote my second novel, Castle of the Wolf, I spent at least a week if not more (probably more given that I have a fat folder full of notes and research material) reading up on travels on the Rhine. I pushed the date of the story back several years in order to make it feasible that my heroine would take one of the early steamships for traveling to the south of Germany. Indeed, I even unearthed timetables for the steamers that transported people up and down the Rhine.

And all of this for not even half a chapter. Wheee!

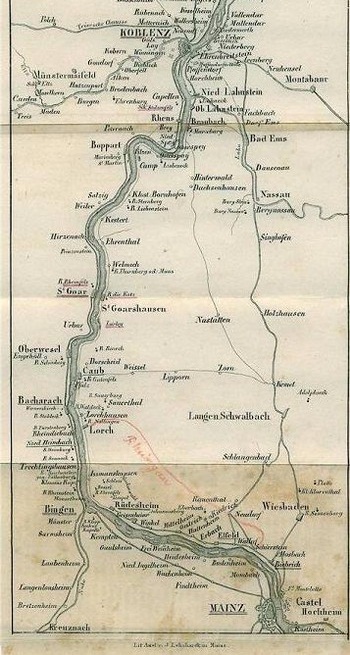

(On the left you can see a part of a map of the Rhine that was included in the third edition of Baedeker’s guide book Die Rheinreise from 1839. You can view the whole map here.)

In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the ease with which people were able to travel was, of course, largely dependent on their income. Indeed, most people would have never traveled far from home: just as far as their feet could carry them. Hiking tours were apparently quite popular among students, and in the 1790s it was one such tour – a trip of the two friends Ludwig Tieck and Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder through southern Germany – that brought about the birth of German Romanticism.

In Britain meanwhile, the eastablishment of a network of turnpike roads in the 18th century improved travel considerably. Turnpike roads opened up the countryside and made the country estates of the aristocracy and the gentry more accessible. Various new forms of passenger transport came into being, with the fastest form of transport being the mail coach (they didn’t have to stop at toll gates, and horses were changed frequently), followed by stage coaches, which could carry up to 18 people. Moreover, several inns specialized in the renting of post coaches and horses to wealthier travelers. Yet the cost for carriages, horses, and toll fees made traveling still expensive.

Thus, perceptions of distances could vary widely as the following conversation between Lizzie and Mr. Darcy from Austen’s Pride and Prejudice shows (from Chapter 32; they’re at the Collinses’):

“It must be very agreeable to [Mrs. Collins] to be settled within so easy a distance of her own family and friends.”

“An easy distance do you call it? It is nearly fifty miles.”

“And what is fifty miles of good road? Little more than half a day’s journey. Yes, I call it a very easy distance.”

“I should never have considered the distance as one of the advantages of the match,” cried Elizabeth. “I should never have said Mrs. Collins was settled near her family.”

“It is a proof of your own attachment to Hertfordshire. Any thing beyond the very neighbourhood of Longbourn, I suppose, would appear far.”

As he spoke there was a sort of smile, which Elizabeth fancied she understood; he must be supposing her to be thinking of Jane and Netherfield, and she blushed as she answered,

“I do not mean to say that a woman may not be settled too near her family. The far and the near must be relative, and depend on many varying circumstances. Where there is fortune to make the expence of travelling unimportant, distance becomes no evil. But that is not the case here. Mr. and Mrs. Collins have a comfortable income, but not such a one as will allow of frequent journeys — and I am persuaded my friend would not call herself near her family under less than half the present distance.”

(Hmmm…. It might be time for another re-read of Pride & Prejudice.)

When I dug into travel in Roman times this weekend, I was quite surprised to find a number of parallels to Georgian and Regency England: not only do several of the major roads in Britain (and in other parts of Europe) still follow old Roman routes even today, but along the Roman roads you could also find a network of inns and way stations. Ideally, every 6 to 12 Roman miles you would have had a way station, where you could change horses, and every 25 Roman miles an inn where you could spend the night. 25 Roman miles, approximately 37 km or 23 modern miles, was probably meant to be the distance somebody walking on foot could cover in a day.

Many of these stations were meant to be used by traveling officials or by merchants transporting goods like fabrics or building material. They could change horses for free and could also spend the night at the inns for free. The costs had to be covered by the local towns and communities, which led to many tensions between the provinces and Rome.

But what perhaps surprised me most was the fact that maps were already available in Roman times: they listed all the towns along the chosen route and also gave the distances between towns. Here is a snippet from one such map, the Tabula Peutingeriana from 250 (from a facsimile from 1887/88; the whole map can be found here):