Winter brings us the flu season (and COVID is still a threat), but with vaccines and modern medicine, the vast majority of us take it for granted we will survive.

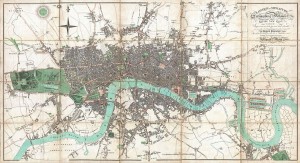

In the Regency era, though, influenza and other infectious diseases were often fatal. In 1775, an epidemic killed 40,000 people. It is not entirely clear if all the deaths were from what we know as influenza. Similar illnesses went by such names as the grippe, putrid fever, putrid infection, putrid sore throat. They might have included illnesses we know today as typhus, strep throat, Scarlet fever, pneumonia, diphtheria, or others.

Whatever illness, though, there was no effective cure for it.

Medicines like Edinburgh Powder or Daffy’s Elixir were advertised as cures, but were ineffective.

Regency era science had not yet learned exactly what caused the infectious diseases, nor exactly how they were spread. For example, it was not until 1909 that French microbiologist, Charles Nicolle, discovered that typhus was spread through body lice. Concepts of bacteria and viruses were unknown, although some illnesses were believed caused by breathing in “bad air.” It was also understood that one person could catch the illness from proximity to the sick person. In fact, the concept of quarantining was used as early as the 14th century to protect against plague.

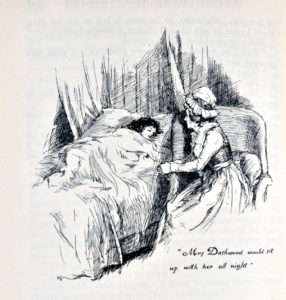

In Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, when Colonel Brandon rescues the rain-soaked, feverish Marianne, it sends pregnant Charlotte Palmer, the lady of the house, fleeing the house along with her husband and her servants, for fear of catching whatever fever from which Marianne suffers. Austen obviously realized illness could be contagious.

In addition to lack of effective medical treatment during the Regency, sewage was dumped in the streets, water was contaminated, and rodents and lice spread disease. In our modern age, we don’t worry about such things.

Thank goodness!!