This ice-encased lamp by my front door started me on this trip down the rabbit hole, which has nothing (so far) to do with any of my current writing projects. The two-inch-thick ice gave the light shining bravely through it a beautiful glow, and admiring it, I thought, “Thanks for electricity! This couldn’t have happened during the Regency.” Well, at least not without considerable effort to melt, chip, or break through the ice, since the lamp would have needed to be lit.

This ice-encased lamp by my front door started me on this trip down the rabbit hole, which has nothing (so far) to do with any of my current writing projects. The two-inch-thick ice gave the light shining bravely through it a beautiful glow, and admiring it, I thought, “Thanks for electricity! This couldn’t have happened during the Regency.” Well, at least not without considerable effort to melt, chip, or break through the ice, since the lamp would have needed to be lit.

That made me think about who would have had to do it, and lamplighters in general, and street lighting, and how in the Regency the transition from oil street lights to gas was actually a Big Deal that I’ve never seen mentioned in any of our novels. (Have you?) It’s just one more way the Regency era was the dawn of the modern age. Gas street lights were still in use into the 20th century, and there are still some in London. (I’ll come back to this!)

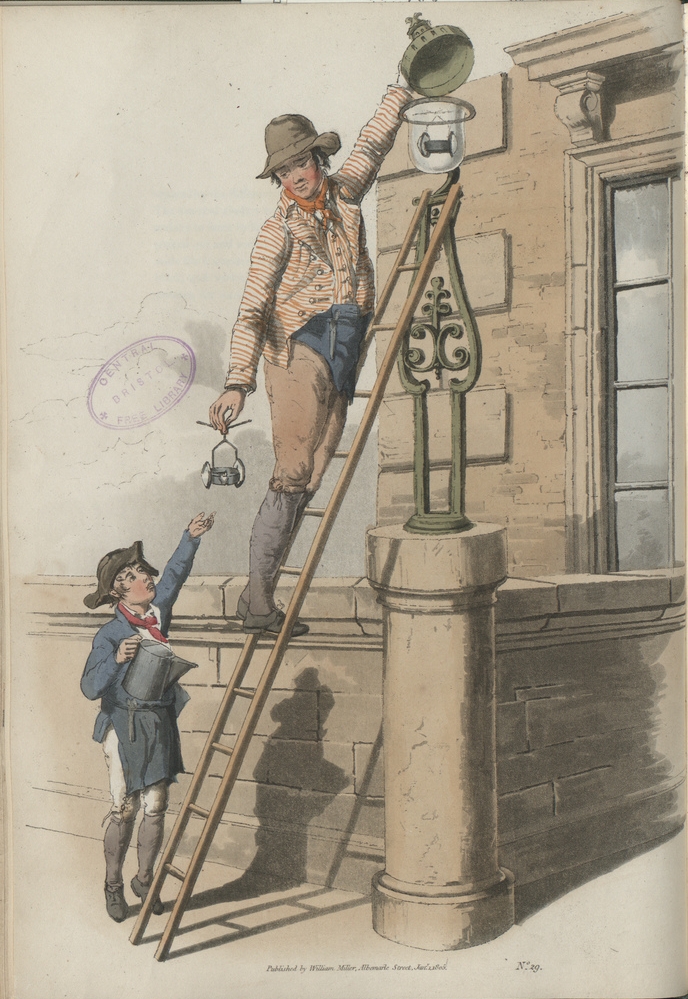

Our busy London characters never seem to run into any lamplighters, yet an army of them were out there at dusk every evening, with their ladders and long poles, making sure that the city was alight for the busy evening of activities ahead. And in homes that fronted along streets, someone had to light the exterior lamps every night, no matter the weather. (Doesn’t that make you start to appreciate the simple flipping of a switch?)  Prior to the introduction of street lighting (and in rural areas), nighttime excursions depended entirely upon the moon or light you provided for yourself, that traveled with you, plus the light from houses along your route. I ran across a reference to some regulations that required homeowners to provide lights, at their own expense, so it wasn’t just a courtesy! Light you provided yourself might have been a portable lantern, or lamps on your carriage, or even a hired “link boy” who would carry a torch to light your way safely (if he wasn’t in league with a group of thieves). Hmm, that could be fun….

Prior to the introduction of street lighting (and in rural areas), nighttime excursions depended entirely upon the moon or light you provided for yourself, that traveled with you, plus the light from houses along your route. I ran across a reference to some regulations that required homeowners to provide lights, at their own expense, so it wasn’t just a courtesy! Light you provided yourself might have been a portable lantern, or lamps on your carriage, or even a hired “link boy” who would carry a torch to light your way safely (if he wasn’t in league with a group of thieves). Hmm, that could be fun….

