When I wrote The Magnificent Marquess back in my Signet Regencies days, I did a lot of research not only about India during the Regency period and the British people who went there, but especially about people’s attitudes towards India back in England, since that is the setting for the story. Not surprisingly, considering human nature, those attitudes ranged all over the place, and I tried to reflect that in the book. The East India Museum was established in London in the headquarters of the East India Company on Leadenhall Street between 1801-04, although in its early days it was known as the “Oriental Repository”, a much more apt name, as you will see if you read on. While it gets a passing mention in TMM, I did a deep dive into its history last spring as one part of my contributions to the Beau Monde’s month-long class, “A Tour of Regency London.” I thought you might enjoy this somewhat shortened version.

The East India Company fronted on Leadenhall Street in London starting early in its long history. Founded in 1600, the company sought a dedicated building of its own by 1648, leasing an Elizabethan mansion known as Craven House. That building was eventually purchased and continued to serve (along with the surrounding area) through several expansions and reincarnations. It was completely rebuilt between 1726-1729. By the 1790’s, however, even that version was no longer sufficient for the huge entity that was the East India Company. The grandest structure of all was created between 1796-1800. The buildings on either side were purchased and torn down to allow side expansions, and a new front elevation designed by the architect Henry Holland. This was the massive edifice that Regency tourists flocked to see, and which eventually housed (as an adjunct to its library) the collections of the “repository,” or museum.

A period guidebook, The Picture of London (for 1802), tells us: “It has been enlarged and adorned with an entire new front of stone, of great extent and much beauty, having a general air of simplicity and grandeur.” It notes that the interior is also “well worth visiting” and compares the domed sales room to the rotunda of the Bank of England.

Plans for the new expansion of the building included the creation of a library, reading rooms, and a museum, “to house the natural history specimens, books, samples of manufactures, manuscripts and other miscellaneous items collected by the Company and its officers in India.” [Desmond, Ray. The India Museum, 1801-1879. London: H.M.S.O., 1982].

The phrase “miscellaneous items” gives an apt idea of the company’s attitude towards the artifacts that were ultimately collected in the “repository.” Most of the populace still knew surprisingly little about the history and culture of the subcontinent, considering how deeply connected they (or at least those wealthy enough) were, through the imported products they used every day, the events in the news and the sheer numbers of British people who had been making careers there, either military or commerce-related, for over two centuries. The museum would offer glimpses to any who were interested enough to look.

