Can you identify which of the following games (all of them ways of hitting a ball) would have been activities for Regency people and which would not? Tennis, baseball, rounders, nine pins, croquet, ground billiards, golf, cricket. Let’s take look at these and see how you did. Have you ever played any of these sports, or enjoyed Regency fictional characters who did?

TENNIS: “Tennis” is a catch-all term that actually covers two types of the game with separate but related histories. While our modern sport of “tennis” has roots that go as far back as medieval times, it actually developed from “lawn tennis,” a later offshoot of the form of the game known as “royal” or “real” tennis.

Royal tennis evolved from a 12th century monastic French game, “jeu de paume” (“game of the palm”), where the ball was hit with hands. Eventually, gloves were used, and by the 16th century when the game was at peak popularity, racquets were introduced and the game was being played on enclosed courts. But as we have already seen with lawn bowling, only the very wealthy could afford to build and maintain special venues for games—hence the name “royal” tennis. The intertwined history of royalty between England and France easily explains how the game arrived in England and gained popularity there.

Wikipedia dates the game in England to Henry V (1413–22). Sports enthusiast Henry VIII added sporting venues to his palaces, including tennis courts. Whitehall was said to include four indoor tennis courts, and the tennis court at Hampton Court Palace still exists. Mary Queen of Scots played tennis on a court at Falkland Palace in Fife which also still stands. But during the 18th century in England with the German-based House of Hanover on the throne, tennis fell out of royal favor, and in France the royal sport was doomed by the French Revolution, followed by the Napoleonic wars.

Although a reference to “field tennis, an invented game” is made by a memoirist from 1767, it was not until the 1870’s that “lawn tennis” came along, a version of the game that the general populace could play on smooth grass. As we have previously seen, the invention of the lawn mower no doubt played a key role in that evolution. So, tennis was played both before and after the Regency, but during the 18th and early 19th centuries it declined in popularity and is not a sport Regency folks would likely have played. They did, however, play racquets and squash racquets in very similar form to those games as known today.

CROQUET/Ground Billiards: Croquet is another game with ancient roots. Since croquet lawns in the 1870’s were venues for the first games of lawn tennis, let’s look at that quintessential summer game next. Croquet seems to have origins in either, or both, of two other games using balls, mallets and wickets. One is an earlier popular English game that, like tennis, has French origins—the game of pall mall (“paille-maille” in French), dating to the 13th century in France (using wickets made of wicker) and introduced in England in the 16th or 17th century (sources vary). The other root is the Irish game of “crooky” which by the earliest record dates from the 1830’s.

Thomas Blount’s Glossographia (1656) described pall mall as a game played in a long alley with wickets at either end, where the object is to drive a ball through the “high arch of iron” in as few mallet strokes as possible, or a number agreed on. Blount adds: “This game was heretofore used in the long alley near St. James’s and vulgarly called Pell-Mell.” (This is where the name of the famous London Street comes from.) The length of the alley varied, the one at St. James being close to 800 yards long. In 1854 an old ball and mallets were discovered, now in the British Museum, described thus: “the mallets resemble those used in croquet, but the heads are curved; the ball is of boxwood and about six inches in circumference.”

But how did pall mall evolve into croquet, a game with six or more wickets set in a pattern and spread over a much larger area than an alley? Or did it? An entire family of individually unidentified lawn games played in medieval times, collectively known today as “ground billiards,” were played with a long-handled mallet or mace, wooden balls, a hoop (the pass), and an upright skittle or pin (the king).” Any one of these games could have led to the development of “crooky” in Ireland, which locals are known to have played in 1834 at Castlebellingham. As with the earlier games, there is no record of the rules or method of playing.