The system of oil street lamps in London and major towns was put into place starting in 1750, so the major changes in city life that came with such improvements –the reduction of crime, improved personal safety, and the glittering array of late night entertainments our characters enjoy: at theaters, pleasure gardens, private balls, assemblies, gambling hells, or even extended shopping hours– had become the norm only within a generation or two of our Regency characters. Travelers to London were suitably impressed, sharing descriptions like this in their writings: “In Oxford Road alone there are more lamps than in all the city of Paris. Even the great roads, for seven or eight miles round, are crowded with them, which makes the effect exceedingly grand.” – Archenholtz, 1780s

The next big thing, the introduction of gas lighting, did not happen easily, even though gas burned much brighter than oil. As I dove into this topic, I quickly found I had 11 printed pages of notes!! This is what happens –most of you reading this are research junkies, too, so you understand. LOL. Even my attempt at a brief timeline came out too long to put here — there’s so much fascinating stuff!!

The next big thing, the introduction of gas lighting, did not happen easily, even though gas burned much brighter than oil. As I dove into this topic, I quickly found I had 11 printed pages of notes!! This is what happens –most of you reading this are research junkies, too, so you understand. LOL. Even my attempt at a brief timeline came out too long to put here — there’s so much fascinating stuff!!

So, the short(er) version:

After the discovery of natural coal-gas in mines and its flammability, people began experimenting. In 1739 Dr. John Clayton first manufactured coal gas by heating coal placed in a small retort. More experiments followed. In 1792, William Murdoch, a Scottish mechanical engineer and inventor who worked with steam engines in Cornwall for the firm of Boulton and Watt, and who had been experimenting with practical uses for coal gas, set up a retort in his own home in Redruth, Cornwall, laid pipes, and lit all of his house and workshop with gas, the first to achieve this.

Murdoch went on to become the manager of Boulton and Watt’s steam engine works in Soho, Birmingham, where he used gas to light the main building of the Soho Foundry in 1798. In 1802, Murdoch lit the outside front of the building by gas, to the astonishment of the gathered locals. Boulton and Watt began making gas retorts and pipes, and sent Murdoch to fit up many of the big cotton mills in the North with the new lights (which enabled extended working hours, for better or worse!). Murdoch later went on to invent other useful items, but that’s another story.

Other people were also pursuing the prospects for using gas. Frederic Albert Winsor, a German, came to London with knowledge of a French patent for piping gas. Despite little knowledge of chemistry or engineering, Winsor claimed to be an authority on gas and pursued his ultimate aim of lighting the streets of London. He wanted Parliament to set up a national gas company. Samuel Clegg, a fellow employee (or a student? or both?) of Murdoch’s at Boulton and Watt headed to London, where he apparently teamed up with Winsor, for he is named as one of the founders of the company Winsor eventually succeeded in starting.

1803 — Winsor gave a demonstration of lighting the Lyceum Theatre in the Strand with gas.

1804 – Winsor began to give public lectures about the uses of gas.

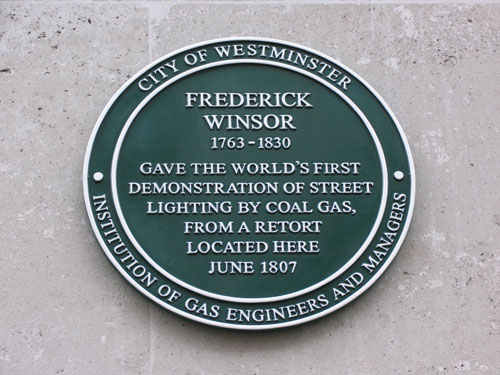

1807 –Winsor leased a pair of houses in Pall Mall where he conducted experiments and public demonstrations, trying to attract investors for his plans. He installed 13 lamp-posts in Pall Mall fed by a pipe buried under the pavement from his house. On January 28, he introduced the first gas street lights in the world. The lights stretched from St James’s to Cockspur Street and when lit, observers noted their light had “much superior brilliancy”. On June 4 of that year, to celebrate the King’s birthday, Winsor placed gas lights along the walls of Carlton Palace Gardens between the Mall and St. James’s Park. The gas was again supplied by the furnaces inside his house on Pall Mall.

Many people did not believe the city could be lit in this way, including the renowned scientist Sir Humphrey Davy. Some thought that the gas came through the pipes already on fire, which of course seemed dangerous! Rowlandson did a cartoon of the lighting in Pall Mall:

In 1809, Parliament did not approve Winsor’s “national company”, but finally Winsor “and his associates” (Samuel Clegg?) did obtain a Royal Charter for their London and Westminster Gas Light and Coke Company to supply gas to those cities and the borough of Southwark for 21 years. On New Year’s Eve, 1813, the Westminster Bridge was lit by gas. Gas began to flow through the London streets that year and soon other companies were seeking permission to lay their own gas pipes. The laying of gas lines –think of all the construction in those busy streets!! Is it unromantic to have our characters inconvenienced by the mess?

