Why does the WALTZ (or French “Valse”) fascinate us? I’m sure it’s partly because it was so scandalous during the Regency, and partly because we love the potential for romance when our heroes and heroines share the intimate dance. This is a long post!! Bear with me –I couldn’t choose what to leave out.

The waltz existed as a form of cotillion and of English country dances long before the scandalous single couple version of it was introduced to England during the Regency. It is those types of waltzing that Jane Austen references in her writings. Here are links to two examples of country dance waltzes, which utilize the familiar ¾ time rhythm:

The Northdown Waltz 1806 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Xl5Cf2zTKWc

The Duke of Kent Waltz 1801: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6vmUNDR8GE8

The waltz traces back to German peasant dances as old as the 16th century. Its history is similar to that of other dance types: what shocked the aristocracy and at first seemed beneath them eventually was adopted by them, because, well, why should only the peasants have fun? The turning, close-held waltz took hold in the higher regions of society by the 18th century in Bavaria and Vienna, and spread to France, where post-revolutionary society embraced it.

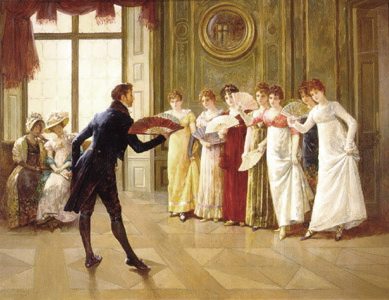

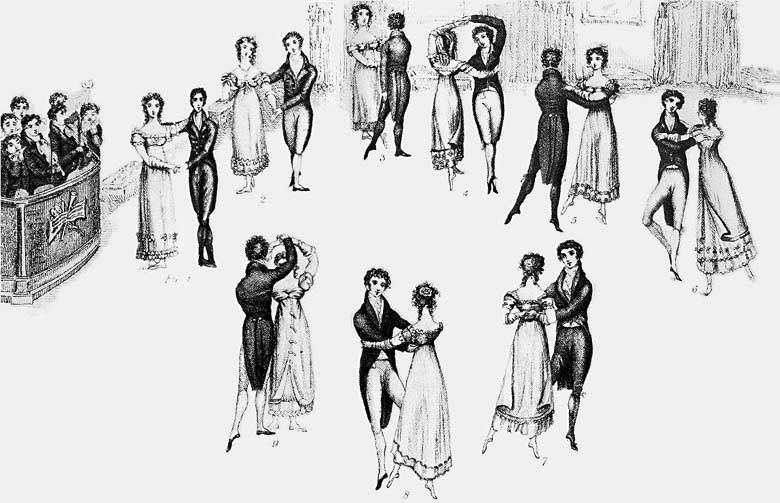

Why was the waltz so scandalous? The illustration at top, while exaggerated, gives you an idea, but this lovely video clip from the BBC explains most of it quite well. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6r0dKkkk2jk Besides the intimacy and close hold was the simple fact that the dancers were turning for much of the time, which could lead to ladies becoming dizzy and quite shockingly out of control of themselves!

In 1804 a German visiting Paris wrote, “This love for the waltz and this adoption of the German dance is quite new and has become one of the vulgar fashions since the war…” [the French Revolution]. The “new” form of waltz trickled into England slowly, scandalizing most of English society when they first saw it. The German ex-pats who made up the soldiers of the King’s German Legion are credited with introducing the waltz to residents of Sussex in 1804, but it was slow to catch hold in England, where moral codes were strict (well, stricter).

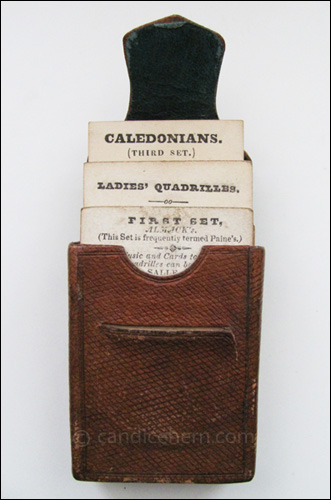

In 1814, neither the waltz nor the quadrille were yet permitted to be danced in Almack’s. Some theorists say attendees at the Congress of Vienna (Sept 1814) first saw the dance there and brought it back to England. But Princess Lieven, wife of the Russian ambassador assigned to England starting in 1812, had been in Berlin prior to that assignment, so it makes sense that she learned the dance while there. She was the first foreign-born patroness of the mighty Almack’s social club and is said to have introduced the waltz there in 1815.

Dance Master Thomas Wilson’s book “A Description of the Correct Method of Waltzing” came out in 1816. His famous illustration of the “nine positions of the waltz” is below (you can see the numbers underneath each one if you look closely). By then, the dance had become prevalent enough to be ridiculed by the cartoonists of the day, and popular with the young who always want the “new” thing.

The royal courts, generally foremost in setting fashions in many areas, consistently lagged in the area of dance. In July of 1816, the waltz was included in a ball given in London by the Prince Regent. A few days later an editorial in The Times complained: “We remarked with pain that the indecent foreign dance called the Waltz was introduced (we believe for the first time) at the English court on Friday last … it is quite sufficient to cast one’s eyes on the voluptuous intertwining of the limbs and close compressure on the bodies in their dance, to see that it is indeed far removed from the modest reserve which has hitherto been considered distinctive of English females….”

The Regency form of waltz was closely related to other dances: the German Landler, and the French Allemande, and the other dances that drew on these forms. At her Capering and Kickery website (kickery.com) dance historian and teach Susan de Guardiola writes: “The early waltz looked quite different than the modern form. Dancers moved on their toes in a different pattern than what is seen in today’s competitive ballroom dancing, and adopted a wide range of “attitudes” of the arms…. Nor were waltzes choreographed, though Wilson suggested dancing different waltzes in sequence [slow followed by lively and back to slow again]. Entire ballrooms of dancers did not perform identical moves.” [Gail’s note: The name sometimes used for Regency waltz is the “pirouette waltz”.]

This video of five dances performed at the Royal Pavillion in Brighton is long, but at about 5:40 the dancers perform “The Allemande a Deux” (1780) which is a French modification of a German Landler. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=17QPpXyCql4

If you compare it to the video of the single couple performing the Regency waltz (see next link), I think you will see some of the similarities, and you will also get a sense of how Regency waltzers did not all do the same figures at the same time. Regency Waltz/Valse 1826: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_7B_Qsdnn5E (Video from the French National Historic Dance Championships –you have to love a country that holds such a thing!!)

If you are interested to know more, I found a fun video that compares the Regency style “pirouette” waltz to the later versions, here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fq0QxdsoUzo

Do you think our modern version of the waltz has lost some of the “spice” of this earlier style? Or are you glad that our version is a lot easier to dance?