We’ve been talking about private weather diaries from the extended Regency period, particularly the hand-written volumes that have been preserved in the library archives of the UK’s Meteorological Office. Several have been digitized: https://digital.nmla.metoffice.gov.uk/SO_fc1807c0-03db-49d8-a160-52fac26ded34/

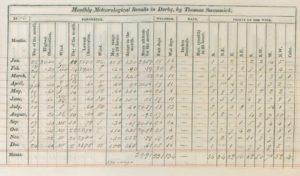

My initial interest was specifically a diary by John Thomas Swanwick of Derbyshire, kept 1793-1828, but it grew exponentially from there (see Part 1 of this article, posted March 13).

My initial interest was specifically a diary by John Thomas Swanwick of Derbyshire, kept 1793-1828, but it grew exponentially from there (see Part 1 of this article, posted March 13).

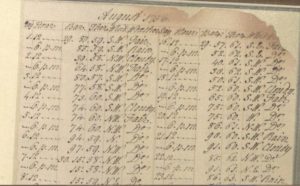

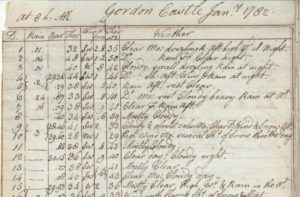

The next set of diaries records 80 years of weather in Modbury, Devonshire, 1788-1868, at the opposite end of the UK from Gordon Castle in Scotland. The diaries were kept by a father, John Andrews Sr., to 1822, and by his son John Andrews to 1868. Handwritten notes at the front of the diary indicate that the diaries were “offered to the Meteorological Society” by the son and accepted in June of 1868.

Only informal notes fill the first two months, but starting in March, 1788, Andrews recorded barometer and thermometer readings in hand-drawn columns along with commentary. The handwriting is not so fine a hand, and readings are not reported consistently. At the end of 1789, he reported the days, month-by-month, that “Moore’s Almanac” predicted rain or snow would fall, within a day one side or the other. We assume this was so he could compare for accuracy?

These diaries each cover two years. In 1790 Andrews began to be more regular about including the barometer readings and began to record twice daily, at 8am and 10pm, although temperatures are still missing. He clearly doesn’t have all the weather-recording instruments that some of the other diarists use. On December 14, 1790, he began to include temperatures again, but notes his dissatisfaction with the accuracy of the thermometer. By 1791, Andrews was including three barometer reports each day, at 8am, noon, and 10pm, and had shifted the format from using the pages normally to a vertical form running down two pages turned sideways.

Hygrometers

On March 15, 1790, he begins to include hygrometer readings (humidity), which were also included in Dr. Hughes’s Stroud diary. Andrews notes how he has kept a separate account of it since October when it was first put up, and has noticed it shifting “considerably” towards the “0” marking the median between moist and dry on the dial. He does not say what kind of hygrometer it is, but it seems likely it might have been one of the whalebone and human hair types invented by either Jean-Andre Deluc or Horace-Benedict de Saussure, who both developed them around 1783, just seven years earlier (pictured below). The metal ring appears to be the “dial” with measurement markings on it.

Deluc’s c. 1783 whalebone and hair hygrometer, By Rama, CC BY-SA 3.0 fr, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=68763240

The later diaries also appear to be hand-made or created using pre-lined accounting books. One kept by a woman, Caroline Moleworth, in Cobham, Surrey, 1825-1867, includes notes on barometer readings and two thermometers, “in the vestibule” and “in the window of the library”—which tells us she was well-to-do to own the equipment and also have a large enough house to include a library.

Storm Glasses

Interestingly, Caroline also had a “storm glass,” an old method of predicting storms via chemical solution inside a glass globe. She proudly calls hers a “Tagliabues storm glass.” Cesare Tagliabue Jr. (1767-1844) expanded his family’s instrument business by opening a firm in London in 1799 to produce thermometers, barometers, and hydrometers (which successive generations expanded further), so this is likely the source.

Storm glass 1825 advertisement (By Jeffery Dennis -Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=58907604)

In 1825, Caroline was using it well before the fad for them in mid-century led by Vice-Admiral Robert Fitzroy of the HMS Beagle, who used a storm glass extensively on his sea journey explorations and promoted their use. Her diary includes occasional observations when she notes changes in its appearance.

Storm glasses are still available today. Fitzroy is credited with popularizing the accepted “reading” chart still in use.

