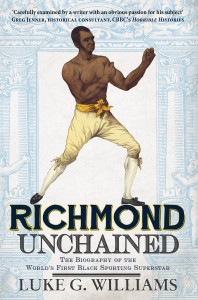

A book I’ve been waiting for is out! Naturally I bought it immediately. The author, Luke Williams, and I got in contact, and he graciously agreed to be interviewed here at the Riskies. I’m giving away a copy of his book to one commenter, rules below.

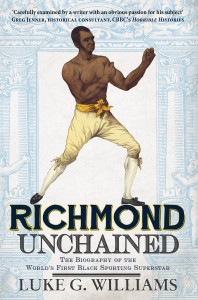

The book is Richmond Unchained, the Biography of The World’s First Black Sporting Superstar. Richmond was a boxer from the Regency era whose name would be encountered by any author doing research into boxing of the era. This is one of the most interesting, engaging biographies I’ve read in some time and I highly recommended it to anyone and everyone.

I’m not kidding you here, I stayed up late three nights running because I had to find out what happened. This is a well-written, meticulously documented, and completely engaging story of a man who deserves to be better known. With its wealth of historical and social detail, this book should be on every historical author’s shelf.

You can increase your chances of winning because over at my blog I have a guest post by Williams which is also fascinating reading and I’m giving away a copy there, too.

Richmond Unchained takes an unflinching look at the history of American slavery and Britain’s own in the slave trade and slavery. It places the racism of the time squarely in the middle of a compelling story of a man who lived with the consequences. It’s not possible to read this book and see that not enough has changed.

Richmond’s life is compelling and riveting. As you’ll see in the interview, it took Williams 12 years to complete the book, and his care and attention to detail and chronology shows. From slavery to a position of honor at the coronation of George IV — Richmond is a man who lived an extraordinary life.

About Luke G. Williams

Luke G. Williams, chilling

Luke G. Williams has been a journalist and writer for 16 years. He has worked as a full-time staff writer for uefa.com, sportal.com and euro2000.com, while his freelance work has been published in various outlets including The Guardian, Sunday Express, Snooker Scene, The Independent and 007 Magazine. He has appeared on numerous TV and radio channels, including ITV London, and BBC Radio Five Live. His first book, Masters of the Baize (co-authored with Paul Gadsby) was published in 2005, and was named Book of the Week by The Sunday Times newspaper. He edited the boxing writing anthology Boxiana: Volume 1 (2014) and is the author of Richmond Unchained: The Biography of the World’s First Black Sporting Superstar (2015). Luke lives in London and is the assistant headteacher of a successful secondary school.

About Richmond Unchained

Cover of Richmond Unchained

Today Bill Richmond is largely unknown to the wider public, but he was one of the most significant sportsmen in history and one of the most prominent celebrities of Georgian times. Born into slavery in Staten Island, Richmond won his freedom as a young boy and carved a new life for himself in England as a cabinet maker and then a renowned prizefighter and trainer. His amazing life encompassed encounters and relationships with some of the most prominent men of the age, including Earl Percy, William Hazlitt, Lord Byron, the Prince Regent and Lord Camelford. His fame was such that he fulfilled an official role at the coronation celebrations of King George IV in 1821. The story of Bill Richmond is an incredible tale of personal advancement, as well as the story of a life informed and influenced by a series of turbulent historical events, including the American War of Independence, the fight for black emancipation and Britain’s long-running conflict with Napoleon Bonaparte.

(You see??? You see!!! If you write Regency Romance, you need this book. If you love the history, you should read this book.)

Get Richmond Unchained

Amazon UK | Amazon US | Amberley Books (UK) | B&N | Kobo | Google Play | iBooks

What They’re Saying

Over many years of dogged research, Luke Williams has assembled a wonderful array of new sources to flesh out the fascinating life of a man famed in his own era, but who is only recently being rediscovered by historians. Williams challenges the fanciful Wikipedia myths, and instead reveals the truth to be far more compelling. Richmond was a complex man living in complex times, and has long deserved a biography. It’s heartening, then, that the life of Britain’s first Black sports star is carefully examined by a writer with an obvious passion for his subject.

Greg Jenner, historical consultant CBBC’s Horrible Histories, author A Million Years in a Day: A Curious History of Everyday Life

Richmond Unchained is an accomplished and absorbing study of life and sport in Georgian Britain … A fascinating, and deeply researched, account of one man’s trials and triumphs as he breaches the prizefighting citadel that was Georgian London … A compelling blend of sporting and socio-cultural history, chronicling Richmond’s remarkable journey and eventual recognition as one of prizefighting’s foremost ambassadors … An enthralling odyssey, recounting Richmond’s stellar achievements fought for against the intriguing backdrop of the Georgian prizefighting world … An engrossing biography, and cultural evaluation, that accurately captures the essence of the conflicting qualities of Georgian London’s prizefighting scene.

David Snowdon, author Writing the Prizefight, Winner 2014 Lord Aberdare Prize

This modern biography of Bill Richmond, Britain’s first black boxing superstar, is in my opinion quite simply the most well written, thoroughly researched and historically accurate work of its kind ever produced. Not only does the author touch upon and explore many of the known and lesser known mysteries and themes of Richmond’s life, he also manages to successfully explain the often complicated background history of his times, and does so in a highly readable and fascinating way. If you are interested in sport, or in British social history, or in reading about an icon and trailblazer for black athletes of today, then this book should be top of your current reading list. I think this book is also going to be an inspiration for many people for a long time into the future, and all credit to the author for bringing this boxing legend out of his current state of relative obscurity and putting him back in his rightful place as the founding father of black boxing, not just in Britain, but also the world.

Alex Joanides, boxing historian, Romevillemedia.co.uk, editor Memoirs of the Life of Daniel Mendoza (2011 edition)

The Interview!

First, thank you so much, Luke, for agreeing to be interviewed! I loved your book and I’m really excited to have you here!

Q: In your book, you mentioned that your father gave you a copy of the book Black Ajax. Was that an out-of-the-blue gift or did your father have some specific reason to believe you’d enjoy that book?

A: I was incredibly lucky growing up to have a mother and father who really encouraged me to read and develop a love of books. My dad was obsessed with books, in fact I can’t remember a single birthday or Christmas gift from him that wasn’t a book! His other obsessions were betting on horse races (not large amounts I hasten to add), Buddhism and pretty much all sports. An eclectic set of interests! Boxing was one of the many sports we watched together and I developed a real interest in the sport’s rich history, particularly its importance socially and culturally. My dad knew this and when he saw a copy of Black Ajax in a bookshop in central London he guessed I would enjoy it and, boy, was he right! It’s a wonderful novel.

Q: I’ve read a lot of books about historical periods or events that are pretty thin on crucial information like dates. Your book almost always uses specific dates with month, day and year (or for you folks over the pond, day, month, year) and you note when documentation is unclear as to date. Naturally that involves some painstaking documentation and note taking. Did you have a system? How did you keep all the chronologies straight?

A: I’m so glad you picked up on this and asked about it. I realised when researching the book that a lot of information already out there about Bill Richmond was either wrong, exaggerated or had been misinterpreted. Mainly this is because boxing historians who have written about him have solely relied on Boxiana by Pierce Egan, and books such as Miles’ Pugilistica and Fleischer’s Black Dynamite which simply aren’t written with any historical rigour whatsoever or reference to any primary sources. One of my principal aims with Richmond Unchained was to assemble the most complete factual account of Bill’s life that I could so that the real facts were on record somewhere. That meant returning to birth records, marriage records, tax records etc and original newspaper reports, rather than later recycled accounts. This depth of research explains why the book took about 12 years to complete from conception to publication! I used a pretty straightforward system – I filed all my paper research by month and year in chronologically ordered folders and, once my research graduated online as the Internet took off, I did the same thing with scans of material I assembled. It was a huge undertaking, but I couldn’t even start writing the book until this volume of research had been completed.

Q: When I was looking around the web I came across your author photo. After careful examination, on the left side of the picture by your shoulder, there is clearly an aquatic creature in attack mode. Is that a Great White or the Loch Ness Monster? Which would you rather face in a duel? In a battle to the death between the shark and Nessie, who wins and why?

A: LOL! You know what? I can resolve the mystery for you of this sea creature. That mysterious shadow is actually a result of my incredibly poor photo-shopping skills. This photo was taken by the pool of a hotel in Los Angeles and originally the shadow was a female swimmer who had a rather pained expression on her face so I tried to remove her! As for Nessie versus a shark, I see Nessie as an elusive Bill Richmond type, whereas the shark would just plough forward relentlessly like Jack Holmes or Tom Shelton. Nessie / Richmond would use superior stealth and movement to tire the shark out and win with ease.

Q: Set aside for the moment the need to draw conclusions only from documented facts. Given everything you’ve read, what do you believe happened in the first Cribbs vs. Molineaux fight. How much of what happened do you think Richmond probably anticipated or was prepared for?

A: That’s the $64,000 question, isn’t it? In a nutshell, I believe that Molineaux was cheated, although I don’t think we can ever prove this beyond doubt. I think there was a ‘long count’ of some sort at some stage as well as a ring invasion, which helped tip the balance in Cribb’s favour. I think that in the back of his mind, and based on his experiences in the ring and growing up in England, Richmond knew that such shenanigans were possible. However optimistically, and perhaps naively, I think he believed these obstacles could be overcome. I know one thing for sure – if time travel is ever invented the first place I am going is Copthall Common on 18 December 1810 because I am desperate to know what actually happened!

Q: My guess is you might be a fan of boxing in general. If Richmond were transported from the past to now, what you do think he’d make of the current state of boxing? Which fighters might he admire? My impression from reading your book was that Richmond was something of a technical innovator in the sport. Do you agree?

A: Yes, I’m still a fan of boxing. I’ll admit that I’ve had my moments where I have fallen out of love with the sport, but I always seem to return to it. I don’t think Bill would be particularly impressed with the state of boxing today. I think he would admire Floyd Mayweather on a technical level, but not on a personal level, as he is pretty far removed from the concept of the gentleman pugilist epitomised by Bill Richmond! Bernard Hopkins would also win Bill’s admiration for the way that, like Bill, he has led an abstemious and disciplined existence, allowing him to box well beyond an age which conventional wisdom holds is advisable. I do believe that Richmond was something of a pugilistic innovator as well as one of the earliest and most effective trainers and fight promoters. Bill probably didn’t originate the concept of ‘boxing on the retreat’, but certainly it was an art that he perfected and succeeded in winning praise for, putting paid to accusations that such a style was ‘unmanly’.

Q: I was intrigued by the photo of you and Earl George Percy unveiling the long overdue tribute to Bill Richmond. Has the connection between the Percy family and Richmond been family lore for them (if you know) or was it something they learned of later? If there were to be a more substantial memorial of Richmond, what form would you like to see that take?

A: It was incredibly gracious and generous of George to unveil the tribute. I managed to meet him through a mutual friend who has a great interest in Georgian boxing. George told me that he only found out about the connection between his family and Bill a couple of years ago, so I think it was a piece of family folklore that had become somewhat lost in the mists of time. Once he found out, he was intrigued and looked through the archives at his family residence Alnwick for more information, but there is very little there. When my friend informed George about my book he was very excited and intrigued and kindly agreed to act as guest of honour at our event. I’m really pleased with the memorial and the kindness displayed by Shepherd Neame brewery in arranging it after I suggested the idea to them. If another memorial was to appear to Bill I would love it to be a statue on a plinth in Trafalgar Square – close to where his Horse and Dolphin pub once stood. (Hey, I can dream, right?)

Q: I would love to see a movie or BBC production about Richmond. Idris Elba could play Richmond. Who would you cast in such a production?

A: This is one my dream scenarios as I think that Bill’s life story is crying out for a multi-part BBC or HBO mini-series! I’m a huge admirer of Idris Elba, ever since I first saw him in The Wire (incidentally the best TV series ever made IMO), however he doesn’t quite fit my mental image of Bill, largely because of his build, which is larger and more imposing than Bill’s. If Idris was a little younger then I think he’d be a great Tom Molineaux. I’d cast Chiwetel Ejiofor as Bill – I think he is one of the best actors working today. His build is right for Bill, and he would be equally comfortable with the urbane and erudite side of Bill’s personality, as well as the physical challenges. He is such a versatile performer, who possesses such depth of dramatic power. Funnily enough, I went to high school with Chiwetel and had the pleasure of acting with him in a several productions. If we needed a younger actor as Bill, perhaps to play him in his late teens or twenties, then Michael B. Jordan, based on the charming mixture of vulnerability and strength he displayed in the brilliant Friday Night Lights, would be a good choice, if he could master the English accent which I’m sure Bill possessed.

Q: What’s next for you?

A: Fatherhood! My wife is expecting our first child any week now, which is incredibly thrilling. In terms of my writing and research, I want to continue to spread the word about Bill Richmond. I’ve lived with his story for so long and have such admiration for him that I want as many people as possible to know about his life. I would love it if my book resulted in more information about Bill emerging, particularly in terms of tracing any descendants. If that’s the case then I would love to produce a revised edition of Richmond Unchained in the future. I’d also like to have an expanded edition published which includes all the references and sources which couldn’t fit in with the page restrictions I was working with.

(I’ve made a start posting these on my blog at billrichmond.blogspot.co.uk). I have a couple of other ideas for books I’d like to write, which would also connect with Georgian boxing, however the process of research is so painstaking that I think any further book is a long way off. Above all, I’m looking forward to spending time with my wonderful wife and baby, and continuing in my role as assistant head-teacher of a fantastic school in south London where I have now worked for 11 years.

The Giveaway

I’m giving a copy of the book to one commenter. It’s out in digital format now, print forthcoming. So I can send you your choice. If you’re in the US, it should be pretty easy. If you’re outside the US, it’s a little trickier, but we’ll work it out. I might not be able to get you a digital copy.

Rules: Must be 18 to enter. Void where prohibited. No purchase necessary. Prize will be awarded to an alternate winner if the winner does not respond to notifications from me.

To enter, leave a comment to this blog post. If you have questions for Luke, ask away! It would be awesome if you comment about the post, but telling me what color breeches you think Richmond should be wearing is fine. (It’s yellow on the book cover.) Leave your comment by 11:59:59 PM Eastern Time Thursday September 10, 2015.

GO.