In my internet perusing I came across this post at one of my favorite websites: Letters of Note.

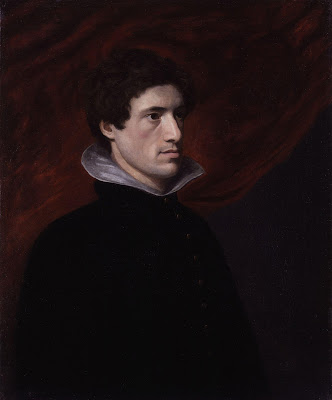

Picture via Wikemedia. Charles Lamb by William Hazlitt

Two things:

One: Lamb was a hottie.

Two: He could wax effing eloquent about a cold. Who among us hasn’t felt like this:

If you told me the world will be at an end to-morrow, I should just say, “Will it?” I have not volition enough left to dot my i’s, much less to comb my eyebrows; my eyes are set in my head; my brains are gone out to see a poor relation in Moorfields, and they did not say when they’d come back again; my skull is a Grub-street attic to let—not so much as a joint-stool or a crack’d jordan left in it; my hand writes, not I, from habit, as chickens run about a little, when their heads are off. O for a vigorous fit of gout, cholic, toothache&-an earwig in my auditory, a fly in my visual organs; pain is life—the sharper, the more evidence of life; but this apathy, this death!

Dude. That was one miserable cold. Go read the entire letter.

Here’s one of his poems:

A Timid Grace Sits Trembling in her Eye

A timid grace sits trembling in her eye,

As loath to meet the rudeness of men’s sight,

Yet shedding a delicious lunar light

That steeps in kind oblivious ecstasy

The care-crazed mind, like some still melody:

Speaking most plain the thoughts which do possess

Her gentle sprite: peace, and meek quietness,

And innocent loves, and maiden purity:

A look whereof might heal the cruel smart

Of changed friends, or fortune’s wrongs unkind:

Might to sweet deeds of mercy move the heart

Of him who hates his brethren of mankind.

Turned are those lights from me, who fondly yet

Past joys, vain loves, and buried hopes regret.

And another

A Parody

Lazy-bones, lazy-bones, wake up and peep;

The Cat’s in the cupboard, your Mother’s asleep.

There you sit snoring, forgetting her ills:

Who is to give her her Bolus and Pills?

Twenty-five Angels must come into Town,

All for to help you to make your new gown-

Dainty aerial Spinsters & Singers:

Aren’t you asham’d to employ such white fingers?

Delicate Hands, unaccustom’d to reels,

To set ‘em a washing at poor body’s wheels?

Why they came down is to me all a riddle,

And left hallelujah broke off in the middle.

Jove’s Court & the Presence Angelical cut,

To eke out the work of a lazy young slut.

Angel-duck, angel-duck, wingèd & silly,

Pouring a watering pot over a lily,

Gardener gratuitous, careless of pelf,

Leave her to water her Lily herself,

Or to neglect it to death, if she chuse it;

Remember, the loss is her own if she lose it.

A Dramatic Fragment

‘Fie upon’t!

All men are false, I think. The date of love

Is out, expired, its stories all grown stale,

O’erpast, forgotten, like an antique tale

Of Hero and Leander.’

-John Woodvil

All are not false. I knew a youth who died

For grief, because his Love proved so,

And married with another.

I saw him on the wedding-day,–

For he was present in the church that day,

In festive bravery decked,

As one that came to grace the ceremony,–

I marked him when the ring was given:

His Countenance never changed;

And, when the priest pronounced the marriage blessing,

He put a silent prayer up for the bride–

For so his moving lip interpreted.

He came invited to the marriage-feast

With the bride’s friends,

And was the merriest of them all that day:

But they who knew him best called it feigned mirth;

And others said

He wore a smile like death upon his face.

His presence dashed all the beholders’ mirth,

And he went away in tears.

What followed then?

O then

He did not, as neglected suitors use,

Affect a life of solitude in shades,

But lived

In free discourse and sweet society

Among his friends who knew his gentle nature best.

Yet ever, when he smiled,

There was a mystery legible in his face;

But whoso saw him, said he was a man

Not long for this world–

And true it was; for even then

The silent love was feeding at his heart,

Of which he died;

Nor ever spoke word of reproach;

Only, he wished in death that his remains

Might find a poor grave in some spot not far

From his mistress’ family vault-being the place

Where one day Anna should herself be laid.

I keep forgetting how much I like poetry. It’s good to be reminded.