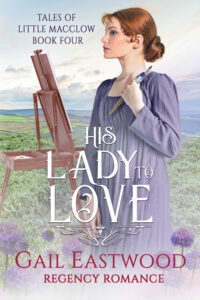

I am very excited to announce that the fourth book in my Tales of Little Macclow series, His Lady to Love, releases this coming Sunday, September 15th! After the year+ long detour I took to co-author Writing Regency England, I’m so happy to be back to my little Derbyshire village and the fiction stories of my heart.

Here’s the link (it’s also going to be in KU): https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0DDRKCFH3

The heroine of His Lady to Love, Ailis Murray (known to her intimate friends as “Lissie”), is a young Scottish widow. Many of the widowed heroines we meet in romance fiction have not enjoyed a happy first marriage. I think the reason is simply that the heroine’s lack of previous emotional engagement makes the new romance easier to have the “first love” depth and intensity readers enjoy. But I always like a challenge and frequently prefer to swim against the current. What if our heroine doesn’t fit that mold?

The heroine of His Lady to Love, Ailis Murray (known to her intimate friends as “Lissie”), is a young Scottish widow. Many of the widowed heroines we meet in romance fiction have not enjoyed a happy first marriage. I think the reason is simply that the heroine’s lack of previous emotional engagement makes the new romance easier to have the “first love” depth and intensity readers enjoy. But I always like a challenge and frequently prefer to swim against the current. What if our heroine doesn’t fit that mold?

Lissie loved her first husband deeply and after a year is still grappling to some extent with her grief. She is very resistant to falling in love again. She believes that she has “had her one great love” and isn’t willing to settle for a less satisfying relationship. She doesn’t want to wed again. (Naturally I hope the reader will be rooting for her to be proven wrong!) But the emotional risk is not her only reason for not wanting another marriage.

To understand the potential benefits of widowhood in the Regency, we need to take a quick look at what it meant for women to be married.

Marriage in Georgian and Regency society was considered the ultimate point of womanhood. Procreation was necessary for the continuation of society. In the upper classes, children meant maintaining the structure of the ruling strata of society, while in the lower classes, they meant maintaining the supply of workers in the laboring strata. But also, in these periods, the alternatives for women were few. Being married meant survival and sustenance—being protected and provided for by a man.

I think it is very hard for us in this modern age to fully grasp how different things were for women back then in an entirely male-dominated world! The trade-off for the life-long sustenance and (assumed) safety of marriage was that wives had no rights of their own. Legally, marriage was seen as unifying the couple into a single entity. Once married, everything a woman owned, earned, or was given belonged to her husband (unless protected in some way, such as a trust). A wife was legally dependent on her husband for everything, seen as essentially a sub-unit of the man she is attached to.

Obviously, there were women who defied the system, but they were the rare cases. And if widows hadn’t adequate means of support from some source after their husbands died, marrying again was the necessary alternative to suffering in severe poverty. But widows who had an income source, having fulfilled society’s expectations by marrying, could enjoy a freedom that no wives, spinsters, or younger unwed misses were granted. For widows, marrying again meant giving up their freedom and submitting themselves back into the legal invisibility of being a wife.

Lissie is a wealthy widow. Her late husband, who owned multiple properties including estates, undeveloped land, shipping interests, and even a woolen mill, left everything to her. And immediately, despite her mourning, suitors flocked to her. The wealth attracted them but also society assumed a woman had not the skill or intelligence needed to manage such assets. Except Lissie has already been managing all of it, for her husband was ill the last two years of their marriage and trained her in the job.

If she marries, all of her husband’s legacy goes to her new husband. Lissie has dreams and ambitions of her own, ones she expects a husband would not support. So she has practical as well as emotional reasons for resisting our lovely story hero.

I hope you’ll want to see how this romance works out! Our hero has dreams of his own and marriage is not a good fit in his immediate future, although this is a romance where he falls first. How does Scottish Lissie come to be in the English village of Little Macclow, anyway? And how does our hero entice her away from the solitary existence she seeks to get her involved with the affairs of the village?

The books in my series follow a continuing chronology and characters from the earlier books pop up again in later ones, but each book is written to stand alone, so you don’t need to have read the earlier ones to enjoy His Lady to Love even though it is Book #4. I am releasing it in Kindle Unlimited (temporarily). This release is the first time I’ve done that for any of my books, so if you’ve never read one and want to give my work a try, this is a good opportunity! I hope you will.

The books in my series follow a continuing chronology and characters from the earlier books pop up again in later ones, but each book is written to stand alone, so you don’t need to have read the earlier ones to enjoy His Lady to Love even though it is Book #4. I am releasing it in Kindle Unlimited (temporarily). This release is the first time I’ve done that for any of my books, so if you’ve never read one and want to give my work a try, this is a good opportunity! I hope you will.

Do you have any favorite stories with widowed heroines? Did they have good first marriages? Or after bad ones, are they either hoping for a better second chance or soured on the idea of marriage entirely? Have you had experience with any of these outcomes yourself?