“Dropping the ball” in the modern sports-inspired idiom means failing to carry through on some task or responsibility, which seems appropriate given my failure to post this article sooner. I fully intended to post it at the beginning of the month, but life got in the way (my husband got a pacemaker implant and needless to say my attention was mostly on him!). But if your January has sped by as fast as mine, it should not seem long since New Year’s Day, LOL!

I bring up ball-dropping because on New Year’s Eve it has become a “time-honored” custom (since 1907) to drop a giant electronic time-ball from a tower in Times Square, NYC, to welcome in the new year. But did you know that the “ball drop” tradition ties back to maritime England in 1818? Yes, solidly within the Regency period.

Wikipedia says the ancient Greeks used a ball drop to help track time, but the first “modern” time ball was created and installed in Portsmouth, England. Here’s a quote from the article:

“The first modern time ball was erected at Portsmouth, England, in 1829 by its inventor Robert Wauchope, a captain in the Royal Navy.”

The BBC News website has an article referencing Wauchope with interesting details (would you expect me not to follow this rabbit hole?). According to that article, Wauchope’s first idea was a system of flags that would be visible at sea to help mariners calculate their position by knowing the accurate time. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-humber-58559814

He first began soliciting interest in his “modernized” idea in 1818. His proposal, Plan for ascertaining the rates of chronometers by signal, described the time-ball, a large hollow metal sphere rigged on a pole and attached to a mechanism so that it might be dropped at an exact time each day. The ball installed in Portsmouth was the first test of his idea.

Wikipedia says: “Others followed in the major ports of the United Kingdom (including Liverpool), and around the maritime world.” The one on the Nelson Tower in Edinburgh is shown below.

“One was installed in 1833 at the [Greenwich Observatory] in London by the Astronomer Royal, John Pond, originally to enable tall ships in the Thames to set their marine chronometers, and the time ball has dropped at 1 p.m. every day since then.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Observatory,_Greenwich)

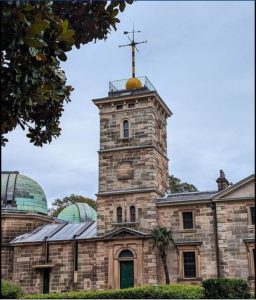

Except in windy weather, according to a source in the BBC article. The pole in Greenwich is relatively weak and strong wind is a hazard. In 1853, the Greenwich pole broke and the huge ball crashed to the ground! (In this photo it looks to me as though the pole may have since been reinforced!)

When American and French ambassadors visited England, Wauchope also submitted his idea to them. The United States Naval Observatory was established in Washington, D.C., and the first American time ball went into service there in 1845.

Wikipedia describes the process: “Time balls were usually dropped at 1 p.m. (although in the United States they were dropped at noon). They were raised half way about 5 minutes earlier to alert the ships, then with 2–3 minutes to go they were raised the whole way. The time was recorded when the ball began descending, not when it reached the bottom. With the commencement of radio time signals (in Britain from 1924), time balls gradually became obsolete and many were demolished in the 1920s.”

New York City’s contemporary version of the time-ball has been used since 31 December 1907 at Times Square as part of its New Year’s Eve celebrations. Quoting Wikipedia again, “At 11:59 p.m., a lit ball is lowered down a pole on the roof of One Times Square over the course of the sixty seconds ending at midnight. The spectacle was inspired by an organizer having seen the time ball on the Western Union Building in operation.”

The article also says only 60 of these time balls still remain in locations around the world –I found it interesting that eight are in the United Kingdom, seven are in Australia, including one at the Sydney Observatory (shown below), three are in the United Sates and three in New Zealand.

Belated wishes for a Happy New Year, everyone!

P.S. A shorter version of this article was posted on Facebook, in the readers’ group “Regency Kisses: Lady Catherine’s Salon.” I’ve mentioned the group here before –it is focused on “sweet/low heat” Regency romances and authors, so if you are on FB and read all types of Regencies, you might like to take a look. It is a great place to discover new authors to try, while waiting for the next books to release from your “Risky Regency” writers here!