In story-telling, we are always warned not to start with the weather. That is exactly the recurring joke in the Peanuts cartoon when pup Snoopy’s novel always begins, “It was a dark and stormy night”(although doesn’t that at least make you expect something dramatic is going to happen?). But weather plays an important role in story settings, and can be an effective tool to drive events in plot. Ignore it and your story can fall flat.

Weather forecasting today is a fine science we all rely on and I dare say also often take for granted until storms or other potential disasters threaten. Obviously, in the Regency period there was no such service anyone could turn to. And given the agricultural basis of Great Britain’s economy at that time and the importance of sailing ships, weather played a very crucial role in the daily lives and the prosperity of the nation.

(https://yesofcorsa.com/bad-weather/)

The Industrial Revolution had begun by Regency times, but it would not reach full sway until Queen Victoria’s era. Weather might not affect the factories springing up in the north counties, but farming the land was still the backbone of both the economy and society at this time. Landowners and tenant farmers alike were dependent on getting the greatest yield they could from the acres under their care. That was very much tied to weather along with the fertility of the soil. And weather could certainly affect the transportation of goods from those factories in the north, or the safety of anyone in the path of floods or storms.

Were a reliance on folklore beliefs and an ability to “read” current conditions the only methods they could employ to predict what weather might lie ahead and to plan accordingly?

Research for my current wip, Book Four in my Little Macclow series set in Derbyshire (HIS LADY TO LOVE), has led me down a new rabbit hole to share with you—private weather diaries. There is a fine collection of these hand-written volumes that have been digitally preserved in the library archives of the UK’s Meteorological Office: https://digital.nmla.metoffice.gov.uk/SO_fc1807c0-03db-49d8-a160-52fac26ded34/

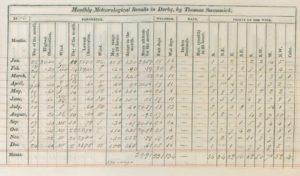

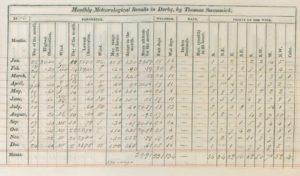

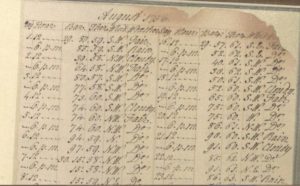

My initial interest was specifically a diary by one John Thomas Swanwick of Derbyshire kept 1793-1828. (My story happens in August of 1815). Comparing the August weather recorded in flawless handwriting across all those years gave me a good view of what it should be in my story. But I quickly became more interested in the diary itself, the man who kept it, and what it said about his discipline and daily habits. Also, this particular diary has what are clearly custom-printed templates, for both the yearly comparisons and the monthly observations. Was keeping a “weather diary” a special hobby, or a regular part of normal record-keeping? (click on photos to enlarge)

Sample page and printed headings in the Swanwick weather diary

I wanted to know–did Mr. Swanwick design this book and have it privately printed, or were such blank diaries available from printers for customizing? If the latter, then keeping weather diaries was something enough people did for printers to make a profit by offering such books. If the former, then Swanwick had to be a man of enough means to be able to afford such a bespoke product.

These questions led me to examine some of the other diaries in the Met Office archive collection that are available at the link above.

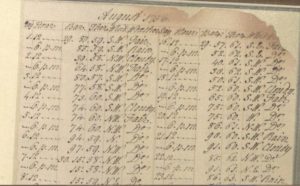

The earliest one dates from 1755-1775 in Exeter. A typewritten note in the front says it is probably the earliest extent account of twice-daily barometer and thermometer readings. The 12-column format of all the pages suggests that it might have been a type of readily available accounting book that the diarist, one S. Milford, adapted to his own use. Milford’s headings are: day, hour, bar., ther., wind, and “weather” (i.e. fair, cloudy, stormy, showery, rain), a much simpler system than Swanwick’s. Milford fit two days’ data across a single page.

