Did you know the first “photograph” was made during the late “extended” Regency period? Its inventor, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, is the second of my “real Regency heroes” to hail from France rather than England. My justification is that scientists who studied and experimented with technological advances at this time worked and shared on both sides of the channel.

“photograph” was made during the late “extended” Regency period? Its inventor, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, is the second of my “real Regency heroes” to hail from France rather than England. My justification is that scientists who studied and experimented with technological advances at this time worked and shared on both sides of the channel.

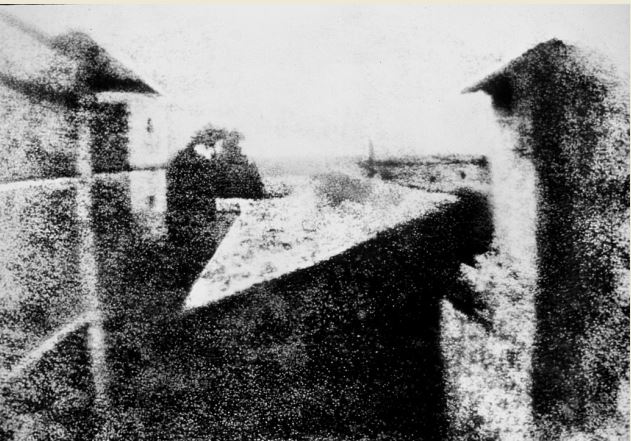

Niépce developed other innovations as well, but according to correspondence with his brother, he captured the first permanent live camera image in 1824. This first effort was lost in further experimentation. But in 1826, Niépce created the same image again—a view out of the window from his studio—and this image still survives today, the world’s first (if rather indistinct) photograph.

Buckle in for a story that shows how luck and timing and good PR, or the lack of them, make a huge difference in scientific success.

Born in 1765, Niépce was the second son of a wealthy lawyer. He and his older brother Claude excelled in studying science and after graduating Niépce became a professor at the Catholic Oratory college where he studied in Angers. The order’s colleges were shut down in 1792 by the Legislative Assembly of France’s New Republic, and some teachers became active supporters of the revolution. Niépce briefly joined the army under Napoleon and served as a staff officer in Italy and Sardinia until ill-health forced him to resign and accept a position as the Administrator of the district of Nice. He also married at this time.

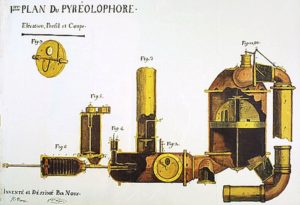

In 1795 at the age of 30, Niépce left that position in order to pursue his scientific interests, partnered with his brother Claude. They researched ideas for an internal combustion engine, living in Nice until they returned to their family estate in Chalon in 1801. Reunited with other family members, they lived there as gentlemen farmers while exploring a variety of scientific interests. In 1806 they presented a paper to the Institute National de Science, the French National Commission of the Academy of Science, which explained the workings of their engine, which they called a Pyréolophore.

In 1795 at the age of 30, Niépce left that position in order to pursue his scientific interests, partnered with his brother Claude. They researched ideas for an internal combustion engine, living in Nice until they returned to their family estate in Chalon in 1801. Reunited with other family members, they lived there as gentlemen farmers while exploring a variety of scientific interests. In 1806 they presented a paper to the Institute National de Science, the French National Commission of the Academy of Science, which explained the workings of their engine, which they called a Pyréolophore.

In 1807 they built a working version of their engine and demonstrated its success by powering a boat up the River Saone. They received a ten-year patent from Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte.

Unfortunately, in the same year Swiss engineer François Isaac de Rivaz also built an internal combustion engine. The de Rivaz engine was hydrogen-powered, whereas the Niépce engine ran on various experimental fuels such as mixtures of Lycopodium powder (the spores of clubmoss) and coal dust, or resin, all of which proved expensive.

France under Napoleon was at war for nearly all of the years of the Niépce patent. During those years, the brothers also developed a hydraulic pumping machine (but too late to obtain the government contract they aimed for) and the first fuel injection engine. But they were not able to attract sufficient investments or subsidies for their Pyreolophore, so their engine patent expired in 1817.

Unwilling to release the project, brother Claude traveled to England and settled at Kew. He obtained a patent consent from the British Crown in December of 1817, but for the next ten years he pursued many ill-advised and unsound schemes to promote the engine. He was said to have “developed delirium” (probably some form of dementia) and squandered most of the family fortune.

Meanwhile, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce had already turned to new interests, among them building a velocipede (early bicycle) that he rode around Chalon. Starting around 1816, another interest was combining the process of lithography, invented in 1798, with the idea of capturing photographic images using a camera obscura. Today the process he invented is known as photo-lithography.

The problem with camera obscura images, long used as an aid to artists, was that no one had found a way to capture them in a permanent form other than drawing them. Dissatisfied with the results obtained with silver oxide-coated paper, Niépce turned to bitumen, used on the copper plates for making engravings. He developed a process he called heliography, which allowed him to copy existing engravings by laying them in the sun on a lithographic stone or a sheet of metal or glass that had been thinly coated with bitumen dissolved in lavender oil, leaving a reproducible impression on the plate.

Attempting to capture a camera image on such a plate was not a huge leap. Niépce set up a camera obscura in the window of his studio and in his first try, projected the image onto bitumen-coated stone. His second version was projected onto bitumen-coated pewter, and that is the image that survives to this day. At one time the exposure time was thought to have been eight hours but further recent research has shown in fact the exposure took several days, which is why the sunlight in the image does not come from only one direction!

Niépce traveled to England to see his seriously-ill brother late in 1826. While he was at Kew, he met botanical illustrator Francis Bauer and showed him the heliography prints and the photograph. Bauer encouraged him to share his discoveries with the Royal Society. However, the paper Niépce presented to the Society was rejected because he was too reluctant to divulge the details of his work.

Niépce left his samples and his paper with Bauer and returned to France, where he partnered in 1829 with Louis Daugerre, who was also investigating ways to capture camera images. But Niépce died suddenly of a stroke in 1833, so impoverished that the French government paid for his burial. When Daugerre presented his own process, the “daugerreotype” to the world in 1839, he claimed the recognition as the inventor of photography, over the protests of Niépce’s son. Bauer managed to have Niépce’s work exhibited at the Royal Society, but nonetheless Niépce was mostly forgotten until the modern age.

In 1952, a pair of photography historians, Helmut and Alison Gernsheim, managed to track down what had become of Niépce’s photograph and acquired it. Their collection was purchased in 1963 by the University of Texas. Niépce’s reputation has finally been restored, and his original first photograph can be seen today on display at the university’s Harry Ransom Center in Austin, Texas. Did you have any idea that photography had such an early beginning?

(all images used with this post are public domain)