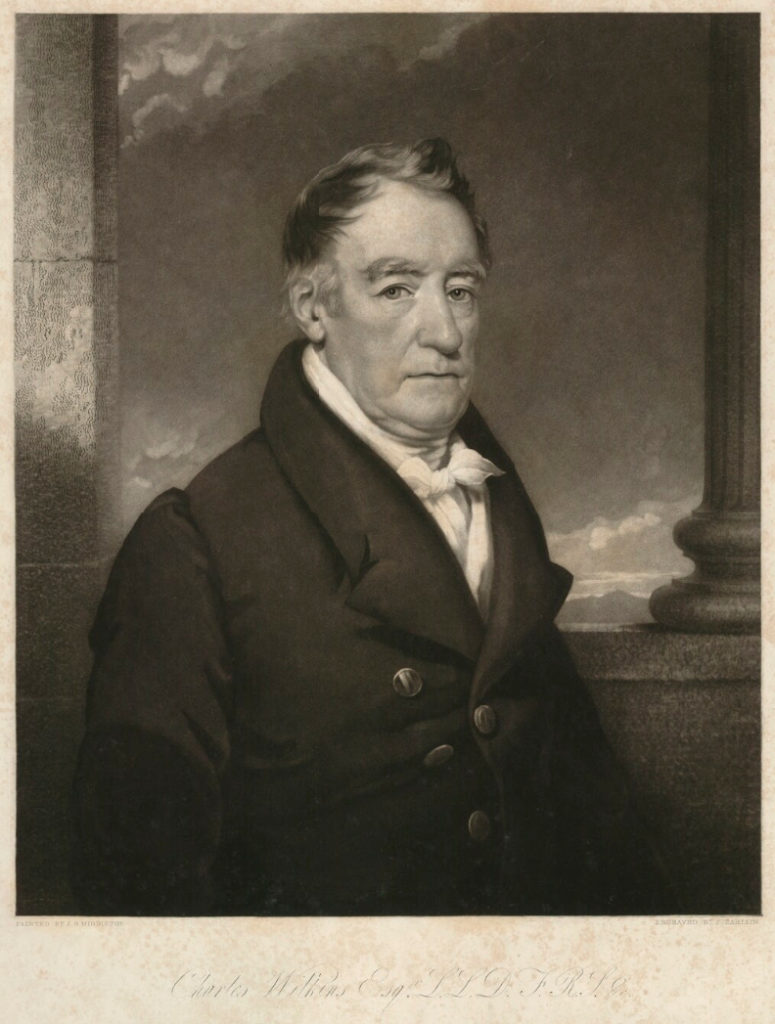

No mention is made of the library or museum in the early guidebooks. Most sources agree that they did not open until 1801 (one says 1804). Charles Wilkins (knighted in 1833), who had spent 16 years in India, was appointed as the first director of the library, and as such was also the de facto first curator of the museum, although it was not a separate entity at that time. Wilkins’s great interest was in languages. He mastered both Bengali and Persian, and designed typefaces to enable the print publication of books in both languages. He also studied Sanskrit and translated and published many great works of Indian literature.

Given his scholarly interests and activity, it may not be surprising that Wilkins was chosen to direct the new Oriental Repository at India House, or that the printer and translator was not well-suited for a librarian’s job. No doubt the company’s extremely casual attitude toward the collections also did not encourage Wilkins (or those who followed after him) to make the library’s maintenance or organization a priority among his other projects. It was, indeed, merely a “repository.”

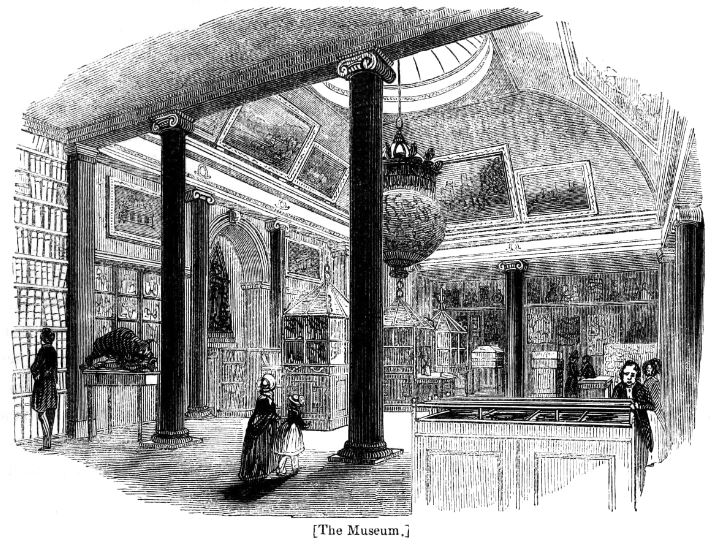

Sadly, records and inventory for the Regency years of the library and museum do not exist. No catalogue of holdings was maintained. Records of the pieces that ended up at the Victoria and Albert Museum only go back to 1843. So we don’t know what the Regency visitor who gained access was able to see. Or even how easy or hard that access was. Or even exactly where it was. Wikipedia says that when the new expanded building was completed, “The Company’s museum was housed in one extension, the library in the other.” No source is given, but certainly the museum had very little in it to start, and at later dates it, or parts of it, were definitely housed in the library’s reading room. The Picture of London from 1822 may not be the first reference but it is the first I found that included the East India Museum in its list of exhibitions along with a description. It says:

This may be the best inventory of these treasures on record, despite errors such as identifying Tipu’s symbolic tiger as a lion. Clearly at the time, the public was invited to visit on scheduled days. At other times, an application had to be submitted and approved. It is interesting to note that no mention is made of the museum’s most famous artifact, the automaton/musical instrument of Tipu Sultan’s Tiger, which after several years in storage made its public debut at East India House in July of 1808. “Tippoo’s Tiger” is a nearly life-sized wooden sculpture of a royal tiger (Tipu’s personal emblem) attacking a European. It is an automaton, a playable miniature organ, and not least, a political statement by an Indian ruler whose hatred for the British is very clear. (I have talked about this automaton in previous posts, first here .)