Exeter Weather diary Aug 1756

Barometers and Thermometers

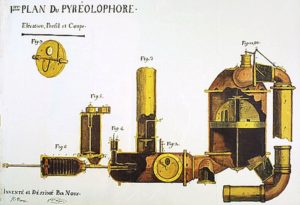

It is interesting to note that Milford and the other diarists generally owned both expensive barometers and thermometers and had the education to interpret them. Some seem to have also had hygrometers and sophisticated wind-measuring instruments. The barometer was invented in 1643 by an Italian physicist to measure atmospheric weight or pressure. Improvements by several more scientists turned it into the first “weather globe” and ultimately the more familiar barometer. The first thermometer was invented by Galileo, but a mercury-filled one similar to modern ones was invented in 1714 by physicist and inventor Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit. Jean-Andre Deluc, Swiss scientist who lived in England from 1773 until his death in 1817, was an advocate of the mercury thermometer over Galileo’s earlier alcohol-based versions. We don’t know which kind the diarists were consulting.

The next oldest diary goes from 1771-1813. Observations kept by Dr Thomas Hughes at Stroud, Gloucestershire, include other noteworthy events such as “storms, floods, earthquakes, aurora sightings and other geophysical data and occasional phenological remarks,” all indicating a man of some education. The book’s columns are ruled by hand, and the pages are set up to run vertically across two pages of the horizontal book turned sideways. The summary says his casual notes (kept in a dedicated column at the far right) “include reference to a number of historical events including the victory at Trafalgar and subsequent death of Admiral Nelson in the action.”

Sample page from the Stroud weather diary

More often, those notes expand on the “weather” observations. For instance, on January 3, 1771, he recorded cool and cloudy in the morning, then stormy with thunder and wind. The casual note says “a vessel on the Severn damaged by lightening.” On April 6, he noted snow still on some hills, the ground dry and grass withered “except in some moist places.” Hughes possessed a hygrometer in addition to his other instruments, reporting humidity readings among his other data.

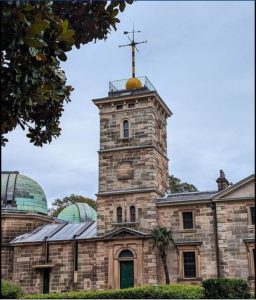

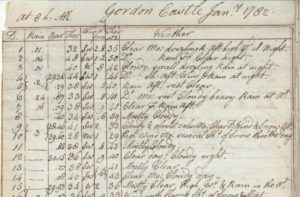

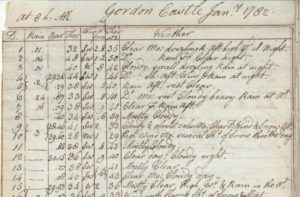

From 1781-1825 a set of diaries was kept at Gordon Castle in Moray Speyside, Scotland, “complete except for June and July 1812.” Who made the notes, the (original) 4th and 5th Dukes of Gordon themselves or more likely staff members assigned to the duty? This book, too, is hand-ruled, set up with five narrow columns at the left and a large space more than 2/3rds of the page reserved for the actual weather observations. Perhaps it is not surprising, given the Scottish location, that this diary includes first among its narrow standard columns the one labeled “Rain,” used to record the measured amounts.

Gordon Castle By John Claude Nattes 1804- National Library of Scotland Digital Gallery Shelfmark ID J.134.f, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org Rebuilt in 1769 for the fourth Duke of Gordon, the central four-storey block incorporated a six-storey medieval tower called the Bog-of-Gight, and was flanked by a pair of two-storey wings.

Also interesting—for the first year there is no barometrical data, and only wind direction. But starting in January of 1782, seven columns report date, rain, barom., therm (at 8am), wind (divided into direction and “force”), and therm again at 3(pm). Perhaps a barometer and some new wind measuring instrument had been gifts or purchases at the end of the previous year?

Gordon Castle diary sample page

There is a note at the end of this first month mentioning an “alteration” in when some of the data is noted and the addition of the wind force, but no mention is made of adding the barometric readings. By the next month, the 8am thermometer readings are marked “in” and “out” –did they acquire more thermometers, too? If “in” means inside, it is notable that the temperature in the castle runs generally only about 7-8 degrees warmer than outside, until the summer months when it is about the same, or cooler on the warmest days.

MORE TO COME

In Part Two (DEEP rabbit hole!): more diaries, more equipment, and investigations into the diary writers themselves. (will be posted on Thursday March 16)

The Pool of London by John Wilson Carmichael

The Pool of London by John Wilson Carmichael “Pool of London” by Thomas Luny (1801-1810)

“Pool of London” by Thomas Luny (1801-1810) “Pool of London, Below London Bridge” by Samuel Atkins (1790) at the Courtauld Gallery, London

“Pool of London, Below London Bridge” by Samuel Atkins (1790) at the Courtauld Gallery, London