As you know, one of my favorite 19-th century illustrators & PUNCH-men is Richard Doyle, who joined the staff of the magazine when he was just 19 years old, and who designed the iconic cover of PUNCH just a few months later. I still have very fond memories of that magical day I spent in the Victoria & Albert Museum, looking through Doyle’s sketchbooks. (YES!!!! I touched the original sketchbooks! The sketchbooks Doyle himself had touched!)

However, there is one kind of primary source related to Richard Doyle that has remained unpublished for many years and of which you can catch only occasional glimpses in books about Doyle: the illustrated letters he sent to his father in the early 1840s. These were part of the weekly challenge John Doyle set for his sons: in those letters they were to describe what they had seen and done that week. Doyle senior encouraged them to go to the theatre and attend other important cultural and political events in London.

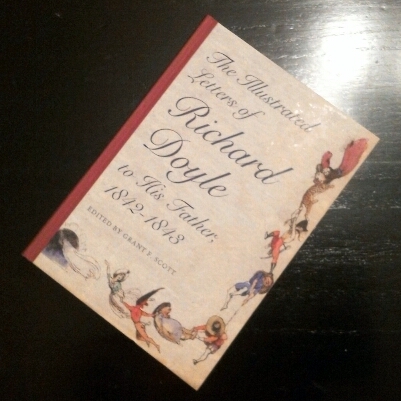

A couple of weeks ago, I found out – quite by accident! – that for the first time ever there’s a scholarly edition of Richard Doyle’s illustrated letters (at this point, imagine me melting into a puddle of delight). So of course, I had to have that book. And, OH MY GOSH, those letters, they are wonderful! I haven’t yet had time to really delve into it, but even just browsing through it is a delight.

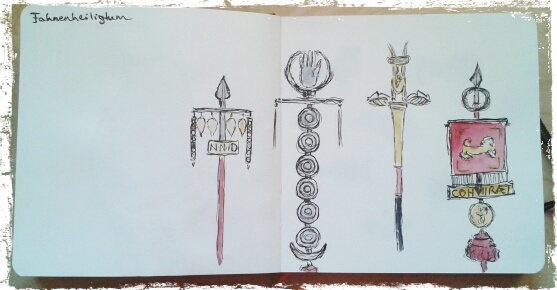

Doyle presents to the reader street scenes of London and also takes us into the Doyle home, where he shows us his brothers and himself hard at work at the next painting for their private Sunday exhibition. There are fantasy scenes with fairies and, of course, there plenty of little knights too – one of Doyle’s most favorite theme in those years and one that should later make his illustrations favorites with the PUNCH readership.

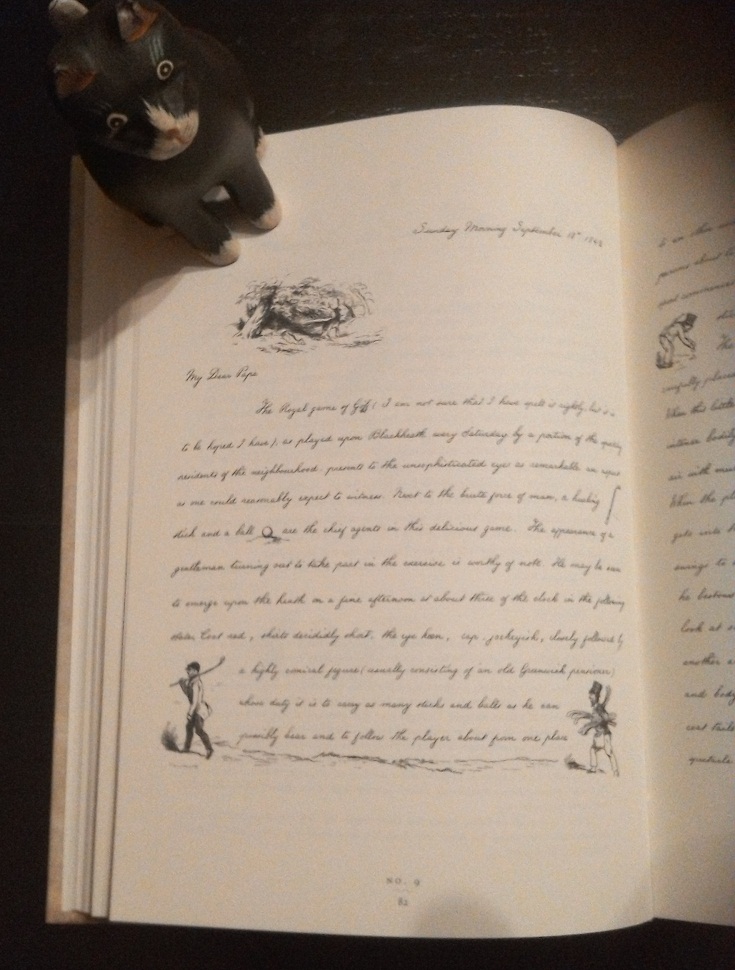

The letters are whimsical and charming. Take the one from 18 September 1842, which opens with,

My Dear Papa,

The Royal game of Golf (I am not sure that I have spelt it rightly, but it is to be hoped I have), as played upon Blackheath every Saturday by a portion of the sporting residents of the neighbourhood, presents to the unsophisticated eye as remarkable an aspect as one could reasonably expect to witness. Next to the brute force of man, a hurling stick and a ball are the chief agents in this delicious game.

By December 1843, Richard Doyle was working for PUNCH and the new job is taking up much of this time – to the extent that he fears he won’t be able to finish the “Christmas things” promised to friends and family. “On the next page,” he writes to his father on 17 December in the last letter of the collection,

you will find a representation of your son, precisely as he appeared at the moment when he gave up all hope, on Monday last, half past nine o’ clock p.m. […] The demon Punch perched upon the table, in exultation, points to the “Procession,” his “Christmas Piece.” Harlequin &c, as indicative of Christmas, weep over the little quantity of yours, a crowd of little urchins, in the foreground, by referring to the productions of former years, prove what can be done, and others in the back are plainly showing that it was not for want of paper.

As it turned out, Doyle would always find it difficult to meet deadlines (*cough* a little bit like myself…) – and it was never for want of paper!

In short, my new research book is a true delight, and I shall peruse it with much joy.