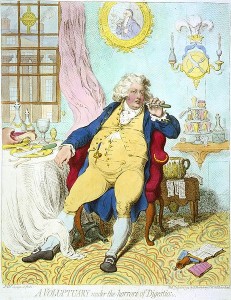

This weeks selection from my library shelves is Royal Poxes & Potions by Raymond Lamont-Brown. It gives us an interesting picture of Royal doctors from medieval times to the present day. Let’s take a look at our period. HRH George Augustus Frederick, Prince of Wales was (as we well know) a tad pudgy in adulthood. In fact, we learn from this book, that an inclined plane was constructed on which Prinny was placed in a chair on rollers and moved to the platform which was then raised high enough to pass a horse under and let HRH gently down into the saddle.

During the period from 1787 to 1796, the Prince of Wales’s medical household included Sir Gilbert Blane, Richard Warren and Anthony Addington, later joined by Sir Walter Farquhar and John Latham. These doctors recorded not only the prince’s obesity and his craving for women and food, but the character traits of “vanity, extravagance, self-indulgence, and undependability.” Is anyone who has read a Regency Romance surprised by this? I think not. As the Prince Regent’s “physician-extraodinary,” Blane records treating Prinny for a sprained ankle, incurred while teaching his daughter Charlotte how to dance the Highland Fling. This could not have been an easy task for a man of Prinny’s girth and Blane recommended that he “curb his eating and keep more regular hours.” This advice was, naturally, ignored. Sir Astley Paston Cooper, who had studied medicine at London, Edinburgh, and Paris, was awarded a knighthood for successfully removing a sebaceous cyst from the Prince Regent’s scalp. Sir William Knighton appears to have been the physician most highly regarded by the prince and who became the King’s physician when Prinny became George IV. By 1822, he was also private secretary and keeper of the privy purse and one of the king’s closest confidantes. Those around the king attributed Knighton’s success largely to sycophancy. During a tour of Scotland, the king suffered from gout, the pain of which “no amount of cherry brandy succeeded in dulling.” Knighton treated him with a “mixture of flattery, laudanum (to which the king was addicted), bleeding and the potions of the day.”

The king had been seriously ill since the beginning of 1830. The royal physicians diagnosed “ascites (abdominal dropsy) and logged his difficulty in breathing, hiccups and bilious attacks.” He died on June 26, 1830 in extremely poor shape despite the attendance of at least ten royal physicians during the course of his adult life. The post-mortem, conducted by Sir Astley Paston Cooper, revealed that “His Majesty’s disorder was an extensive diseased organisation of the heart; this was the primary disorder, although dropsical symptoms subsequently supervened, and in fact there was a general breaking up of his Majesty’s constitution.” The report goes into quite a bit of detail which I’ll not inflict on you here. But, if you’re interested, it’s all in the book along with much information about the doctors of George the IV and the monarchs who preceded and succeeded him.

So the question becomes whether he had a bunch of blocked arteries….or congestive heart failure.

Thanks for another interesting post, Myretta. I especially love the description of how they got Prinny onto a horse.

So basically the man was indulged to death. Fascinating post as always, Myretta, and another book to add to my wish list!

Poor horse!!