It’s Mycroft’s “gotcha” month, and in honor of my current beast, I thought I’d talk about Mastiffs during the Georgian era. I grew up with Newfoundlands, Great Danes (aka Boar Hounds) and Irish Wolfhounds (all period breeds for my Georgian characters, though Wolfhounds and their cousins the Scottish Deerhounds were exceedingly rare during this period). I absolutely adore big dogs, the bigger the better.

I lucked into a copy of The Complete Dog-Fancier’s Companion; describing the Nature, Habits, Properties &c. of Sporting, Fancy, and other Dogs from 1819 a few years ago. It talks about various breeds, instructions for rearing, training, and basic care (the veterinary advice is quite frightening), and has an amazing rant about the evils of blood sports that ends with: For the sake of humanity, it is to be hoped, that the cruelty exercised on the animal, had- been repented of by his master, the greater brute of the two [emphasis in original], and that there are none at present who could be guilty of a similar outrage.

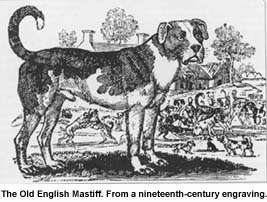

One of the breeds featured is the Mastiff. Now, you know I’m prejudiced, as I own one, but they truly are magnificent dogs. My first book, Lord Sin/Sin Incarnate, featured an Italian mastiff (a Neapolitan in modern terms) named Caesar. Ripe for Pleasure (which I just got the rights back to, and will be re-releasing with a new cover!), features a mongrel mastiff or butcher’s dog (basically a Bullmastiff) that was inspired by my sister’s dog, Slag and my best friend’s dog, Talullah (both littermates of my first Mastiff, Clancy).

Here is what the magazine has to say about Mastiffs:

The mastiff is much larger than the bull-dog, and every way formed for the important trust of guarding and securing the valuable property committed to his care. Houses, gardens, yards &c. are safe from depredations whilst in his keeping. Contained during the day, as soon as the gates are locked, he is left to range at full liberty: he then goes round the premises, examines every part of the them, and by loud barkings, gives notice that he is ready to defend his charge.

Well, my boy sleeps all night (ok, he sleeps most of the day too, LOL), but he does snap-to at the slightest hint of intrusion or danger and I’ve no doubt that he’d defend me and his “turf” if there was ever a need to do so (and let me tell you, the UPS man and the occasional religious evangelists are in no doubt of this either; though now that Jorge the UPS man has been introduced he no longer gets anything more than a tail-wagging hello through the window).

Much of what the author of my little magazine says elsewhere is surprising either for its prescience or its enduing common sense. At one point he notes that people commonly suppose dogs to be the civilized descendants of wolves! Remember this is 1819, before Darwin’s Origin of the Species. Under the training section the author advises: When you correct him to keep him in awe, do it rather with words than blows . . . When he hath done any thing to your mind and pleasure, you must reward him with a piece of bread. Sounds just like puppy training class to me, LOL!

Another book published in 1800, the Cynographia Britannica, said about the breed:

What the Lion is to the Cat the Mastiff is to the Dog, the noblest of the family; he stands alone, and all others sink before him. His courage does not exceed his temper and generosity, and in attachment he equals the kindest of his race.

I’m simply drawn to these giant dogs like no other I’ve ever encountered, and after owning one of my own, I can’t imagine ever owning anything else (ok, I can imagine owning most giant breeds, but they’re basically a type of mastiff or a mastiff spin off).

I certainly find my love for them popping up in my books. I need to branch out and give the people in my next book something else . . . I can see some kind of coach dog for them maybe (aka a Dalmation). And someday, I’ll write someone a cat…