Is summer heat making you yearn for the cold temps of winter? Or are you one of those folks who finds the long stretch of summer without a major holiday too unbearably boring? These are two of the reasons people give for celebrating “Christmas in July” –at least, if you’re in the northern hemisphere and/or once the 4th of July is over if you’re American! Years ago I knew a family who held a Christmas-in-July party without fail every year. They would break out all the lights and decorations, do a random gift exchange, the whole bit. It was fun!

Of course, there is also the commercial push, an excuse to hold sales when there’s no other real reason. From the Hallmark Channel to Best Buy ads, it’s hard to escape!

But I’ve always found the concept a bit curious. (Learn more below.) So why am I talking about it now?

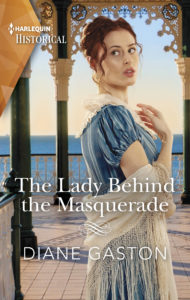

Do you like to read Christmas stories outside of the holiday season? I enlisted my #2-in-series book, Lord of Misrule, in two separate “Christmas in July” book promotions running this month (kind of accidentally, but it seemed like a good idea at the time)!

The first promo is just for historical Christmas stories, which may suit your interest if you follow this blog. Find it here: https://books.bookfunnel.com/christmasinjulyhistrom/otm7wj9bjs. I would appreciate any and all clicks because it shows I am sharing this! You might discover a new-to-you author. They aren’t all Regencies, so if you specialize you might need to sift through them a bit, depending on your taste. Be warned, they are all different heat levels, too. There are 75 books in all, which goes to show how popular this sub-sub-genre is!!

The second promo, at N.N. Light’s Bookheaven.com site, includes a chance to enter a drawing for a $75 Amazon US or Canada gift card (you must have a US or Canadian Amazon account), in addition to highlighting a large bunch of Christmas set stories. These are a mix of all genres, however, so if you’re only looking for historical settings, you’ll need to sift through more. I saw a number of familiar names in there, so it’s worth looking.

If you haven’t read Lord of Misrule, the story is being featured today (July 12) at the promotion webpage: https://www.nnlightsbookheaven.com/post/lord-of-misrule-cijf . Find out what I love best about the holiday season, and why I think this book captures the spirit of Christmas in its pages!

Where did “Christmas in July” first come from? I looked it up because I can never resist a good rabbit hole. It’s certainly not a Regency thing –Christmas then wasn’t the Big Thing we have made of it in modern times. And the playful concept didn’t seem to fit with the staid Victorians, even though they revived or glorified a lot of the other Christmas traditions we think of as old!

The phrase is first noted in an 1892 French opera named Werther, translated into English in 1894. A group of children rehearsing a Christmas carol in the story are told they’re “rushing the season” when they sing “Christmas in July”, but that was not the beginning of it as an event. That honor goes to a North Carolina girls’ summer camp, Keystone Camp in Brevard. In July of 1933 the director of the camp, Fannie Holt, thought up the idea of a Christmas party with singing carols, gift exchanges and all the trimmings, and it became an annual tradition there.

Then in 1940, the movie “Christmas in July” starring Dick Powell and Ellen Drew came out, popularizing the phrase across the US. During the 40’s, some prominent US churches adopted the concept to spread charity ahead of the season, and the US Post Office and military services adoptted it to promote early mailing to those in service overseas during WWII. And from the US, the idea spread internationally.

Have you ever celebrated Christmas in July? Are you a fan of the idea, or does the commercialization of it in current times turn you off? Does reading a Christmas book in mid-summer help you cool off as you think about a snowy setting or the love and wonder that come with the season? I’m sure you agree with me in wishing we could keep that sense of magic all year round.

I am thrilled to announce that I have a new release coming this month!

I am thrilled to announce that I have a new release coming this month!