References to Valentine’s Day go back to early times. Chaucer mentions it, and so does Shakespeare. By the 1600’s, giving gifts or tokens to ladies seems to have become a common practice, mentioned by the diarist Samuel Pepys.

During the Regency era, parties and cards as we think of them now still were not part of celebrating Valentine’s Day, but unmarried admirers did send tokens, hand-made cards, letters, verses from poetry, etc. In fact, it seems that for young swains courting young ladies, such recognition of the day was de rigueur. No pressure, right?

To help those who lacked a talent for composing poetical messages, publishers were quick to fill the void, issuing pamphlets like The Young Man’s Valentine Writer (1797), filled with romantic verses which could be copied out by those with little poetic skill and sent to their sweethearts.

That sending such missives and cards was common practice seems clear when we consider this tidbit from the Morning Chronicle of February 15, 1815:

“Yesterday being Valentine’s day, the whole artillery of love was put into requisition. The Postmen were converted into Cupids, and instead of letters upon business, carried epistles full of flames, darts, chains, and amorous declarations.”

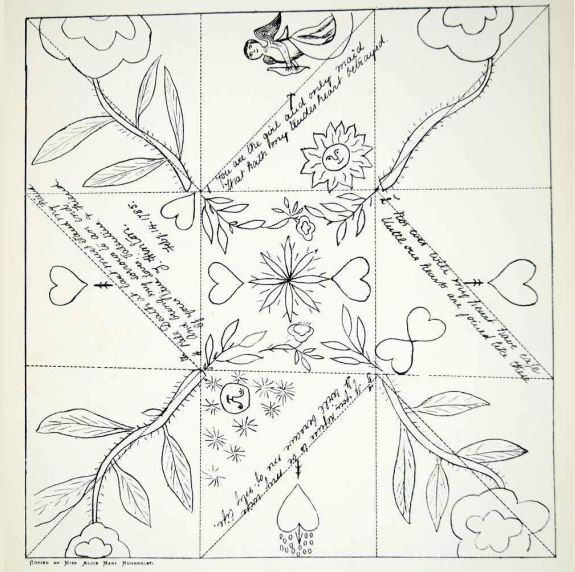

Before the advent of machine-made cards, what would a Georgian or Regency Valentine have looked like? Here is an example of the folded paper “puzzle-purse” style of Valentine, dated February 14, 1816.

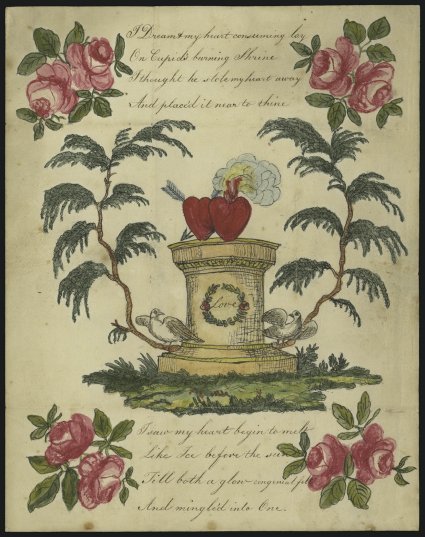

Below is another example of a typically folded hand-made paper card, decorated with watercolor, from Edmund Hemming to Anne Wilkes of Bidford-on-Avon, Warwickshire, dated 14 February 1820, courtesy of English Folk Art.

The design features hearts & arrows, flowers, and lovebirds. The main central design, when unfolded, shows the fashionable young couple in arms, standing beneath two trees (symbolically entwined), with a house on the left (a happy home), and a church on the right (wedding bells).

The love token includes romantic verse, ‘On you depends my future peace, One kindest look one tender sign, Shall bid my every trouble cease, Come then and be my Valentine’.

However, there were all sorts of craft approaches: pinwork (piercing paper to make the designs), cutwork (like making paper snowflakes, cutting the paper to make it have lacey designs), quill-work, and also non-paper options, to create love tokens made of any kind of material you can think of! The one at left is just lavishly illustrated in watercolors.

If you are ambitious or creative enough to want to try to make a Regency-style Valentine, I found the patterned examples below which were copied in the 1880’s from Georgian Valentines, one dated 1785. There were no directions, so you’ll have to sort out the fold lines and the order in which to make the folds for yourself. If you have experience doing origami, that will undoubtedly help!

Paper was expensive in this period, and so was postage. And there were no envelopes! You might find this video about letter-folding in the Regency helpful! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qwyEERi-hyA

I hope you enjoyed this glimpse of true romance in our favorite time period. Whatever your pleasure, I wish you a Happy Valentine’s Day!

What lovely tokens! I suppose the couples all got married, as failed courtships rarely result in the woman saving her unwanted swain’s paper artifacts.

Hi Susan! Thanks for responding, even though for some weird reason we haven’t been able to fix, the site isn’t displaying comments these days! Interesting assumption, yet in fact, the English Folk Art example from 1820 has a story with it, which explains that Edmund Hemming was not successful in his courtship and Anne Wilkes actually married someone else. Tantalizingly incomplete –he might have died rather than been thrown over, but either way it’s sad!! And interesting that the valentine was saved. Spurs the imagination!!

[…] (and in some locations, children) during the Regency period, and in a post in this space last year (here) I talked about the types of cards and mementos that might be exchanged, including the fascinating […]