For me, reading stories in the Tatler (which I think of as Britain’s version of People magazine), often feels like what I can imagine a Regency heroine’s mother doing: catching up on the recent doings of society’s leaders and celebrities of interest. But an article in the November 7th issue particularly caught my eye, because anything that relates to our favorite time period, the Regency era, always does. Who here wouldn’t be curious about an article titled, “Tiara of the Month: the 200-year-old Danish headpiece crafted for Napoleon’s coronation”? (deep rabbit hole warning!)

The tiara in question was crafted for the wife of one of Napoleon’s marshals. The article describes it as “dazzling pavé set diamond leaves which support clusters of ravishing rubies styled as berries,” originally part of a parure. (You can see a photo of its modern incarnation in the article, linked at the end of this post.) The article’s author, Emma Samuel, points to Napoleon’s “understanding of impressive decorative symbolism” and writes that Napoleon “apportioned funds to his trusted marshals and their wives so they could attend his crowning in splendid attire.”

The particular marshal-husband in this case was Jean-Baptiste Bernadotte (1763-1844).

The son of petit-bourgeois parents, he was a 26-year-old sergeant in the French army at the start of the revolution in 1789. Like another ambitious young man (Napoleon Bonaparte), Bernadotte distinguished himself and rose quickly during the revolutionary years, becoming a brigadier-general by 1794. He advanced his political connections greatly when in 1798 he married Désirée Clary, a young woman who had previously been affianced to Napoleon (until he met Josephine de Beauharnais) and whose sister Julie had married Napoleon’s brother Joseph. (Two novels have been written about Clary’s life and two films, one French and one American, have been made.)

The tiara of the Tatler article, known as the “Ruby Wreath Tiara,” was created for her in 1804. Is it what she is wearing in this portrait?

Hard to say, since the piece apparently was restyled numerous times.

Désirée was among the young women attending Josephine at the coronation in 1804, so perhaps David’s famous depiction of the event shows her wearing it as one of these (pictured at top).

But how did this French tiara come to be known as a Danish headpiece?

Ah, that’s where the crossovers and connections that thread through all of Europe’s royal families come into play.

Before the tiara became Danish, it first became Swedish!

Bernadotte reaped rewards from his military accomplishments and his connection to Napoleon. He became Prince of Pontecorvo in 1806, and was serving as the governor of northern Germany in 1808 when he first impressed Swedish troops stationed there. Among them was a young lieutenant, Baron Carl Otto Mörner who also happened to be a courtier to the Swedish crown.

When Bernadotte was about to become the governor of Rome in 1810, he was invited to become the Crown Prince of Sweden instead. Mörner had advocated for his selection when the existing crown prince died unexpectedly, leaving the ailing Swedish king Charles XIII without an heir. In fact, Mörner had overstepped his own authority and extended the offer to Bernadotte without waiting for the government to first approve or act, for which insubordination he was imprisoned!

Was his move merely youthful enthusiasm, or a calculated gamble? Even deeper research might never answer this question. Fortunately for the baron, either way his action worked. The Swedish government subsequently did approve and act on his recommendation.

No doubt Napoleon thought having his own man in Sweden would prove useful. Bernadotte sought and received Napoleon’s permission to accept. He was formally adopted by the Swedish king under the name Charles John and was elected Crown Prince of Sweden all in the same year.

Astute as well as ambitious, he worked at gaining influence and popularity while the king still lived. He saw that with Russia in control of Finland, Sweden needed to follow a pro-Russian foreign policy. This caused new friction with Napoleon and after more Napoleonic actions against Sweden’s best interests in 1812, led to a formal split between the countries.

Sweden joined the Allies in 1813. Bernadotte (Charles John) led the Swedish military against Napoleon in the last years of the wars, and after Napoleon’s defeat Sweden was rewarded with the annexation of Norway. King Charles XIII died in 1818 and Charles John became the new king, reigning until he died in 1844. He founded the royal House of Bernadotte, from which the current royals in 2023 are still descended.

But what of Désirée and the ruby tiara?

Désirée Clary was the daughter of a wealthy silk merchant, barely 18 years old when she became affianced to Napoleon Bonaparte. Her sister Julie, with whom she lived and was very close, married Joseph Bonaparte and ultimately became the Queen of Naples and Spain. But Eugénie Désirée was a homebody at heart, not interested in politics or position, devoted to her family and happiest when living in Paris. She was 21 when she married Bernadotte in 1798, and perhaps unprepared for becoming a political pawn between her husband and the rapidly advancing Napoleon.

Bernadotte knew the importance of social connections and had his young wife taught dance and etiquette suitable for a position in high society. Through her sister, Désirée maintained a good relationship with the Bonaparte family. She escaped having to be a lady-in-waiting to Josephine and lived a comfortable, enjoyable life in France, mostly absent from her husband, although she had given him a son, Oscar, in 1799. It was a shock when she learned she would be expected to reside in Sweden when he became the Crown Prince there.

She delayed and arrived there in winter with her 11-year-old son and French courtiers, hating the snow so much she cried. She could not adjust to the strict etiquette required in the royal court and did not attempt to learn the Swedish language. The Swedish royals found her constant complaints and pining for France wearing despite trying to like her. Her French entourage did nothing to endear her to anyone there. She returned to France in the summer of 1811, but was not allowed to take Oscar with her. As his father’s heir, he was to become a Lutheran and live in Sweden to be trained in the ways of royalty.

She lived once again in her beloved Paris, incognito under the pseudonym Countess of Gotland for political reasons. She did not meet her son again until 1822, when he came to central Europe to choose a bride. Ironically, Oscar chose Joséphine of Leuchtenberg, a granddaughter of Napoleon and Désirée’s old rival Empress Josephine Bonaparte. Désirée returned to Sweden to celebrate her son’s wedding in 1823, accompanying her daughter-in-law. She never returned to France despite her intentions to do so, and the ruby wreath tiara passed to Joséphine.

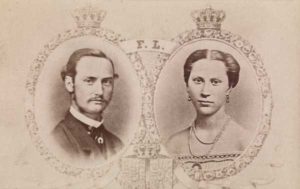

Oscar and Joséphine had a true marriage, despite infidelities on his part, and they had five children. As their only daughter never married, two of their sons died without issue, and one son had only sons, the ruby wreath tiara eventually went to Princess Louisa, Joséphine and Oscar’s only granddaughter through their eldest son Charles (Carl Ludvig Eugen, King Charles XV of Sweden). And there at last we come to the connection to Danish royalty, for Louisa married Prince Frederick of Denmark in 1869 when she was 18 and he was 25.

He became King of Denmark in 1906, only 6 years before he died. But between 1870 and 1890, he and Louisa produced eight children who were connected to royal houses around Europe, including sons who became the kings of Denmark and Norway, and royal families of Belgium and Luxembourg descended from their daughter Princess Ingeborg of Denmark (born 1878), who married Prince Carl of Sweden, her mother’s cousin, in 1897.

Did you get all that? I admit this blog article is probably one for the extreme history nerds, or those who enjoy following the tangled threads of royal relationships by marriage. But the deeper I went down this rabbit hole, the more interesting characters showed up in the story! The ruby wreath tiara remains in Denmark, where, according to the Tatler, it is “one of Crown Princess Mary of Denmark’s favourite diadems.”

Do you like sparkly things? To see a photo of it in its current form, check out the article here: https://www.tatler.com/article/ruby-wreath-tiara-crown-princess-mary-napoleon-tiara-of-the-month

All pictures used in this post were sourced from Wikimedia Commons and are copyright free.

Happy holidays, to everyone who celebrates them!