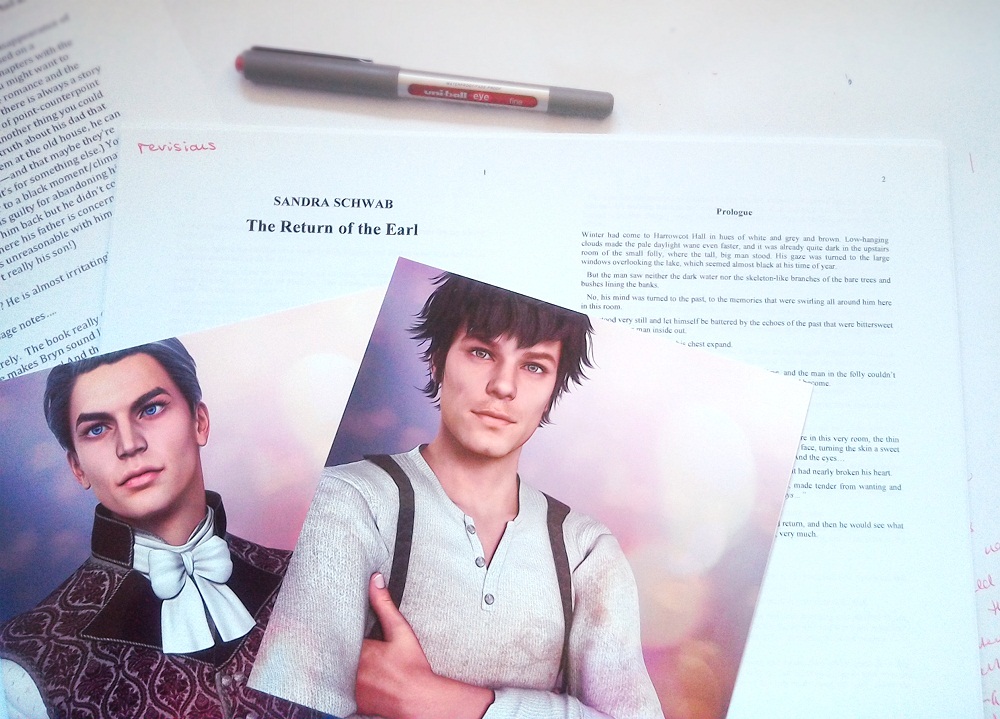

First of all: Oh my gosh, I’m so sorry I forgot to post yesterday! I was busy putting the finishing touches to Yuletide Truce, one of my Victorian holiday stories, which will be released later this year, so I’d be able to send it to my beta readers. I did send it to my beta readers last night (and of course, I’m now convinced they’ll hate me after reading the manuscript) (but hey, that’s a vast improvement over thinking my manuscript might prove fatal for my poor editor!!!)

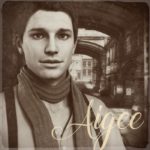

Aigee (short for Alan Garmond), one of the main characters in Yuletide Truce, has grown up in one of the poorest districts of London, before he was apprenticed to a bookseller at age eleven. He is torn between his new life and his old, and he often returns to his childhood haunts.

Aigee (short for Alan Garmond), one of the main characters in Yuletide Truce, has grown up in one of the poorest districts of London, before he was apprenticed to a bookseller at age eleven. He is torn between his new life and his old, and he often returns to his childhood haunts.

So, not surprisingly, for this story, I looked at some of the darker aspects of Victorian London, and one book in particular proved to be enormously helpful in finding out about the poorer population: Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor.

Mayhew was one of the co-founders of Punch (yes, we always come back to Punch, don’t we *grins*), though he severed the ties with the magazine only four years later. In 1849, the editors of another periodical, The Morning Chronicle, invited him to write a series about the working people of London under the title of “Labour and the Poor.” These articles formed the basis for an extended three-volume study, namely London Labour and the London Poor.

Henry Mayhew, from Wikipedia

Mayhew’s work is in many ways ground-breaking — not just because he threw light on a class of people who were so often forgotten, but also because interviews made up the bulk of his articles. Through him we get to hear the voices of the streetsellers, the old-clothes dealers, the mudlarks, the omnibus drivers, and chimney sweeps. He let them talk about their jobs, their everyday lives, their hopes and dreams. One of the streetsellers Mayhew introduces is the muffin man:

“The street sellers of muffins and crumpets rank among the old street-tradesmen. It is difficult to estimate their numbers, but they were computed for me at 500, during the winter months. They are for the most part boys, young men, or old men, and some of them infirm. […]

I did not hear of any street seller who made the muffins or crumpets he vended. […] The muffins are bought of the bakers, and at prices to leave a profit of 4d. in 1s. […] The muffin-man carries his delicacies in a basket, wherein they are well sweathed in flanne, to retain the heat: ‘People like them war, sir,’ an old man told me, ‘to satisfy theym they’re fresh, and they almost always are fresh; but it can’t matter so much about their being warm, as they have to be toasted again: I only wish good butter as a sight cheaper, and that would make the muffins go. Butter’s half the battle.’

A sharp London lad of fourteen, whose father had been a journeyman baker, and whose mother (a widow) kept a small chandler’s shop, gave me the following account:

‘I turns out with muffins and crumpets, sir, in October, and continues until it gets well into the spring, according to the weather. I carries a fustrate article; werry much so. If you was to taste ’em, sir, you’d say the same. […] If there’s any unsold, a coffee-shop gets them cheap, and puts ’em off cheap again next morning. My best customers is genteel houses, ’cause I sells a genteel thing. I likes wet days best, ’cause there’s werry respectable ladies what don’t keep a servant, and they buys to save themselves going out. We’re a great conwenience to the ladies, sir — a great conwenience to them as likes a slap-up tea. […]'”

(Can somebody pass me a warm muffin, now, please?) (And we’re talking English muffins, of course, a type of small, flat, round bread, rather than the cake-like American muffins.)