By 1823, “40,000 lamps covered 215 miles of London’s streets.” And by 1826, “almost every city and large town in Britain, as well as many in other countries, had a gas works, primarily for lighting the streets. In these towns, public buildings, shops and larger houses generally had gas lighting but it wasn’t until the last quarter of the 19th century that most working people could afford to light their homes with gas.” (From the National Gas Museum website: http://nationalgasmuseum.org.uk/gas-lighting/)

Apparently the “gas works” were discussed in an episode of Downton Abbey (since gas was still primarily in use in the 1920’s) –I don’t watch that series so someone else might comment!

It’s interesting to note that in 1808, Murdoch read a paper before the Royal Society, staking his claim as the first to harness gas for a practical purpose. He said, “I believe I may claim both the first idea of applying and the first application of this gas to economical purposes.” He received the Society’s Gold Medal recognizing his work.

In June 2007, the Westminster City Council installed a Green Plaque at 100 Pall Mall, London, to mark the the bicentenary of the “World’s First Demonstration of Street Lighting by Coal Gas”, marking Winsor’s achievement.

June 2007, the Westminster City Council installed a Green Plaque at 100 Pall Mall, London, to mark the the bicentenary of the “World’s First Demonstration of Street Lighting by Coal Gas”, marking Winsor’s achievement.

As for gas lamps still in use, this website: (http://www.urban75.org/london/london-gas-lamps-and-gaslighting.html) has a collection of photos of gas lamps still in use in London and their locations – a surprising number of them! And also a photo of a modern day lamplighter. Who knew?

And another “who knew?” –the connection between street lighting and crime is once again an issue in Britain, where a December 2014 report states that all over England communities are switching off or dimming their street lights to save money. Heading back to the 18th century, anyone? (http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/safety-risk-as-councils-dim-or-switch-off-a-quarter-of-street-lights-9939124.html)

Let’s talk about it! Please comment on anything you read here. 🙂

Thanks for this very detailed post, Gail. I confess I never thought much about it, but then I often write stories set in the country, not London where it started.

So cool about the extant gas lights! Love the pictures.

Thanks, Elena! I loved those too. It was a neat surprise to find there are still some around! Although to be accurate, they are no doubt fitted with mantles and timers, improvements that came along late in the 19th century. But still. 🙂

Fabulous work Gail! I find it fascinating that gas lights are tallied much about in our readings too. And I remember another author talking about gas lamps during the Regency time on a post too a year or so ago. But the closes book I can think of to referring to gas lighting is Jillian Stone and her Gentlemen of Scotland Yard series.

ki pha, I haven’t read the Jillian Stone books –I’ll have to check those out! They sound interesting.

Thanks for the compliment. It’s probably not the smartest way to spend my time, researching a topic that’s NOT part of the current wip(s), but once I got started, I didn’t want to stop. I think I did run across a post on one of the Jane Austen websites that was from a year or two ago. I wonder if that was the one you recall? There’s a lot of good info out there.

Fascinating research, Gail !! Hmm, the effect gas lights might have had on the criminal element during the Regency makes for some great scene ideas!

Oh, yay, Louisa, if my research sparked some ideas for you! Studies have shown a definite correlation between improved lighting and reduced crime, despite some arguments against this idea. I imagine it was NOT a welcome change for some of the criminal elements! OTOH, during the construction phase, the added congestion and perhaps detours required might have also offered criminals some extra opportunities.

Gail, this is fascinating and must have taken you some considerable time and effort. Thank you for posting it. I remember as a child in the fifties going on holiday to a caravan in fife. My dad had sort of borrowed it sort of rented it – you know the kind of thing. anyway, it had gas mantles to light it. They were very difficult to manage and a lot of time was spent finding hardware stores to replace the ones fingers had gone through. Anne Stenhouse

Anne, that sounds like a fascinating adventure!! The mantles were an improvement (you might not agree? LOL) invented later in the 19th century. In the Regency they just directly lit the gas itself. I learned that they also later added timers and other improvements, so the remaining gas lights in London now are much improved from their Regency versions, but the look is still the same!

Very interesting, Gail. Gas lighting plays a part in my next book, which is set in 1817. The theatres were mostly lit by gas then, despite complaints about the smell, and night time shopping became popular because the goods looked so special under the bright gas lights. But again, the smell meant that the shops had to keep their doors open or the customers left.

There were a number of gasometers around London, piping gas to streets and buildings. All really interesting stuff!

Jo, I love that you’ll be using that!! I look forward eagerly to reading your new one –I always love your books. Title? Release date? My last one (The Rake’s Mistake) was set in 1817. Now I’m planning a new series that takes off from there, so have been researching 1818 and on –“late” Regency! There are so many interesting details about life in that time period we can use, if we are careful not to overload the stories, of course….