The first Wednesday of October is the traditional date for the Nottingham Goose Fair, which today is a huge pleasure fair. But as its name suggests, in former times, one of the main goods being sold at that fair were indeed geese.

The time around Michaelmas (also known as the Feast of the Archangels or the Feast of St. Michael and All Angels) on 29 September was traditionally a time for goose-eating in England — according to legend, because Queen Elizabeth received news of the defeat of the Spanish Armada on Michaelmas Day, just when she had sat down for a meal of roast goose. She thus declared (again, according to legend) roast goose should forevermore be eaten on Michaelmas day in celebration of England’s might.

The truth is a bit more mundane: by the Tudor age, goose eating had already become connected to Michaelmas – probably because it is one of the old quarter days, marks the end of the harvest season and the beginning of the new farming year. Incidentally, spring geese are big enough to be slaughtered by the end of September and thus, a goose became a customary gift of tenants to give to their landlord when they were paying the rent on Michaelmas Day.

Not surprisingly then, at a lot of fairs held around the country around Michaelmas the wares that were being sold included geese. Most of these goose fairs have been long forgotten, but Nottingham Goose Fair is one of the few exceptions.

The fair has a very long tradition: in some form or another, it might have existed even before the Norman Conquest, and it had received its name, “Goose Fair,” by 1541. Originally, the main event of the far was indeed the selling of geese. An article from the September 1871 issue of Golden Hours: An Illustrated Monthly Magazine for Family and General Reading mentions that a “street on the Lincolnshire side of Nottingham is said to be called Goose-gate from the numbers which were driven through it for the annual goose fair, when from 15,000 to 20,000 of those birds were brought from the Lincolnshire fens, each flock attended by a goose-herd with a crook, wherewith to catch and lead out any goose which a possible customer might desire to examine more closely.”

By the 19th century, it was considered lucky to eat goose on Michaelmas Day: according to a proverb, you’d never lack any money if you ate goose on Michaelmas Day. And in 1813, in a letter to her sister, Jane Austen writes, “I dined upon Goose yesterday — which I hope will secure a good Sale of my 2d Edition” (i.e., the 2nd edition of Sense and Sensibility).

Today, only the name of the Nottingham Goose Fair and the sculpture of a giant goose in the town serve as reminders of the old purpose of the fair, which by now has become a giant pleasure fair.

The Nottingham Hidden History Team has a picture of said sculpture as well as a few pictures of the fair in earlier centuries.

~~~

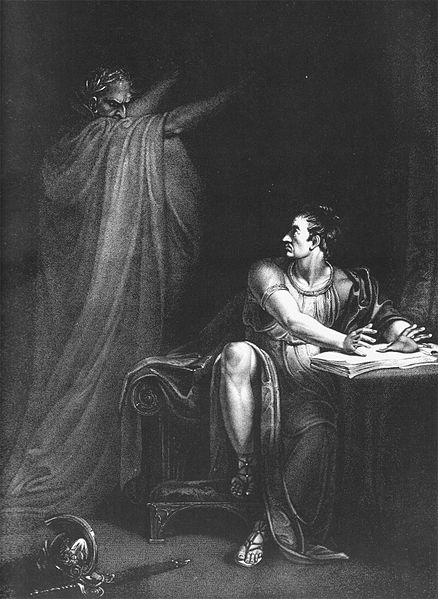

In other news: A couple of days ago, I sent my latest WIP to my editor. “The Centurion’s Choice” is a spin-off novella from my Roman series and will be ready for release at some point in November. (And poor Lucius doesn’t have any nipples in this picture. *sigh* Sandra Schwab, forever forgetting to give her male digital models nipples.) (He totally will have nipples on the finished cover!!)