The brutal storming of Tipu’s fortress at Seringapatam (Srirangapatna) in 1799 captured the imagination and curiosity of the British public for many years after the event. A panorama depicting it in 1800 was a great success. The tiger automaton first appeared in England as the frontispiece for the book A Review of the Origin, Progress and Result, of the Late Decisive War in Mysore with Notes by James Salmond, published in London in 1800, before the tiger had even arrived. The battle was featured as a vast spectacular at Astley’s Amphitheatre, and cut down to size for a juvenile drama. As late as 1868 it set the scene for Wilkie Collins’s novel The Moonstone. G. A. Henty wrote a fictional account, The Tiger of Mysore, and then there’s Bernard Cornwell’s offering in the Sharpe series, Sharpe’s Tiger.

The problem with artifacts from the fortress of Tipu Sultan (aka Tippoo Saib, Tippoo Sultan, and King of Mysore) was that British soldiers had gone on a frenzy of looting once their victory was secure, one that Wellington finally managed to stop, but not before a great number of valuable items were seized by individuals. Many of these eventually made their way to the museum, but only decades later. They were not on display in the museum’s early years. It is supposed that what saved the tiger automaton was that he was made of wood, and therefore had no intrinsic value to the looting soldiers.

Both visual and written documentation prove that Tipu’s Tiger resided in the library reading room at East India House, where poet John Keats saw it in 1819, and the French poet Auguste Barbier saw it in 1837. Both commemorated it in their poetical works. We also have a view of the reading room in 1841 clearly labeled as “the museum” and it shows a number of display cases besides the notable presence of the tiger (at far left).

That display location continued in the following decades, too, for the complaints of those trying to use the reading room while visitors cranked the tiger into motion are also documented. The musical and noise-making aspects of Tippoo’s Tiger suffered over the years from public exposure and use, and gradually fell into disrepair. Eventually the crankhandle that powered the sound effects of the tiger disappeared. The Athenaeum magazine reported in 1869:

“These shrieks and growls were the constant plague of the student busy at work in the Library of the old India House, when the Leadenhall Street public, unremittingly, it appears, were bent on keeping up the performances of this barbarous machine. Luckily, a kind fate has deprived him of his handle, and stopped up, we are happy to think, some of his internal organs… and we do sincerely hope he will remain so, to be seen and admired, if necessary, but to be heard no more”.

I found one item definitely documented as a Regency era donation (based on the donor’s date of death) among the Victoria & Albert Museum’s collection. It is a “small standing figure” of Vishnu, “given to the India Museum, London, by Colonel Colin Mackenzie (1754- 1821), who may have acquired it some time around 1800-10.” (shown at left, courtesy V&A Museum, 2017KA5265)

Another famous item that was definitely on display in our period (donation date uncertain) was the Nebuchadnezzar II Stone Inscription Tablet unearthed before 1803 in the ruins of Babylon by Sir Harford Jones Brydges, then British Resident in Baghdad. Later, Brydges presented it to the museum of East India House. It has since been known as the East India House Inscription. (Probably originally buried in the foundations of one of King Nebuchadnezzar’s numerous constructions in Babylon between 604 and 562 BC.)

Beyond these two items, we can only guess at what else was displayed. But I found several items from Seringapatam that might have been typical, via a fascinating website on the history of textiles offered by the Textile Research Center. TRC is a charitable educational foundation based in the Netherlands.

Some are examples from a 2015 auction by Bonhams in London, which sold off a collection of armoury “taken from the fortress of Seringapatam (Srirangapatna), the last refuge of Tipu Sultan of Mysore…in 1799 A.D.” These items may well have remained in a private collection for the entire 216 years prior to that year. I have no idea who purchased them or where they have gone since, but similar items may have been in the India House Museum during the Regency. The site description says: “Apart from a quiver, armguards and a belt, the collection included sabres, gem-set trophy swords, exquisite quilted helmets, blunderbusses, fowling pieces, sporting guns, pistols, and a three-pounder bronze cannon.”

The quiver, armguards and belt are decorated with gold thread embroidery and spangles, on a red ground.