He is considered a “pioneering meteorologist who made accurate daily weather predictions, which he called “forecasts”. In 1854 he established the Met Office, and created procedures to pass weather information to sailors, fishermen and other mariners for their safety.” (Quoted from Wikimedia Commons)

The accuracy and the method by which these storm glasses work are still debated today. One theory is that the earlier glasses were not well sealed and were affected more by air pressure, like a barometer, and today’s tightly sealed ones are affected more by changes in temperature. A good source for more information on these (besides Wikipedia) is: https://www.weatherstationadvisor.com/what-is-a-storm-glass/

Storm glass picture (By Brudersohn – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=19588028)

John Thomas Swanwick was born in 1792 in Derby, so it seems certain that it had to be his father, Thomas Swanwick, a schoolmaster, who first started keeping that Derbyshire weather diary. Thomas, born in 1754, would have been 39 years old when he began it. John Thomas, the middle child of three, no doubt grew up watching his father enter data into that diary faithfully every day. At some point, John Thomas, the son, had to have taken it over, for his father died in 1814 at the age of 60 and the diary continues for another 14 years.

At age 41 in 1833, John Thomas Swanwick married a widow, Isabelle Hall. At the time of his marriage his occupation is listed as schoolmaster, like his father. Did he step into his father’s shoes professionally as well as in taking over the weather diary? Did he postpone marriage while tending to his mother?

Derby was a major market town in Derbyshire, with a population of 11,000 in 1801. The family attended All Saints Church, which later became Derby Cathedral. Derby School (aka Derby Grammar School), founded by Queen Mary Tudor in 1554, stood in St Peter’s Churchyard.

Did the Swanwicks teach there? Since we don’t know where either Swanwick taught, we also cannot know if it was a full-time occupation or whether they were gentlemen farmers on the side. The diary stops in 1828, five years before John Thomas Swanwick married.

This diary is fragile and has not been digitized. I was fortunate to obtain some pdf images of the pages I needed through the kindness of the Met Office library archives staff, Mr. Duncan Ball in particular. It does seem the printed templates of the Swanwick diary were custom-designed by the writer and commissioned privately from the printer—none of the other diaries are so elegant.

Did the son faithfully recopy his father’s data into a new book, one he had pre-printed with templates that captured all the categories roughed out in an earlier version? Or did the father have it done? The printed headers say Thomas Swanwick up until 1802, and then John Thomas Swanwick after that. The handwriting does appear to change at that time, and is not as perfect. John Thomas would have been 9 years old. Was he deemed old enough for his father to start teaching him to keep the diary then?

Perhaps the schoolmaster bartered some lessons in return for the extravagance of the custom printing job. Or perhaps Thomas Swanwick was highly paid. The beautiful quality of the father’s handwriting in addition to the finely detailed organization and presentation of that particular diary certainly suggest a high level of training and competence.

I had less luck tracing information about the other diarists. Two John Andrews of similar age lived in Modbury, Devon, baptized within 6 years of each other and married to different women within two years of each other. I could not pull marriage records in detail that would have told me their professions.

Dr. Thomas Hughes of Stroud was probably a clergyman who died in 1815, but there is almost no record of him other than his marriage “c. 1780.” Another Thomas Hughes of Stroud left a will probated in 1813, so he died that year or earlier. He was a surgeon, so at that time would not very likely have been recognized as “Dr.” or been as well-educated as a clergyman, but I would need access to the will to know more.

Taken together, the evidence suggests all of these diary keepers (except for Caroline Moleworth) were educated, well-to-do men with a scientific, scholarly interest in studying weather rather than the purely practical interest of those managing the land. Further research into the identity and lives of each of these diary writers might not prove that conclusively—all we can do is speculate. Caroline was clearly interested in weather science as well as other natural phenomena –her diary includes notes about animals seen and flowering plants in bloom as well as weather.

Advances in weather forecasting were slower than progress in some other fields. As late as 1888 and 1889 the Council of the Meteorological Office requested lectures to be given at various British ports on the use of the barometer for seafarers. In 1890 the lectures were published as “Weather Forecasting for the British Islands by means of a barometer, the direction and force of wind and cirrus clouds”.

The Meteorological Society to whom the Modbury diaries were donated wasn’t formed until 1850, well after the Regency period and just four years before the national government office was established. It was granted a royal charter in 1866, and went on to become the Royal Meteorological Society in 1883.

However, the fifteen science-minded men who founded it were also astronomers and versed in other overlapping sciences as well. Many were Regency-era members of the Astronomical Society of London, which was founded in 1820. Interest in science blossomed in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, and that interest included weather. Who knows how many other weather observers in those early periods were watching and keeping records that are lost to us now?

Many thanks to the Library & Archives of the UK Meteorological Office for helping me with research and setting me off down this deep rabbit hole. I hope those of you who read all this have enjoyed the trip! If you did, perhaps you’d be so kind as to leave a comment. 🙂