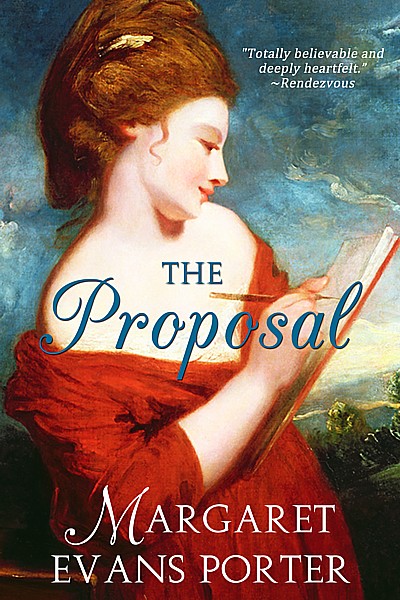

Today the Riskies welcome guest Margaret Evans Porter! Margaret and I have been friends since early days in my career, and I was a huge fan of her work even before that. The Proposal is one of my absolute favorites among her books, so I am very excited that a new edition will be released tomorrow!! Margaret is offering a print copy of The Proposal to a randomly chosen winner among those who comment by the end of this week, so please share your thoughts with us below after visiting here. And read on to find out about a new project she has coming out next month, as well!

Today the Riskies welcome guest Margaret Evans Porter! Margaret and I have been friends since early days in my career, and I was a huge fan of her work even before that. The Proposal is one of my absolute favorites among her books, so I am very excited that a new edition will be released tomorrow!! Margaret is offering a print copy of The Proposal to a randomly chosen winner among those who comment by the end of this week, so please share your thoughts with us below after visiting here. And read on to find out about a new project she has coming out next month, as well!

Margaret is the author of 11 novels and 2 novellas published in hardcover, paperback, digital editions, and in translation. She earned the Best New Regency Author award from Romantic Times Magazine with her first book, and later novels received multiple award nominations. She has also published nonfiction, poetry, and her photography, and is a trained actress who has worked on stage and in film and television. All this and she is also a historian and an avid gardener! But I should let HER tell you.

What’s the premise of The Proposal?

A: In 1797, Sophie Pinnock, a botanical artist and the widow of a famous landscape designer, is employed by the Earl of Bevington to alter the ground of his newly inherited castle in Gloucestershire. She would much prefer to restore the gardens to their original state than replace them. After many years living in Portugal, her employer has returned to England to claim his title.

Where did the idea for this particular story come from?

A: It was the dead of winter in New England, the world was buried under snow–much like this winter! My coping mechanism was to design new rose beds that would feature historic period roses from Medieval times to the Regency and Victorian eras. I had recently spent time at a Gloucestershire castle. I ended up with a 2-book contract as well as an expanded garden!

Where did you turn for research?

A: I had already amassed a collection of historic gardening guides and price lists from the 17th, 18th and 19th centuties. My mother is a rose gardener, so I was raised with historic roses and books about them. On trips to England I visited intact gardens from earlier times.

What aspects of the research itself most intrigued you?

A: There was a raging debate about landscape design at that very time, when Humphrey Repton was altering many formal gardens to conform with his more “natural” style–popular with some people, and criticised by others. I was able to rely on primary sources, like the Red Books that Repton created for his clients (Sophie provides her clients with Blue Books!) And I’m always happy when I can wander through English gardens, so that was particularly appealing to me.

Do you have a favorite scene in this book?

A: I managed to include a scene in which Sophie debates Humphrey Repton himself, because–quite conveniently–he had clients in the neighborhood.

What would you say is “risky” about this book?

A: It seems “risky” to us nowadays, the concept of a female businesswoman in the late 18th century or Regency. But there is so much precedent! Many a widow, through financial necessity or entrepreneurial desire, took on responsibility for her late husband’s businesses. I think it’s a disservice to these women to bury the record of their achievements, and in some cases their innovations–Mrs. Eleanor Coade, who developed Coade stone, Hester Bateman the Silversmith, Rolinda Sharples the artist, Mrs. Sarah Baker the theatre proprietress who developed the theatres of southeast England. These are the notable names, but how many more must there have been that we do not know?

Another aspect of “risk” concerns opium addiction, and to a lesser extent, attitudes and suspicions about sexual orientation. Both of which have an effect upon the secondary mystery plot.

