“Mom?” asked Miss Fraser, age 8. “How’s the writing going?”

“Pretty good,” I replied. “Rose had some ideas for putting more conflict in my Christmas novella, so I’m working on fitting those into the story.”

“What do you mean, conflict?”

“You know–all the bad things and problems that make a book interesting, that the characters have to work through to get to the happy ending.”

“Oh.” She frowned thoughtfully. “I have a good idea. You could put an earthquake in the story.”

“Well, that would be exciting, only the story is set in England, and they almost never have earthquakes there.”

Miss Fraser shrugged and gave me a look that said, Do I have to do EVERYTHING for you? “Then put in something they DO have.”

I then tried to explain about internal conflict and all the baggage my hero and heroine have left over from when they last met five years before, but her eyes started to glaze over. Miss Fraser thinks my stories sadly lacking in wizards, Greek gods, and clans of warrior cats going on quests.

A few days later I got into a conversation with my husband about how sometimes problems are easier to solve than you think. I had a character in my aforementioned Christmas novella whose existence was critical to my other characters’ lives, so I couldn’t just write him out altogether. But he had nothing interesting to do within the few days of my plot, and having him around was pulling focus off the characters who DID matter.

At first I was stumped, but then I came up with a simple solution: I changed my atmospheric Christmas Eve snow flurries to a wind-driven storm that accumulated thickly, and I made my extraneous character’s wife heavily pregnant instead of halfway through her second trimester. Voila! Now Harry the Necessary but Uninteresting wouldn’t dare venture on the roads and risk having his firstborn delivered in a carriage mired in a snowdrift, and all was right with my fictional world.

Mr. Fraser wasn’t so easily satisfied. “What are you going to do when some reader comes after you with an almanac proving it didn’t snow that Christmas Eve?”

I shrugged.

“You don’t CARE, do you?” he asked, eyebrows climbing in indignation. (I should note here that Mr. Fraser is a bit of a weather geek. As a child his dream career was meteorologist.)

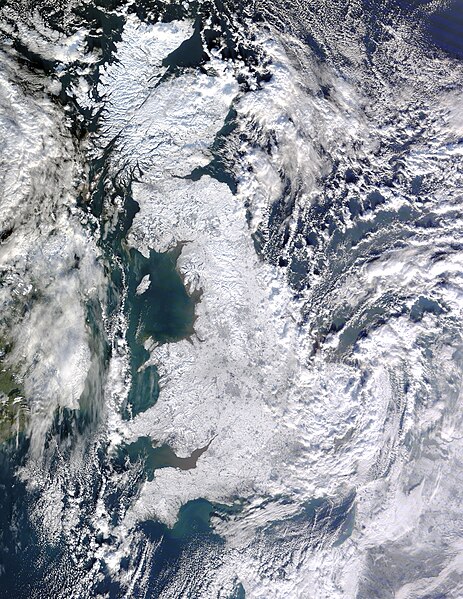

“Look, I’m all about historical accuracy–to a point. I wouldn’t write Waterloo without the big rainstorm the day before, since it had a huge impact on the outcome of the battle, or forget that 1816 was the Year Without a Summer. But looking up the exact weather of every single day is several levels of obsessiveness beyond where I’m willing to go. Besides, this is a CHRISTMAS STORY. A white Christmas is a TROPE. It snows in England NOW. No one is going to have trouble believing in a Christmas snowstorm in 1810–especially given that the more of a weather geek they are, the more likely they are to know about the Little Ice Age and how much colder it was back then.”

“But what if 1810-11 was the warmest winter on record? What if it’s the year everyone talked about the daffodils blooming in January and all the young rakehells swimming naked in the Thames on Christmas morning?”

“Hmph. Unlikely.”

“Hmph. Where is your story set, exactly?”

“Kent.”

Mr. Fraser opened a new browser tab for Google and searched for weather in Kent in 1810. When nothing much came up, he searched on London and found a bit of data, but nothing that specifically remarked on Christmas. Peering over his shoulder, I spotted a reference to the Thames freezing over in January 1811. “Ha!” said I. “I stand by my story.”

“But what if it was a sudden cold snap?”

“I don’t CARE. A white Christmas is a TROPE.”

I hope you’ve enjoyed this glimpse of living a writer’s life in House Fraser. Does your family give you helpful advice whether you ask for it or not? And where do you draw the line between accuracy and obsessiveness?