Today marks the anniversary of the first Luddite riot. Chambers Book of Days calls it “a black-letter day in the annals of Nottinghamshire.”

Today marks the anniversary of the first Luddite riot. Chambers Book of Days calls it “a black-letter day in the annals of Nottinghamshire.”

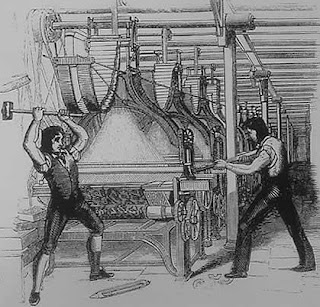

Luddites were stocking knitters and wool croppers in Nottingham, Yorkshire, Lancashire, Leicestershire and Derbyshire, who were trying to save their livelihoods by smashing the machines that replaced them. They were against being replaced by low-skilled workers. They wanted their fair pay. They also wanted an end to inferior products created by machine which undermined the reputation of their craft.

On March 11, 1811, the first Luddites destroyed sixty-three knitting frames, sparking a series of such incidents that spanned over about 6 years.

No one knows for certain where the name Luddites came from. It is said to have originated from an apprentice weaver named Ludd who smashed his loom in anger at the master who beat him. Or, less dramatically, The Book of Days says a youth named Ludlam who when his framework-knitter father told him to “square his needles” took his hammer and smashed them.

No one knows for certain where the name Luddites came from. It is said to have originated from an apprentice weaver named Ludd who smashed his loom in anger at the master who beat him. Or, less dramatically, The Book of Days says a youth named Ludlam who when his framework-knitter father told him to “square his needles” took his hammer and smashed them.

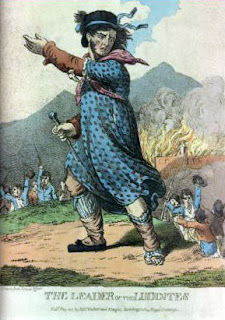

However the name originated, the leaders of the rioting against the industrialization of their craft came to be called General Ludd or King Ludd, and the character became as legendary as Robin Hood.

The government refused to step in to aid the Luddites (in spite of Lord Byron speaking in their behalf in Parliament). They focussed on enforcement, but, because the Luddites disguised themselves and because their communities were so tightly unified with them, most were never caught and punished. Basically the rioters and protesters, the machine smashers, were all desperate enough to risk hanging or transportation.

Eventually enough machines were destroyed and enough manufacturers were willing to cede to the Luddites wishes that the movement lost some steam. Even though some Luddite leaders joined other movements for social change. By 1817 frame smashing ceased to become an issue.

Today we still use the term Luddite to refer to any opponent of industrial change or innovation.

I can’t say I’m an opponent of industrial innovation, but I sure can’t figure out how to use all the features on my Smart TV!

In what way are you a Luddite? Or, if not you, do you know a Luddite?

(by the way, I’ll pick Sally MacKenzie’s winner after 12 midnight tonight)