Other pieces shown on their site include a “Saddle cloth of crimson Genoa velvet thickly embroidered with gold thread in conventional foliage pattern, &c. (Indian, formerly the property of Tippoo Sahib)”:

a Beetlewing embroidery example that “used to be part of the collection of the India Museum and was transferred to the holdings of the South Kensington Museum in 1879/1880”

https://trc-leiden.nl/trc-needles/techniques/applied/beetlewing-embroidery

and an example of the “exquisite quilted helmets” mentioned in the auction along with a detailed description: “The quilted helmet is provided with a gold kaftgari (a form of Damascene work), steel nasal bar, inscribed with the names of Allah, Mohammed, Fatima, Ali, Hassan and Husain (clearly a reference to a Shi’ite origin). The decoration of the helmet includes gold thread embroidery on a red ground. There is also an interlocking shell design worked in metal thread on a blue ground. In the centre of each shell there is a single spangle.”

(If links do not work, please try copying and pasting?)

The attitude of the company towards these kinds of artifacts was a huge part of the problem. To them, and to most of the public, the items did not represent the rich history, culture, artistry and craftsmanship that we see in them today. They were “curiosities”— interesting, to be sure, but not considered important.

In the 1830’s, the museum came under public attack for its negligence in managing the library (and museum) collections. Apparently, as far as I have pieced together, a scholar named Peter Gordon took it upon himself to begin to asses the collections in the library. Unfortunately for us, he was mainly concerned with the manuscripts, books and records. The only specific museum artifacts I found mentioned were coins, medals, 35 “Hindu idols” sent in 1822, and a “gold salver.” But Gordon was aware of the great collections that had been bequeathed or forwarded to the museum, and listed many. He found many, many discrepancies, missing volumes in sets and missing material that had supposedly been sent years earlier.

When he communicated these faults to the Company Directors, they, rather than showing concern about the problems, took issue with what he was doing, and banned him from the library. Incensed, Gordon published his findings along with the letter dismissing him. I found these referenced as a book, The Oriental Repository at the India House (London 1835). The book is rare, but I discovered it is apparently a bound version of a scathing article Gordon initially published in Alexander’s East India and Colonial Magazine the same year. The deficiencies he outlines, in between cataloguing as much as he could, more than explain why it is so difficult to know what the museum contained.

At the end of the 18th and beginning of the 19th centuries, three organizations were competing to collect these types of items: the London Missionary Society (LMS), the Oriental Repository in East India House, London, and The Indian Museum, Calcutta. The apparent carelessness of the East India Company directors towards the holdings of their library and museum, once in their possession, portrays the problem of setting a commercial enterprise as a guardian over distinctly non-commercial assets.

Despite this, the collection continued to grow, along with the public’s interest in India. This reached a peak in 1851 with the Great Exposition in the Crystal Palace, where a vast amount of Indian goods were shown and then given to the museum. It became Britain’s largest collection of Indian objects. At least the new artifacts were covered by the 1400-page exposition catalogue, which included a 130-page overview of the displays in the Crystal Palace’s Indian Courts. But then, the Great Rebellion of 1857 happened, and everything changed. The East India Company was disbanded in 1858 and its function taken over by the British government. The India Office was established, and the museum collection was moved to Fife House in Whitehall in 1861.

The huge East India House on Leadenhall Street was demolished in 1863 along with everything it represented, just 63 years after its massive remodeling. Later the holdings were put in storage, and in 1875 they were moved temporarily to the South Kensington Museum. In 1879 the museum collection was formally dissolved. Some of the items went to the British Museum, some to Kew Gardens (according to Wikipedia) and what remained in the South Kensington Museum (later named the Victoria and Albert Museum) reopened in 1880 and was known as the India Museum until 1945.

I found this a sad but also fascinating tale. Did you? Have you read any Regencies where the characters visited the Oriental Repository or East India Museum? Would you have liked to visit it?

Wow! That was fascinating! It’s a shame the building was destroyed and the collection broken up.

Oh, Kris, I couldn’t agree more! But a classic example of how politics and ignorance hamper our study of history and understanding other cultures. As for the destruction of the giant building after 63 years –there’s something that feels really modern about that waste, IMHO!!

Hi,

What wonderful research. Thank you.