However, a form of “crooky” was introduced in England in 1852. Isaac Spratt registered a set of rules for “croquet,” from a game he saw played in Ireland, around 1856. John Jaques published official rules and editions of croquet in 1857, 1860, and 1864 and manufactured sets. At first, croquet was played rarely, mostly by affluent or upper-class people. But the All England Croquet Club was formed at Wimbledon, London, in 1868. That same year the first all-comers croquet meet was held in Gloucestershire, England. Croquet became all the rage and spread quickly to all corners of the British Empire by 1870. Sad to say, croquet is thoroughly Victorian.

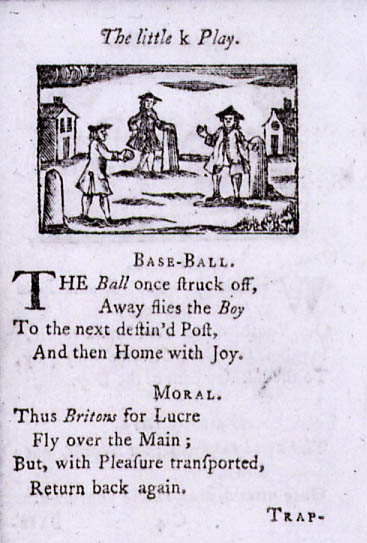

Baseball/Rounders: The earliest reference to rounders, which may actually date back to Tudor times, was made in A Little Pretty Pocket-Book (1744) and included an illustration of “base-ball,” depicting a batter, a bowler, and several rounders posts. The rhyme refers to the ball being hit, the boy running to the next post, and then home to score.

In 1828, William Clarke in London published the second edition of The Boy’s Own Book, which included the rules of rounders and also the first printed description in English of a bat and ball base-running game played on a diamond.

Rounders is very similar to the American game of baseball and is surely the ancestor of that game, evolved once brought across the pond. Clarke’s book including the rules and description was published in the U.S. in 1829, but English emigrants would have brought the game over with them far earlier. Rounders has been played by British children right up until modern times, so Regency children given the opportunity (most likely in the country or at school) would very likely have played the game. Would adults have played? Less likely, unless they were being particularly playful in re-enacting their childhood pursuits.

Ninepins/Skittles: Differing from lawn bowling, many lawn games involved rolling a bowl and hitting a pin or cone, or multiples of these. These games are the true ancestors of our modern day bowling. An early form of bowling was called “cones,” in which two small cone-shaped objects were placed on two opposite ends, and players would try to roll their bowl as close as possible to the opponent’s cone. The very old game of “kayles”—later called nine-pins, or skittles, after another name for the pins—usually involved throwing a stick at a series of nine pins set up in a square formation, although in some variations the players would roll a bowl instead. The object was to knock down all the pins with the least number of throws. Sometimes, the game would feature a larger “king pin” in the center of the square which, if knocked down, automatically granted a win.

Ninepins (1570s) or skittles (1630s) was generally played in an alley, like pall mall, and an arrangement of pins might stand at each end, or only at one. But it did not really require much more than a flat space of ground and became popular among all the classes, especially by the 18th century. Public houses with grounds often offered skittles accompanied by gambling, of course, leading the poor to become even poorer. Press gangs, too, found the pub-side ninepin alleys a fruitful place to gather men to serve the king.