How long have you been writing?

A: I’ve been writing stories since I could hold a crayon in my fist. I became a publisher-editor-author at age 9 or 10 when I founded a class newspaper. My family is packed with writers, so it wasn’t an unusual path for me to follow. My mother, who taught me to read quite young, says she always knew I would be a writer.

What aspects of your own personality show up in your stories?

I’m everywhere. I create gardens and grow roses–so does Sophie in The Proposal. I performed on stage for many years, and studied dance–I’ve written novels featuring an actress, a dancer, and an opera singer. Like Oriana in Improper Advances, I play the mandolin. I mine the places in Britain or Ireland where I’ve studied, lived and/or travelled and use them as settings for my stories. My dogs turn up in books as members of my characters’ households.

Do you find that your training in theater is helpful to you as a writer?

A: It’s immensely helpful, in a variety of ways. Performing period plays immersed me in the idiom of past times, I was speaking dialogue uttered by the people who lived in the eras about which I write. From a very young age I was required to do intensive character biographies, creating backstories for the people I was portraying–this often required in-depth research into social customs, education, upbringing, styles of speech, popular books and music. And of course I was wearing costumes–corsets, petticoats, full skirts, strange shoes–and carrying fans and having my hair dressed and so on. Those experiences were extremely valuable, as you might imagine!

Which book, if any, was the most difficult for you to write, and why?

I would say my new historical biographical novel, A Pledge of Better Times, for several reasons. It is entirely fact-based, all the characters were real people of the late Stuart court–monarchs and aristocrats.  Historical events provided the structure, the research was intense and took place over many years between other commitments. (For example, my productivity suffered a little during my 2 terms in the state legislature. But some sections of the novel were written surreptitiously during boring floor debates!) I don’t remember that any of my Regencies or historicals were difficult to write, although I did have to manage a very quick turnaround on an option book proposal while visiting friends in England. Almost every character in that book, Improper Advances, except the hero and heroine, were historical persons, so my fictional story needed to tie in with historical reality.

Historical events provided the structure, the research was intense and took place over many years between other commitments. (For example, my productivity suffered a little during my 2 terms in the state legislature. But some sections of the novel were written surreptitiously during boring floor debates!) I don’t remember that any of my Regencies or historicals were difficult to write, although I did have to manage a very quick turnaround on an option book proposal while visiting friends in England. Almost every character in that book, Improper Advances, except the hero and heroine, were historical persons, so my fictional story needed to tie in with historical reality.

You now have a second website (www.margaretporter.com) for your mainstream historical novels, featuring real people from history. Your April release, A Pledge of Better Times, is the first of these. Tell us a little bit about this new direction in your writing?

A: In my youth I read many YA biographical historical novels, and my ambition to write mainstream historical novels dates from that time. It took a long time for the right story to find me–that of Lady Diana de Vere, and of Charles Beauclerk, 1st Duke of St. Albans (bastard son of King Charles II and actress Nell Gwyn). It was sparked by some genealogical research, and caught fire after I became acquainted with a direct descendant of theirs. I spent years carrying out the research all round London–at Kensington Palace and Hampton Court and the Tower–as well as in Holland at The Hague and Paleis Het Loo. And Versailles. This book also features the development of formal gardens!

A Pledge of Better Times, will be available in print and as an ebook in April. It has just been named one of the “Books to Read in 2015” by the Book Drunkard blog–very exciting.

Where can readers go to get in touch or learn more about your books?

Website: www.margaretevansporter.com

http://www.facebook.com/AuthorMargaretEvansPorter

@MargaretAuthor on Twitter.

Risky readers, don’t forget to post a comment if you’d like a chance to win a print copy of The Proposal! Margaret Evans Porter, thanks so much for visiting with us today!

The Proposal:

When a lonely young widow and a mysterious earl clash over a neglected castle garden, suspicion and secrets threaten a blossoming love.

“Part romance, part mystery, a highly entertaining read.” –M.K. Tod, author of Lies Told in Silence

“Very sensual…lush in detail. Her characters have as much depth as the settings, and the gardens provide a wonderful backdrop for a tender love story.” –Affaire de Coeur

“Decidedly different…totally believable and deeply heartfelt.” –Rendezvous

Print on Amazon:

http://www.amazon.com/Proposal-Margaret-Evans-Porter/dp/0990742091

Kindle on Amazon: