No release date yet for The Magnificent Marquess! Possibly end of this month? Or early May? In the meantime, I’d like to share a recent, new-to-me discovery.

Do you listen to the radio all day or play music on your computer while you work? In the Regency, was there any way to listen to music that wasn’t being performed on live instruments? Actually, there was. You might have received the gift of a music box from your forever-love, or at least have been wealthy enough to own one. Or your parents’ parlour might sport an automaton of singing birds!

I was inspired to explore this topic by my recent visit to Phoenix, Arizona, where we visited the very impressive Musical Instrument Museum (affectionately known as “the MIM”).  The international collection there ranges from some very early and exotic instruments to items as recent as the broken guitar Adam Levine threw into the air during a Maroon Five concert. Many of the instruments are gorgeously decorated works of art beyond their artistic function. But I digress.

The international collection there ranges from some very early and exotic instruments to items as recent as the broken guitar Adam Levine threw into the air during a Maroon Five concert. Many of the instruments are gorgeously decorated works of art beyond their artistic function. But I digress.

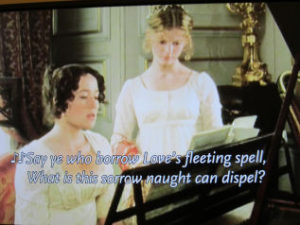

When I’m in museums I admit I tend to focus on anything that is from our period (obsessed much?). At the MIM I thoroughly enjoyed seeing guitars and pianofortes that were played by upper class women and made during the Regency. I was delighted to discover a video clip from Pride & Prejudice used to illustrate the significant social role of such musical performance.  But I already knew about those things. My favorite discovery was some early music boxes in the “mechanical music” room. I had never thought about when those first became available. Did you know that musical snuff boxes were the forerunners of the modern music box?

But I already knew about those things. My favorite discovery was some early music boxes in the “mechanical music” room. I had never thought about when those first became available. Did you know that musical snuff boxes were the forerunners of the modern music box?

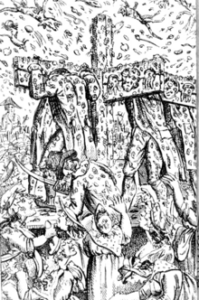

As with most inventions, earlier developments led to a needed breakthrough in technology. For music boxes, those steps included the 14th or 15th century creation of mechanisms for playing carillons in bell towers,  and the realization by German clockmakers that small bells and the rotating cylinder could be combined with clockworks to produce chiming or musical clocks. In the17th century the first fully automated musical clock was created in Germany, and the first “repeater” pocket watch was created in England.

and the realization by German clockmakers that small bells and the rotating cylinder could be combined with clockworks to produce chiming or musical clocks. In the17th century the first fully automated musical clock was created in Germany, and the first “repeater” pocket watch was created in England.

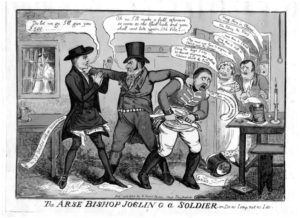

I’m not going to give the whole history with dates and names in this blogpost (especially since sources don’t all agree), but in the 18th century watches and snuffboxes were being made that played tunes using a tiny pinned cylinder or disc and bells.

The generally accepted big change happened in 1796 when Swiss watchmaker Antoine Favre-Salomon (1734–1820) — some sources name him as Louis Favre –replaced the tiny bells with a small, resonating steel “comb” tuned by varying the lengths of the “teeth”. This snuff-box music box showing the working cylinder and comb is in the MIM in Phoenix.

Favre’s invention not only saved space but also allowed more complex sounds. In 1800 another Swiss watchmaker, Isaac Daniel Piguet, used a pinned disc with radially arranged steel teeth. Watchmakers were the first to produce music boxes. But by 1811 the first specialized factory for making music boxes was established in Saint-Croix, Switzerland, and by 1815, 10% of Swiss exports were music boxes. A new fad for the wealthy was born!

There’s a story that Beethoven was so charmed by a music box that he composed a piece especially for the music box maker. Improvements soon included adding more teeth to the comb, methods to shift the cylinder or disc position to play more than one tune, and experimenting with different types of wood to improve music box resonance. Here is a picture from the MIM of a piano-shaped music box c. 1835 that was also a lady’s sewing box.  Music boxes became more and more elaborate over the course of the 19th century, and also less costly. The music box industry in Europe and America eventually employed more than 100,000 people. The invention of the player piano and then the phonograph put most of the makers out of business by the early 20th century.

Music boxes became more and more elaborate over the course of the 19th century, and also less costly. The music box industry in Europe and America eventually employed more than 100,000 people. The invention of the player piano and then the phonograph put most of the makers out of business by the early 20th century.

Let me not forget the singing birds! Those have a long history, too, but the first mechanical birds that “sang” are generally credited to the Jaquet-Droz brothers, clock and automaton makers from La Chaux-de-Fonds, in 1780. The same sort of mechanism as music boxes provided their sounds. Singing bird automatons were a fad for the parents or grandparents of our Regency characters, so there is no reason why a set might not still be lurking in a parlour, or parked in the attics of the family home. Automatons could be the topic of another entire post, a separate fascinating rabbit hole!

Do you love music boxes? Do you own any, or did you as a child? Did you know they first gained popularity during the Regency? I didn’t, but many thanks to the MIM in Phoenix for pointing me to that discovery!