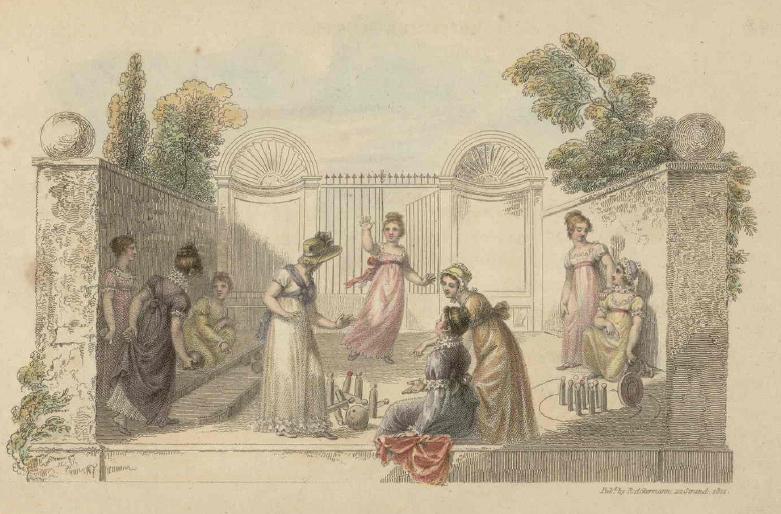

In the late 18th century, the moral outrage over the destructive effect of such gaming led to a movement to level the skittle grounds to counteract the problem. This merely led to the resurgence of another game, nine-holes (1570s), also known as “bumble puppy” later on. In this game, instead of pins to knock down, the object became to throw balls into nine holes (in a board or dug into the ground) arranged with successive number values and the player with the highest points won. Since this game wasn’t banned in the statutes against skittles or ninepins, the authorities could not stop the games. Eventually during the Regency, skittles reclaimed its popularity. (see illustration at top, from an 1822 book on exercise and sports for young women)

Cricket: There’s a theory that cricket, another “bats and ball game,” may have derived from a game like pall mall or bowling, by the intervention of a batsman stopping the ball from reaching its target by hitting it away. The game is so old it probably dates back to Saxon or Norman times in the southeast of England, but written references go back at least to 1590. The name comes from either Old French (criquet “goal post, stick”), Middle Dutch/Flemish (cricke “stick, staff”) or Anglo-Saxon (cricc “shepherd’s staff”).

By the early 18th century cricket had become a leading sport in London as well as the south-eastern counties of England with organized clubs and some professional county teams, and continued to spread slowly. The switch to throwing the ball instead of rolling it along the ground came sometime around mid-century along with the change to straight bats instead of bent ones. Boys played cricket at schools, children played cricket in their villages, and adults of both genders apparently played as well. The first known women’s cricket match was played in Surrey in 1745. The famous Lord’s Cricket Ground opened in 1787 with the formation of the Marylebone Cricket Club. Interest in cricket has not waned from that time to the present day, so it was certainly being played during the Regency.

GOLF: Golf is another stick-and-ball game with roots in those early and unknown ancient lawn games. While the specifics of golf were developed by the Scots, the roots of the game (and even some of the early wooden balls used to play the game) came to them from the Dutch. The name “golf” is derived from the Dutch word “kolf” which means club. A Dutchman first described the game of golf in 1545, while it first appeared in Scottish literature in 1636, but there are other references to the Dutch game as early as the 13th and 14th centuries.

It was the Scots, however, who had the idea of making holes in the ground, laid out over a course, and made the object of the game to get the ball into each of those holes.

Golf has an interesting history, but it evolved quite steadily over time in Scotland with the exception of being banned by James II (1457), James III (1471) and James IV (1491) for distracting the military from training. James IV reversed his ruling by 1502, however. It seems the Scottish king was fond of the sport himself. Later in that century, King Charles I brought the game to England and Mary Queen of Scots introduced the game to France.

The Old Course at St Andrews, Scotland is one of the oldest courses dating to 1574 or possibly earlier. Diarist Thomas Kinkaid mentioned some rules in 1687, but the first “official” rules were not issued until 1744. James VI played golf at Blackheath near London in 1603 when he became James I of England, where the Royal Blackheath Golf Club was later established (1745 or earlier). Two English courtiers played against James VII of Scotland in 1681 at Leith for a wager, but there is little evidence the English took to the game until the Victorian era. But if you had a Scottish character in Regency London, he might be happy indeed to play at Blackheath if he were accepted as a member or knew someone else who was.

“Golf is an exercise which is much used by a gentleman in Scotland……A man would live 10 years the longer for using this exercise once or twice a week.”–Dr. Benjamin Rush (1745 – 1813)

(illustrations in this post are public domain, as vintage art)